The Well-tempered lyre: Music education in ancient Greece

Music was an integral part of Greek life, in the spheres of religion, competition and warfare, as well as for relaxation. It also marked the most important moments of life, at births, weddings and funerals. Ancient Greeks therefore educated their children, both girls and boys, in music from a young age. Even in infancy, children played with instruments and learned through songs. Later on, children learned to play the lyre, either in formal setting or at home, and some went on to become professional musicians. This online exhibition explores this musical education through material culture—instruments and images—from across the Mediterranean.

Cypriote Bell

Child graves often included bells, simple instruments used in singsong games and as toys. This bell was found in a tomb in Cyprus. The inclusion of bells and other simple instruments in burials suggests music was important both in life and in death. Perhaps music helped to soothe and entertain these children in the afterlife. The simplicity of these instruments made them easy for children to use and added an educational element to their games through the self-learning of musical rhythm. Our terracotta bells, from Cyprus and Boeotia, function essentially the same way, with suspended clay clappers that produce sound when shaken. Like most ceramics, however, they show differences in shape and decoration. These differences are explained by regional variation. Bells were also used as gifts to the gods. On Sparta’s akropolis, for example, a large number of bronze bells were found with inscriptions dedicated to Athena.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

Boeotian Rattle

Rattles are a class of percussion instrument similar to bells. It is likely that adults used these rattles to soothe babies and very young children. This terracotta rattle from Boeotia still contains a pebble that rattles when shaken. Rattles could be decorated with figural scenes, but some were shaped like animals. Pig-shaped rattles, such as one in the J. Paul Getty Museum, recall animals sacrificed to Greek deities, especially Persephone and her mother Demeter, in return for protection of children. Rattles, like bells, may have comforted children on their journey to the Underworld or as a way to ward off evil spirits.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

Figurines with cymbals

Cymbals are another percussive instrument that taught children about music at a very young age through the medium of songs and games. It is possible that some of the Ure’s Kamelarga figurines from Cyprus hold cymbals. Do these figurines represent children or adults, women or men, or even divine figures? Their forms are so abstract that we cannot be sure. The Titan goddess Rhea appointed mythic spirits called Kuretes to guard her baby, Zeus, from his father Kronos. Kronos wanted to eat Zeus in order to prevent him from overthrowing him, as had been prophesied. The Kuretes beat their shields together to mask the sound of his crying, according to the Roman poet Ovid. Perhaps this myth evolved from the association of cymbals with children: cymbals and figurines holding them have been found in Greek as well as Cypriote graves.

You can view some of our figurines in 3D on Sketchfab.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

Hammering blacksmiths

Music also helped children learn the principles of mathematics, another key area of ancient Greek education. The philosopher Pythagoras realised the importance of harmonics and how music related to mathematics when he heard blacksmiths hammering in their forge, so the legend goes. For Pythagoras and his followers, music was a mathematical expression of the cosmic order. The frontispiece to the first volume of Athanasius Kircher’s Musurgia Universalis (1650), engraved by Baronius of Rome after a drawing by John Paul Schor, alludes to this myth. It shows the blacksmiths hammering in a cave, while Pythagoras points to them with a stick. The legacy of ancient Greek music—and its education–have been an important part of western music and its development and therefore remain part of our everyday lives.

You can find a copy of this text in the University of Reading’s Special Collections.

Credit line - Glasgow University Library via Internet Archive

Replica lyre

The chelys (tortoise-shell) lyre was often used for teaching children music because it was lightweight, affordable and relatively simple to learn, compared to other instruments like the aulos and kithara. The Homeric Hymn to Hermes tells the story of how the first lyre was made by Hermes. He scooped out the marrow out of a mountain tortoise, fixed stalks of reed to the shell and stretched ox hide over it. Then, he attached two horns and a cross piece between them and added strings. The Ure Museum lyre is a modern replica, constructed in a similar manner but with wood instead of horns, as seems to have been the norm (we would probably have been told of by an ancient teacher for our poor attempt at stringing the strings). Few ancient Greek lyres survive because they were made of perishable materials but images of lyres, for example on our Paestan krater, help us to reconstruct them.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

Music lessons

Pedagogues—enslaved people in charge of their owner’s children—taught musical skills to their young charges at home. This Boeotian cup depicts seated boys playing lyres in the presence of standing men. Perhaps they are pedagogues who supervise them. The man leaning on a stick may represent a pedagogue or perhaps a more formal music teacher. As early as the 6th century BC some Athenian boys between the ages of 13-16 were taught in schools of music to play the lyre and to sing, accompanied by the teacher. But just what kind of music was best to teach children was fiercely debated by philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

