Portraiture and the Art Collection

Cerys Cartwright, a third-year art student on placement with the University Art Collection explores portraiture in the University Art Collection

I have been fortunate enough to spend several weeks working with the University Art Collections, learning and experiencing the collection first-hand. I started my placement working on the inventory of the Art Collection Study Room and had the opportunity to view a range of art works, from the wonderful Betts Collection, including Walter Richard Sickert, to the beautiful pieces by Eric Stanford, and Allen Seaby, amongst others. Of the many genres I saw, portraiture was among my favourites. It is something I personally practice; having the chance to capture a snapshot of some of my favourite people connects me closer to my art.

Portraiture is one of the oldest art forms to exist, dating back over 5000 years, and was hugely popular with the Ancient Egyptians. Google Arts and Culture defines it as a “painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person, in which the face and its expressions are predominant, with intent to display the likeness, personality, and even the mood of the person.” Portraits have been used to show the power, importance, virtue, beauty, wealth, taste, learning and other qualities of their sitters. Artists have often portrayed their subjects in a flattering way, almost like a modern day photoshop and filters.

Throughout art history up to the present day, there has been a strong tradition of patronage and commissioning in art. These patrons acted as sponsors and would fund an artist’s expenses. To keep these patrons and buyers happy, artists were inclined to show their sitters (often their patrons/buyers and their families) in the best light. A fitting example of this traditional, commission-based portraiture is a grand portrait of Alfred Palmer, painted by Arthur Stockdale Cope, situated outside the Art Collections Study Room. Cope’s sitters were often high-ranking members of society; Alfred Palmer was no exception.

