Troy: beauty and heroism

Following on from the major BP exhibition Troy:myth and religion, the Ure Museum is delighted to have hosted the first stop on A British Museum Spotlight Loan Troy: beauty and heroism.

Key objects from the BP exhibition were displayed alongside objects from the Ure Museum, Special Collections and the University of Reading’s library. The exhibition explored two central characters in the Trojan War: Helen- the most beautiful woman in the world and Achilles- the greatest warrior. The actions of Achilles and Helen were explored as well as the role of fate, responsibility, the nature of heroism, the power of beauty and the essence of love.

The wrath of Achilles

Achilles drags Hektor's body

Priam beseeches Achilles

Helen and the Trojans

Achilles and Heroism

The childhood of Achilles

Achilles' destiny

Journey to Troy

The fray of war

Warrior women

W.H.Auden

Heartless hero

Ambush of Troilos

Beautiful Helen

Destined Beauty

The goddess of love

The Judgment of Paris part 1

The judgment of Paris part 2

A married woman

Love and its blessings

A new love

Helen leaves for Troy

The face that launched

The many sides of Helen

Vision of beauty

Acknowledgments

The wrath of Achilles

The wrath of Achilles

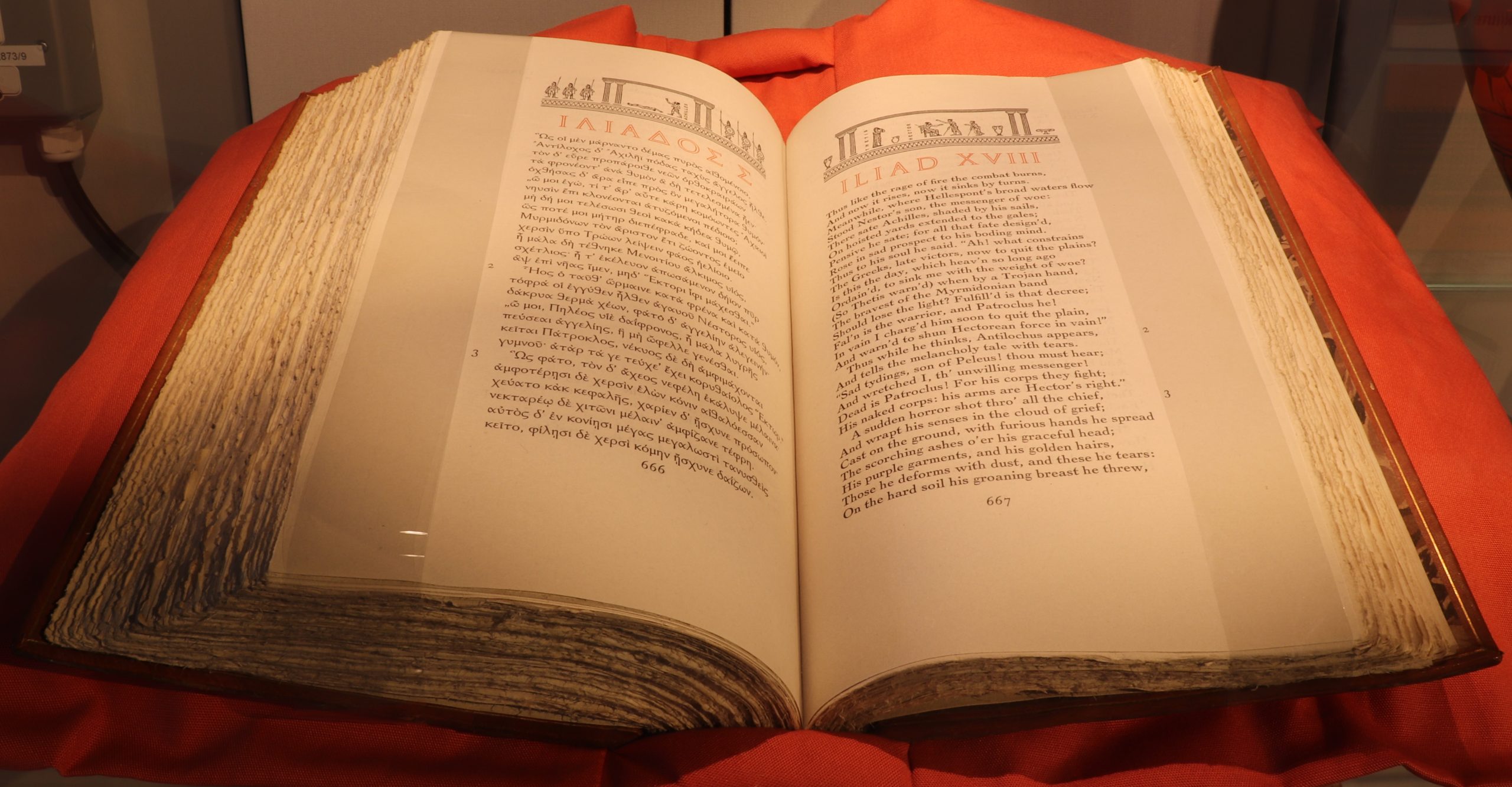

Homer’s Iliad (UoR Special Collections), original about 700 BC.

Iliad or The Song of Ilion (Troy), Homer’s epic poem, focuses on the quarrel between Achilles and King Agamemnon, the leader of the Achaian (Greek) coalition, in the last year of the ten-year Trojan War. It revolves around Achilles’ anger first at the loss of his captive woman, Briseis, and then at the death of his closest comrade and lover, Patroklos, at the hands of the Trojan Prince Hektor.

This 1931 edition by Alexander Pope has Greek text on the left and a translation in English on the right.

