Art Curator’s Deep Dive: Pandora is out of her (storage) box!

Last week, the University Art Collection rehung Pandora, a large painting in tempera by John Dickson Batten. Presented to Reading’s University College (a precursor to the University of Reading) in 1918, this painting was one of the first artworks in our collection. In this blog, Dr Hannah Lyons, our Curator of the University Art Collection, sheds further light on this multifaceted painting.

Every Monday, the University of Reading’s Museums and Special Collections Service (UMASCS) is closed to visitors. This lets us to do important collections care work including conservation assessments, light cleaning, and often, rehanging our artworks. Last week, with thanks to our Collections Care Manager and a team of helpers, we took the opportunity to redisplay one of the largest and oldest paintings in our Art Collection: Pandora.

The painting has been in storage since April 2023, but, after a year of much needed rest, Pandora is out of her box and back on display in the redeveloped Staircase Hall. Looking resplendent against the freshly-painted green walls, I took the opportunity to delve a little deeper into the novel ways in which the artist approached the myth of Pandora.

Painting in Tempera

In 1913, the British artist, John Dickson Batten submitted a large painting in tempera to the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) summer exhibition at Burlington House, Piccadilly. The RA was the most prestigious venue in London for the exhibition of contemporary art, and Batten was no doubt delighted that his painting had been accepted by the all-male committee, who decided that it should be hung in the ‘Water Colour Room’, as seen in this RA catalogue.

Batten’s choice of subject-matter was the Greek myth of Pandora. While there are various and often contradictory stories, most agree that Pandora (‘Pan-dora’ meaning ‘all-gifted’) was the first woman fashioned out of clay and sent to earth by the gods. Each of the Olympian gods had given Pandora a gift – beauty, curiosity and charm – all of which were destined to wreak havoc among men. Pandora’s curiosity led her to open the jar (mistranslated later as ‘box’) she had been gifted by Zeus, which contained, as well as hope, all the evils since visited upon the human race.

It seems likely that the ‘Water Colour Room’ was chosen over the numerous ‘Oil Painting’ rooms as the most suitable space for Pandora because of the artist’s chosen medium; Batten chose to paint Pandora in tempera, a permanent, fast-drying painting medium, consisting of coloured pigments with a water-soluble binder medium like egg-yolk. Painting in tempera wasn’t an unusual choice for the artist, who had been experimenting with this historic medium since the 1890s. In 1901, both John Batten and his wife Mary Batten, a gilder, were founding members of The Society of Painters in Tempera. The society championed the revival of tempera painting, which had been used since Antiquity but was most commonly found in early 15th century Italian paintings.

If we look closely at Pandora, particularly at the deep, rich hues of blue and orange on the right-hand side of the painting, we can see how Batten has mastered the technique to great effect. Indeed, one critic reviewing the Royal Academy exhibition in 1913 remarked on ‘the fine decorative quality’ of the painting – a comment that I think many of our visitors would agree with!

Reading Pandora

The same critic praised John Dickson Batten’s ‘ambition’ in conceiving and executing such a painting. No doubt he admired Batten’s use of the tempera technique, and probably the scale of the work, which would have made a fine spectacle on the Academy walls at 128cm high and 168cm wide. He might also have been impressed with Batten’s choice of subject-matter; rather than depicting Pandora and her infamous box, Batten chose to highlight the moment that Pandora was first formed by the Greek gods from fire and clay. But how did Batten tackle this less familiar part of the myth?

To the left of the painting, we can see Hephaistos, god of fire and patron of craftsmen, staring across the canvas at Pandora, his most recent work of art. Hephaistos rests his foot on an large anvil and in one hand, clutches one of the tools that he used to make Pandora. Behind him, one can almost hear the thumping and clanging of his forge, where three animated male figures continue to grind, chisel and hack.