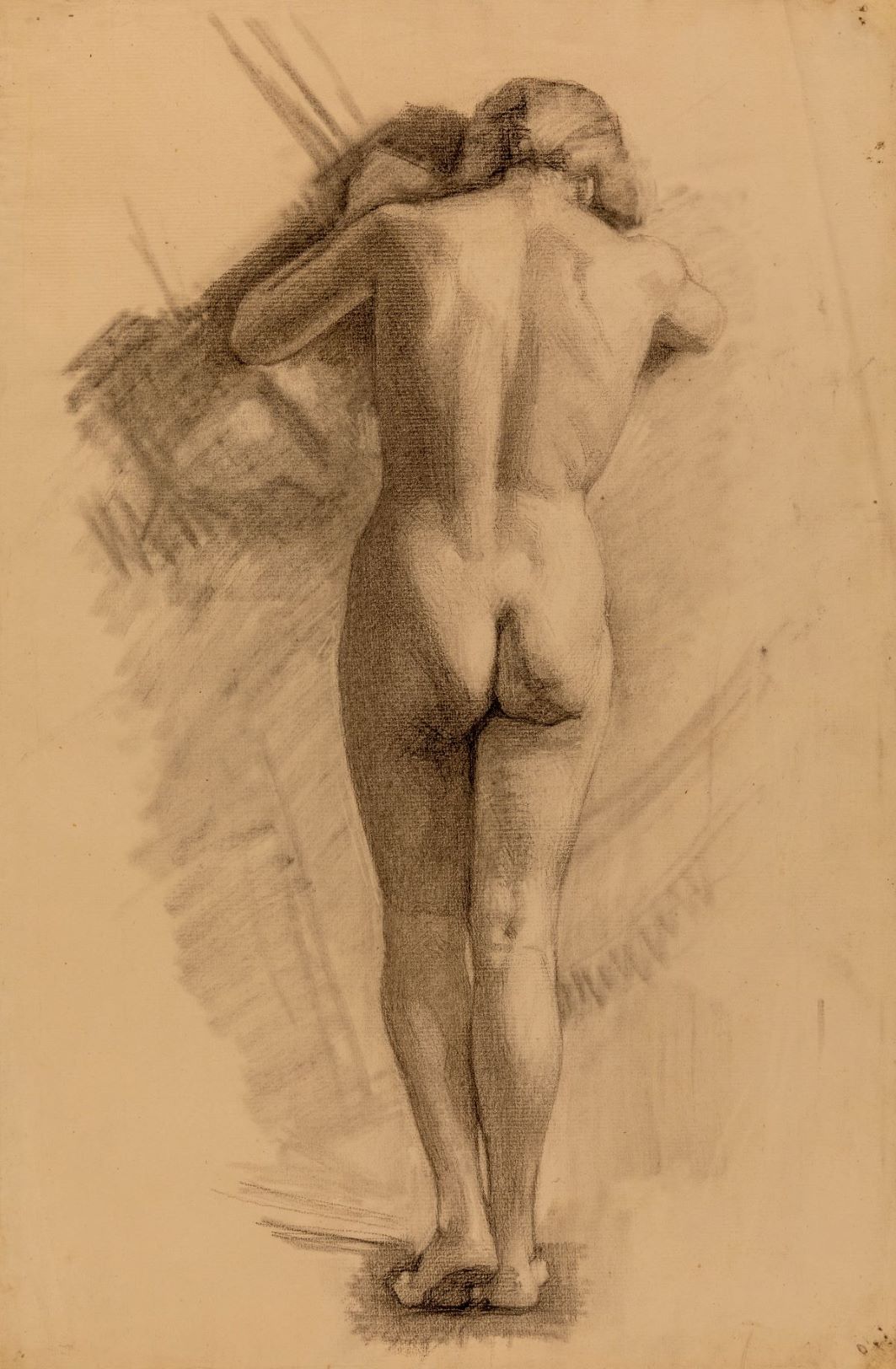

A direct contrast to this is portraiture in life drawing, which focuses on capturing a realistic portrayal of the model. Practicing drawing from life was considered the pinnacle of learning how to draw and eventually became an avenue into realism. At many art schools, life drawing classes were initially limited to male students. Men in the art industry felt it was inappropriate for women to see nude, or even partially covered, models due to their “delicate womanly nature”.

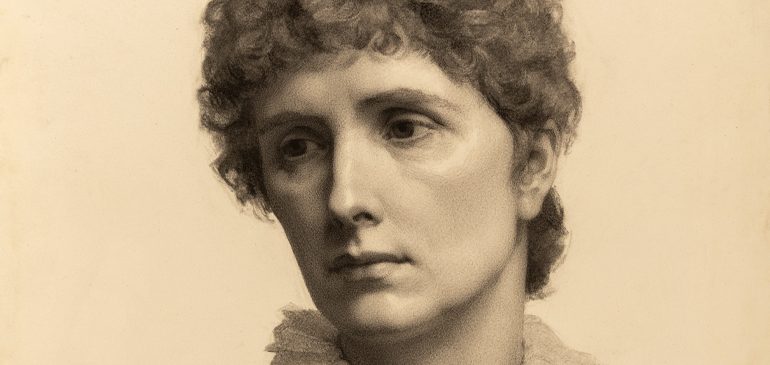

Female students at the Royal Academy from the 1860s-1880s were limited to “Ladies Drawing”, which often focused on portraiture. Minnie Jane Hardman who was a promising student at the Royal Academy Schools between 1883-1889, faced these restrictions. This is evident in the many works by Hardman in the University Art Collection. While there are many examples of her antique, anatomical and life drawings, these rarely include nude studies. Those that do appear are notable for the lower quality of paper used, indicating that she looked for classes outside of the Royal Academy. This is evident in the two drawings below, with the grain of the paper visible in the shading seen the nude drawing.

In my opinion, the life-like portrayal in Hardman’s portraits is extraordinary in execution. The bust length portrait above is almost photographic. I could only imagine how long this may have taken her to draw and the duration of time the model would have had to sit still for. I find it almost impossible to draw siblings, without a bit of bribing.

In contrast to the days of Minnie Jane Hardman, life drawing classes are not as prominent as they once were in university settings. For me, they are a non-compulsory class after seminars and lectures. Traditional life drawing faded out of fashion with the introduction of abstraction. However, portraiture was still a central art form within this new type of art.