Achilles drags Hektor's body

Achilles drags Hektor’s body

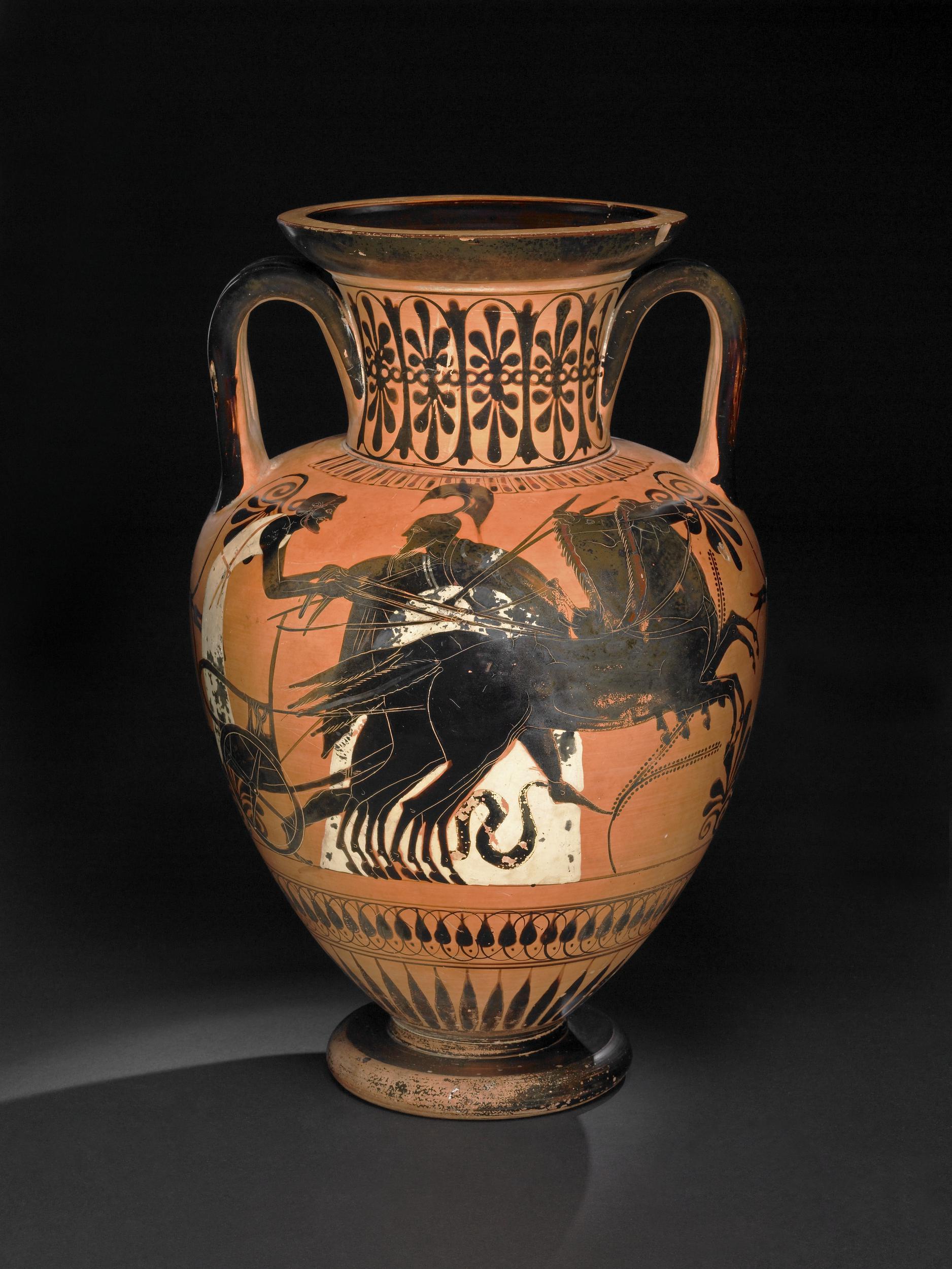

Athenian black-figure neck-amphora or jug (BM 1842,0314.2) from Vulci, Italy, 520–500 BC

The fight between Achilles and Hektor is a turning point in the Trojan War. In blind rage driven by grief for Patroklos, whom Hektor has killed, Achilles slays Hektor and drags his body behind his chariot. Here Achilles runs alongside the chariot, as a charioteer drives it around the tomb of Patroklos. Achilles’ sacrilegious behaviour outrages gods and men.

Priam beseeches Achilles

Priam beseeches Achilles

Gem impression cast in plaster of Paris (unknown manufacturer), showing Achilles with Priam (Ure 2008.2.1.74), 18th century AD

Achilles only regains his humanity when he returns Hektor’s body to his father, King Priam. By killing Hektor, Achilles not only removes Troy’s greatest protector, but fulfils a prophecy that seals his own fate: once Hektor dies, Achilles will soon be killed.