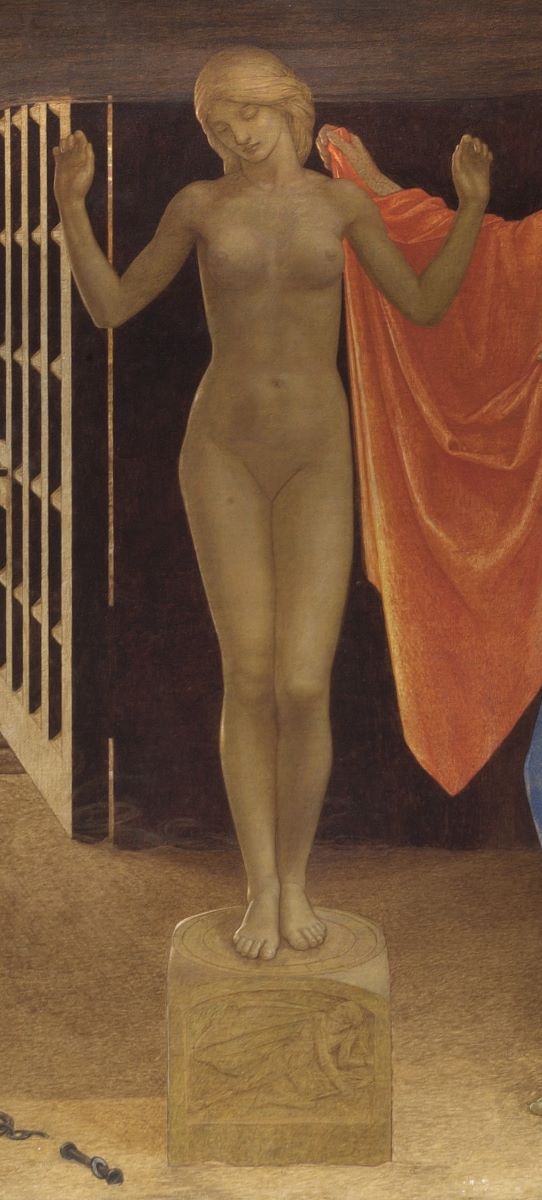

If we follow Hephaistos’s gaze across to the opposite side of the artwork we meet Athena, goddess of arts, wisdom and warfare. Athena reaches out to clothe Pandora in a fabric of luminous orange (as seen above). The goddesses’ head – in profile to the right – strikes me as distinctly Pre-Raphaelite in style; evoking paintings that artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais made of their wives, lovers and muses. Batten worked in the studio of Holman Hunt and, as student at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, would have been familiar with the work of this earlier, influential generation of British artists.

However when stood in front of this work, it is Pandora’s naked body, displayed on a plinth like a classical sculpture in the centre of the composition, that draws and holds our attention. Here Batten has depicted Pandora looking down, her arms raised for the viewer to fully take in her nubile body. Is she aware that we – the visitor in the Staircase Hall in 2024, or the visitor to the RA summer exhibition in 1913 – are watching her? Does she feel the intense gaze of her maker, Hephaistos, across the canvas? The only figure that engages directly with us is one of Athena’s female followers, her finger raised to her lip, her glance knowing. Does she know that this first woman, this ‘beautiful mischief’, will open the forbidden box and unleash peril?

Pandora’s Box

Though images of Pandora began to appear on Greek pottery as early as the 5th century, she became a popular subject for European painters, who often saw her as a pagan counterpart to the fallen Eve. The Irish artist, James Barry (1741-1806), chose to create a large-scale oil painting of The Birth of Pandora, now in Manchester Art Gallery (c.1791-1804). William Etty (1787-1849) approached the subject of Pandora Crowned by the Seasons in two paintings now in Birmingham Museums Trust (1823-24) and Leeds Art Gallery (1824). Henry Howard’s interpretation, commissioned for the ceiling in Sir John Soane’s Museum (1834) depicts a scene a little closer to Batten’s chosen narrative; Pandora is dressed by Athena and the Graces, though her ‘fatal vase’ is clearly included in this composition.

Members of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, of course, took to the myth with gusto. Using Jane Morris as his model, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s recognisable painting of Pandora (1869) was hailed by Sotheby’s in 2014 as one of ‘the most important Pre-Raphaelite paintings’ (though this may have been tied to the £7 million price tag!). This work would likely have been known to Batten, for it was exhibited in London several times during his lifetime. But though Rossetti’s Pandora has been described as a ‘dark, brooding beauty’, ‘a full-blown, wild-eyed femme fatale’ and ‘frighteningly powerful’, the same can’t be said of Batten’s interpretation. To me, Batten depicts Pandora as an innocent, subservient, vulnerable young woman. She is not a portrait of a familiar muse (as Rossetti’s was), but is a statuesque symbol of idealised, late-Victorian femininity. Batten’s Pandora has not yet given into the temptation of opening her infamous box.

More time and research is clearly needed to fully unpick Batten’s painting, but I would love to hear what you think in the comments below. You can view her in-person on display in Staircase Hall, or visit our online exhibition here.