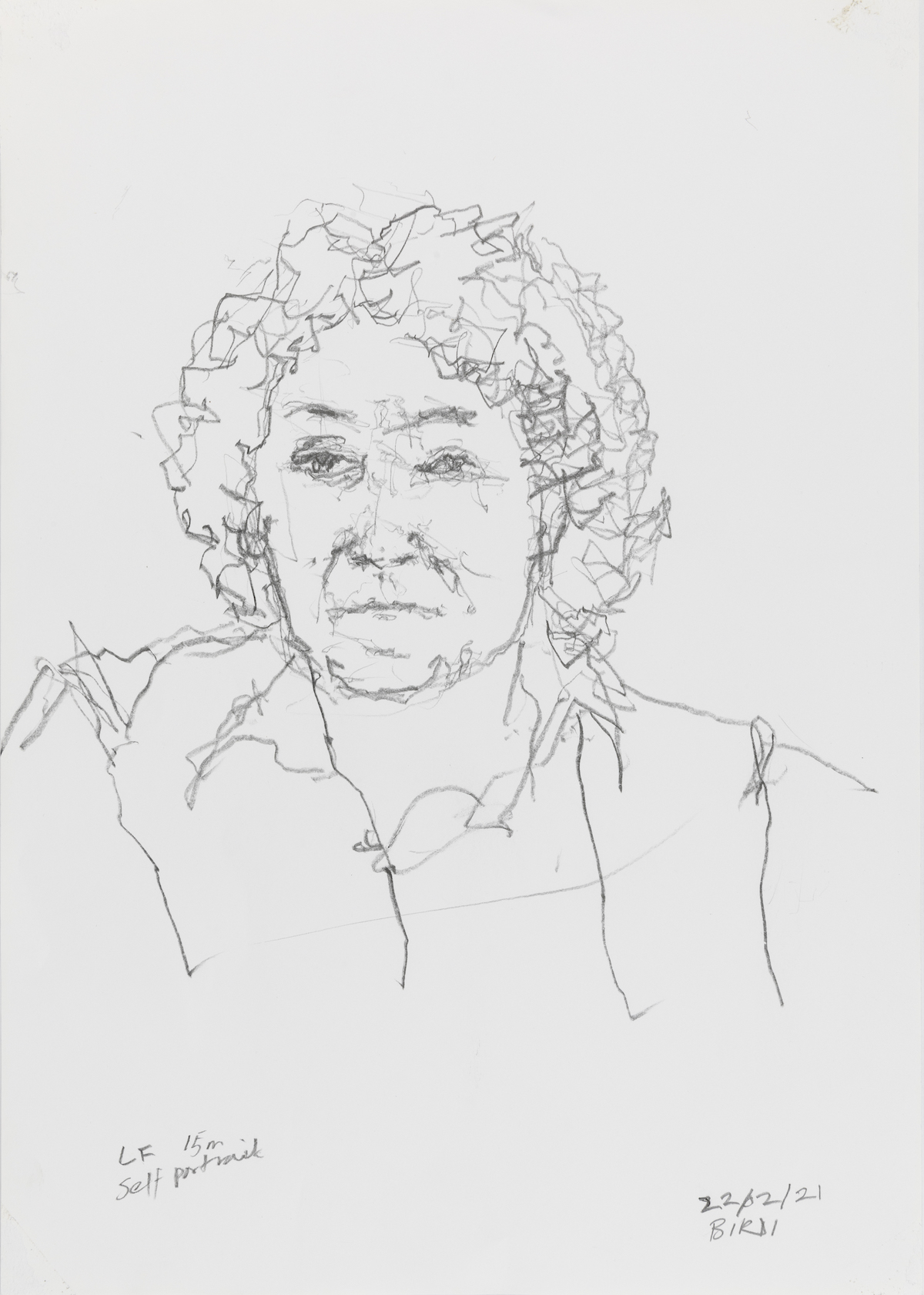

Abstraction threw open the doors to what was possible in art. Today we can see artists like Saranjit Birdi, whose artworks include life drawing, portraiture, drawing, and performance. Birdi’s drawing methods include foot drawings, where he takes the non-traditional route of sketching with his feet, creating some interesting, flowing line work. Personally, I am impressed with the likeness and control of the pencil given it was not completed by hand and how quickly he tends to capture this.

Above is an image of a 15-minute self-portrait drawn with Birdi’s left-foot which he completed during Zoom workshop with the University of Reading’s Institute of Education. This was created as part of his Drawing Diversity Artist Residency. Perhaps this portrait is the latest in the long line of commissioning and patronage?

There are many wonderful portraits to explore in the University Art Collection and I recommend seeing them in person.

Here are some links and information to get your journey started!

- If you wish to explore artists like these in the art collection, please visit Collections A-Z . You can also access artworks in the collection through Enterprise and ArtUK.

- Follow us on social media: Instagram or Twitter!