Helen and the Trojans

Helen and the Trojans

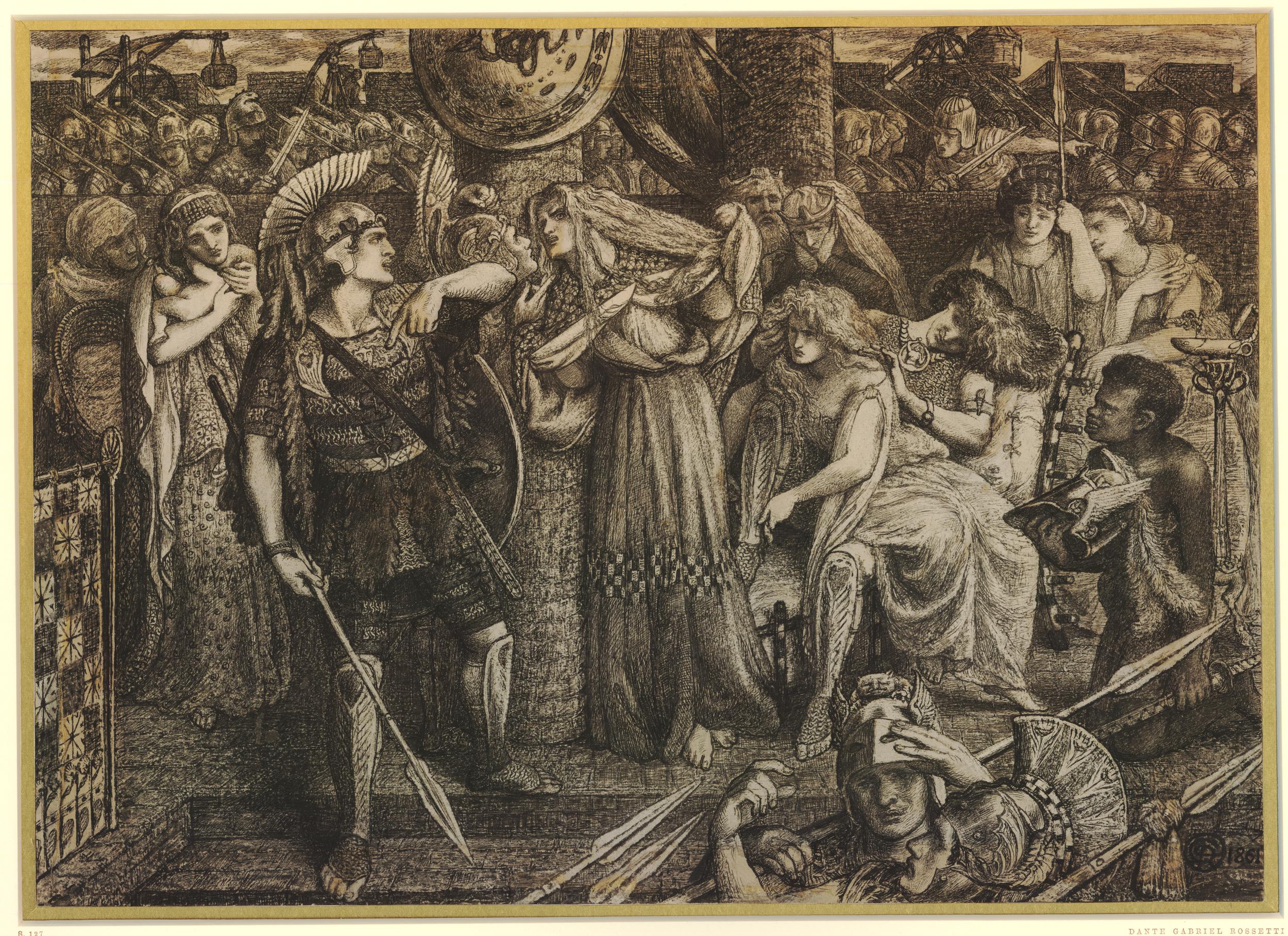

Cassandra, pen and black ink drawing by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (BM 1910,1210.4), AD 1861 (reworked 1867)

The Trojan princess Kassandra stands on the battlements of Troy as her brother Hektor leaves for battle. She foretells the destruction that Helen will bring but is fated never to be believed. All the men here – Hektor, his baby son, old King Priam, Prince Paris and the soldiers – will die. The women – Andromache (Hektor’s wife), Queen Hekabe and Kassandra – will endure rape and enslavement at the hands of the Achaians. Helen and Paris appear unconcerned. Helen pouts, sitting in the lap of Paris and languidly fitting her lover’s armour, while a black servant holds his spear and helmet. Like other Pre-Raphaelite artists, Rossetti (1828–82) was fascinated by strong women.

