The Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology at the University of Reading is an integral part of Reading’s Department of Classics and known widely as the fourth largest collection of Greek ceramics in Britain. Yet it displays artefacts from other Mediterranean civilizations. At least 50% of its Cypriot holdings, which number approximately 100 artefacts, are liberally distributed throughout the Museum in thematic displays on myth & religion, household, technique & decoration, etc.

The Cypriot collection displayed at the Ure Museum consists of a number of bequests, donations and loans[1]. It includes artefacts on loan from the Reading Museum as well as those in the ownership of the University, all of which have been published recently in our 2015 Corpus of Cypriote Antiquities, volume 23. Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology. Yet our Cypriot collection, which lends itself more to educational than traditional research purposes remains relatively unused both because Cyprus is little ‘studied’ by our visiting pupils at Key Stages 2 and 3 (where Greeks, Egyptians and Romans take centre stage as dictated by the national curriculum). Our decision to forefront Cyprus in our utilisation of new—especially 3D—technologies is in part motivated by an effort to make better use of the Cypriot holdings.

Our educational programme is closely linked to pedagogies of active and experiential learning, which sees hands-on engagement with the object of study as a key to personal meaning-making and long-term retention of ideas. Object-based learning has proven to facilitate the understanding of a subject, the development of academic and transferable skills such as teamwork and communication, lateral thinking, practical observation and drawing skills.

Such pedagogies have proven to have a long-lasting effect on retention skills and thus relate to memory, probably due to their multi-sensory approach[2]. Object-based learning can also trigger innovative dissertation topics[3] when applied to archaeology and related studies[4]: the Ure collection in the last decades has provided subject material for undergraduate student dissertations at all degree levels in Typography, Museum Studies, Ancient History, Classical Studies, and Art History, as well as Archaeology. Artefacts, although concrete, represent a vast continuum of abstract ideas and inter-related realities that are to be discovered by children[5].

As John Hennigar Shuh[6] has pointed out, the value of object-based learning methods can be summarised with three premises: first, objects are not age specific and can thus reach across diverse groups of people. Artefacts can be used by people of any age, while the methods of questioning and conclusions drawn will vary. This also applies to people with differing abilities and is a distinct benefit in today’s world in which literacy and numeracy skills are traditionally favoured[7]. Objects can be used to draw a group together and encourage conversations. Secondly, one can use objects to look at the lives of ordinary people. The display of the collection at the Ure Museum allows learners to analyse objects relating to people, events and traditions rooted in antiquity. Thirdly, objects give us the chance to develop our capacities for careful, critical observation of our world: introducing new learners to real objects, real evidence of the world around them and of the past, encourages them to think beyond their everyday experience.

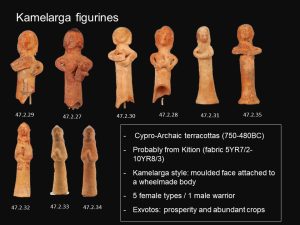

- Kamelarga figurines at the Ure Museum

The focus of our project is a group of nine figurines formerly in the possession of Gore Skipworth, who claimed they had come from “old tombs in Cyprus”. These mixed technique terracottas, which date to the Cypro-Archaic period (750-480 BC) are probably from Kition, with a fabric that ranges from greyish-pink to reddish-orange. They are of the Kamelarga style, which is characterised by a moulded face attached to a wheelmade body: we have five female types and one male warrior. These figurines were found in sanctuaries and tombs, and have been traditionally interpreted as ex-votos to ensure prosperity and abundant crops[8].

As part of our educational programme, we designed a workshop to delve into the function and symbolic meaning of these figurines, implementing new techniques and methodologies to expand our object-based learning pedagogies. Through photogrammetry we created 3D models of the artefacts that virtually re-created them. We then printed some of the models which helped our audiences to engage with the figurines more deeply than the artefacts themselves. This is not only because visitors are less bashful about handling them but also because the 3D prints encourage their perception of the multiplicity of such figurines that were regularly encountered in the cultic context in which they were found. The procedure of 3D printing the figurines proved to be useful means of engaging with materiality issues, such as scale, colour, texture, weight and iconography.

For more on 3D printing experimentation, please click here

[1] Smith 2015 :vii in Pickup, Bergeron and Webb 2015

[2] Romanek and Lynch 2008: 284. Biggs 2003: 80.

[3] Chatterjee 2010: 179-81. Chatterjee 2008: 215-223. Chatterjee and Hannan 2015: 1-8. Durbin et alli 1991: 7.

[4] Beazley 1989: 98-102.

[5] Paris 2002: 10.

[6] Shuh 1982: 8-15.

[7] Kennedy 2016: 2.

[8] Pickup 2015:21; Leriou 2017.