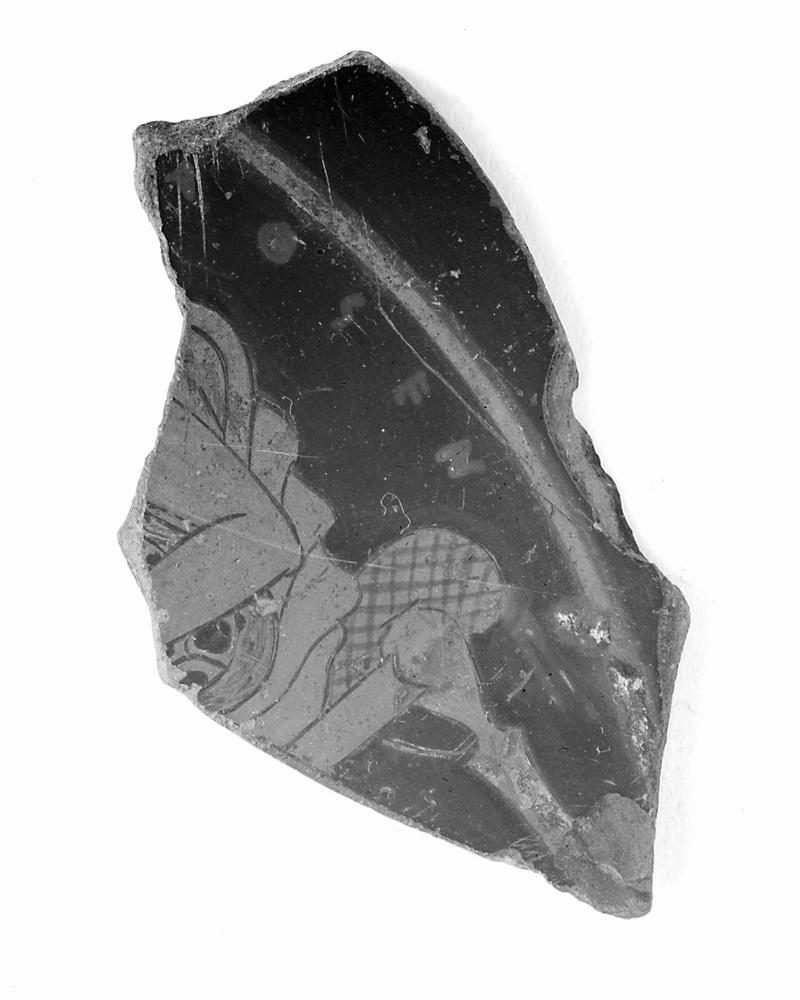

Lyre player

This cup fragment preserves part of a similar scene to the Boeotian cup. A boy plays the lyre. We can just about see part of his left arm, a fold of his robe, the top of the cushioned stool on which he sits, and the tortoiseshell pattern of the lyre he plays. The fragment also preserves the last part of the signature of the Athenian artist, Douris, who painted many such ‘school scenes’.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

Singing lessons

The outside of this Attic cup in Berlin was decorated by Douris, the same artist who signed our fragment. Here boys play the lyre but also sing with musical accompaniment. At the top centre, an older man holds a scroll for a youth to sing. Perhaps in more advanced lesson the boy would sing and play the lyre that hangs above him. The text on the scroll is difficult to read, but probably says “Muse, I begin to sing for myself of fine-flowing Scamander” mimicking an epic invocation.

From later periods, Greek musical notation survives, providing us with the melody for ancient songs. This recording, performed by Dr. James Lloyd, demonstrates the Seikilos Song, found on a grave marker in modern-day Turkey.This short song dates to the 1st or 2nd century CE, making it the earliest complete song with musical notation. It translates as: “While you live, shine / have no grief at all / life exists only for a short while / and Time demands his due.”

Credit line - Photo Antikensammlung Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Aulos

The aulos, an instrument made of two separate pipes and reeds—like playing two oboes at once—was popularly taught in Athens in the early 5th century BC. Our example is one half of an aulos, and is crafted with skill, including bronze, ivory, wood, and even silver, so it is unlikely it was used in a schoolroom. The aulos could be a divisive instrument.

Writing in the 4th century BC, Aristotle, who clearly didn’t much like the aulos, tells us “at Athens it became so fashionable that almost the majority of freemen went in for aulos-playing … But later on it came to be disapproved of as a result of actual experience, when men were more capable of judging what music conduced to virtue and what did not….” The aulos remained popular in different parts of Greece, however, at parties, to accompany sacrifice, and even for the choruses of Greek drama.

This recording gives us a taste of what an aulos might have sounded like (improvised by Dr. James Lloyd in 2016 on a replica of the Louvre Museum aulos).