Achilles and Heroism

Achilles, son of the mortal King Peleus and immortal Thetis, was considered ‘best of the Achaians’: noble, beautiful, brave and even wise, educated by the centaur Chiron on Mount Pelion. Achilles is fated to die prematurely, so his mother tries to protect him and then hides him – disguised as a girl – on the island of Skyros. Clever Odysseus uncovers this ruse and takes Achilles to Troy to join his fellow Greeks at war. Achilles legendarily participated in many battles, including the battle of the Greeks against the warrior women known as Amazons. Achilles’ anger is the central theme in Homer’s tale of the Trojan War, the Iliad. When the enslaved woman Briseis is taken from him, Achilles refuses to fight, which leads to the death of Patroklos. In his heroic desire to avenge Patroklos’ death, Achilles finally returns to the battlefield. Heroic justice disappears when vengeful Achilles drags the dead body of Hektor, crown prince of Troy, for 12 days. The epic poem Kypria tells us of another act of questionable heroism, that Achilles ambushed Hektor’s younger brother, Troilos, at a water fountain.

The childhood of Achilles

The childhood of Achilles The birth and infancy of Achilles, etching by Pietro Testa (BM V,10.141), ca. AD 1648–50

In this etching Baroque artist Testa (1612–50) shows Thetis’ attempt to protect her son Achilles from his destiny with water from the Styx. In the background, the boy Achilles is handed over to the centaur, Chiron, to learn the arts of war and medicine. His upbringing makes him the perfect hero. Ultimately, he chooses an early death at Troy and eternal fame over a long, but ordinary, life. This etching is part of the Life of Achilles series Testa made at a time of renewed interest in the hero’s story.

Achilles' destiny

Achilles’ destiny Bronze arrowhead (Ure 26.7.13) said to be found on the summit of Mount Helikon, Boeotia, ca. 8th–6th century BC

Achilles choose to gain glory and die young, according to Homer’s tale, rather than to have a long and uneventful life. Yet time and again his mother, the sea nymph Thetis, tries to change his fate. First she dips baby Achilles into the water of the river Styx to make his skin impenetrable. Yet the part she holds onto – variously translated as ankle or heel – remains untreated and becomes his one weakness. A tiny arrowhead, like this bronze one, would eventually kill him. This rhombic arrowhead would have been attached to a wooden shaft and used with a bow.

Journey to Troy

Achilles’ journey to Troy Gem impression cast in plaster of Paris (unknown manufacturer), showing a warrior (Ure 2007.9.3.54), 18th century AD

A naked man, carrying a sword and bow, disembarks from a ship. The image epitomises the ancient Greeks’ perception of beauty and power exhibited through exercise and martial prowess. As ‘best of the Achaians’ Achilles chooses to journey to Troy with his fellow Myrmidons to fight against the Trojans, even though he is fated to die.

The fray of war

The fray of war Euboean black-figure lekanis showing warriors among onlookers (Ure 56.8.8), ca. 550 BC.

The creator of this lekanis, or shallow bowl, decorated its exterior with images of runners, warriors engaged in battle and veiled onlookers. The veils may indicate age or gender or suggest the sacred aspect of warfare. The Panoply vase animation project has produced an animation of this lekanis, available here.

Warrior women

Warrior women Athenian black-figure lekythos, attributed to the Painter of Vatican G12, showing Greeks (including Achilles?) fighting Amazons (Ure 51.4.9), ca. 525– 500 BC.

Battles of Greeks against Amazons, the warrior women of the Eurasian plains east of Greece, featured in many epics, most now lost, as well as the arts of Greece and later Rome and Etruria. Achilles was just one of many warriors to come into conflict with these armed women. The central hero depicted on this lekythos could be interpreted as Achilles because he doesn’t have the hallmark lion-skin of Herakles, yet might also represent the Athenian king and hero, Theseus. As in the stories of each of those heroes, Achilles falls in love with an Amazon queen, Pentheseleia, but tragically at the moment that his sword penetrated her neck.