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology. Reco

Girls dancing

While most girls did not receive a formal education, they were taught music, including dance, from a young age by members of their household. Dance accompanied processions at funerals—as shown on this tankard—and even at special religious festivals. Poets led young girls in choruses, perhaps shown on our Corinthian skyphos, singing and dancing to their compositions. Through these performances girls learned about local myths, religious expectations and social hierarchies.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum

Maenads dancing

Girls and women called maenads, literally meaning ‘mad women’, might dance together also in the worship of Dionysos, as shown on the outside of this krater, a mixing bowl for wine and water. These worshippers of Dionysos danced in a frenzy to reach the ecstatic state that reflected their enthusiasm for the god’s spirit. The term maenad blurs the boundaries between reality and myth. While some performed rites, including dance, as worshippers, extraordinary deeds of maenads became the stuff of myth.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

Beating the drum

Whether in choruses, processions or other worship, tympana, a type of hand drum, added rhythm to dance, as shown on the front of this Apulian red-figure bell krater from the Reading Museum collection, where the women at left holds a large drum. Our Boeotian terracotta figurine represents a robed woman beating her hand on a such a tympanon, also used by Maenads to accompany their Dionysiac rites.

Credit line - Copyright Reading Museum

Feasting with music

Music education was important because of its presence at many of the key moments in Greek life. A wedding procession with lyre accompaniment might be shown on a cup and a skyphos in the Ure Museum. Women and men would play music and dance together at weddings and other feasts, as shown on this neoclassical cast of an ancient gem.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

Symposion

At parties called symposia, guests might take part in a singing game. They would swap verses from famous songs, or show off their skill and refinement in playing the aulos or lyre. At the same time, hosts might try to impress by hiring women to perform music. This lekythos shows a symposion. The white skin of the lyre player at the foot of the couch (now somewhat rubbed off) marks her as female. Musicians as well as hetairai—paid female companions—would entertain the men while they ate and drank. In both cases, alas, the women were subservient to the men.

Credit line - Copyright Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

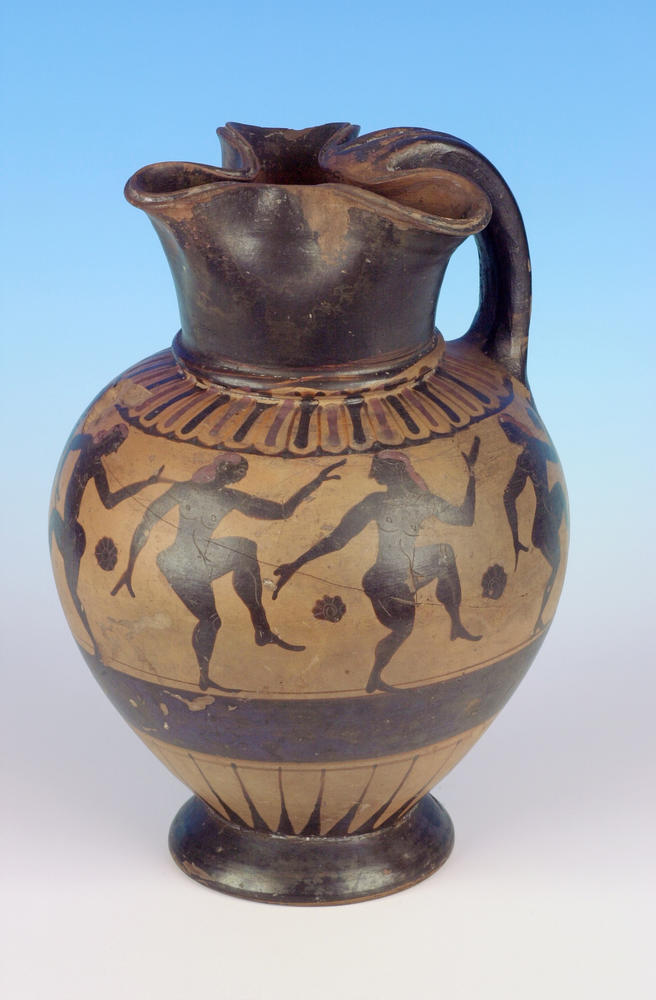

Komos

After a symposium there was often an after-party. The guests would take to the streets as a komos—a band of revellers—and dance through the night. This oinochoe (a wine jug) shows a type of komos, with eight nude men dancing. The krater shown under the handle alludes to the feast they are leaving. While the vase shape and image are essentially Greek, this is an Etruscan vase from Italy. The Greeks travelled and traded across the Mediterranean and brought their arts and customs with them.

Check out an animation of the figures on this oinochoe at Panoply.org.uk.

Credit line - Copyright Reading Museum