Glittering armour

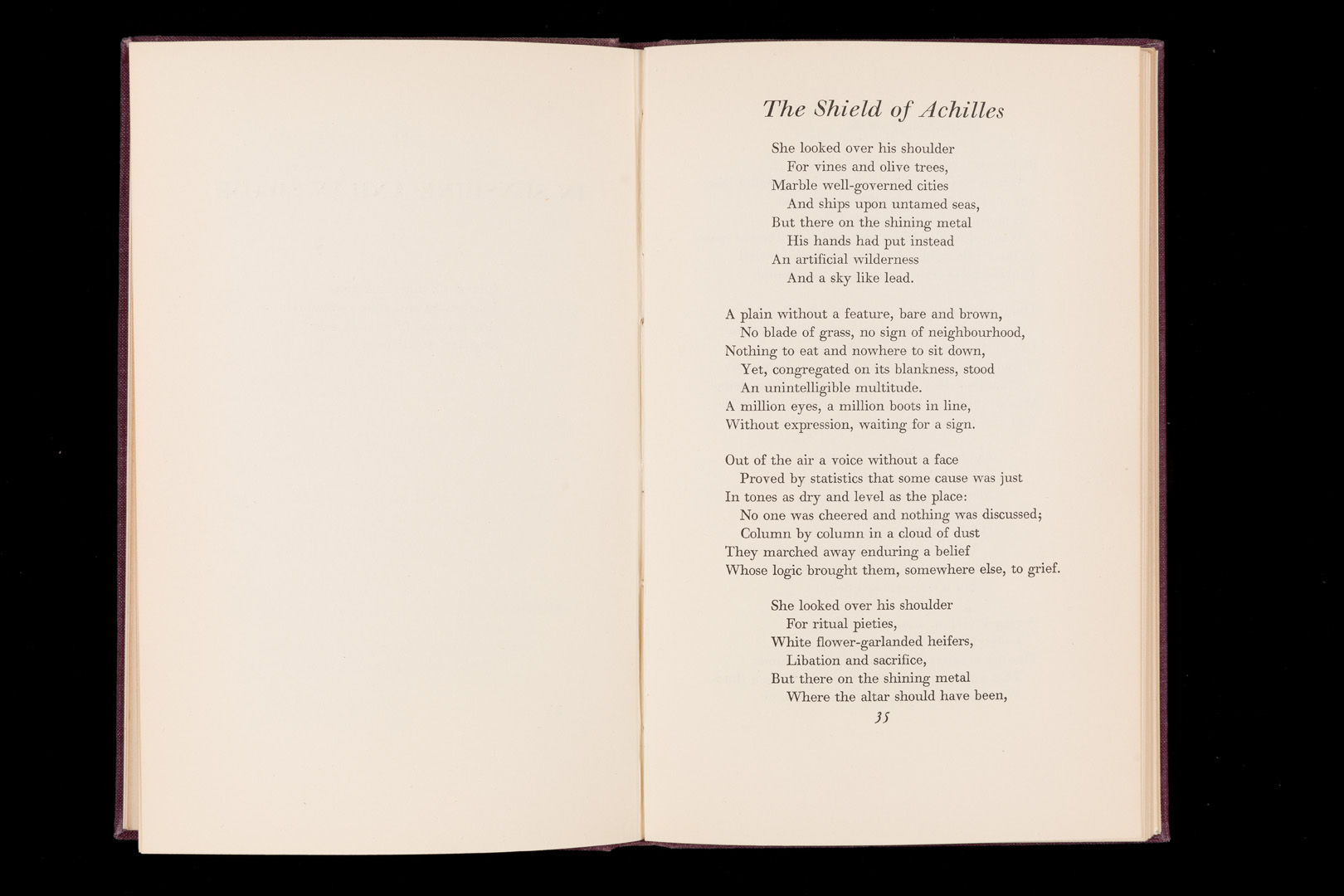

W.H. Auden, The Shield of Achilles (UoR Library), AD 1952

Before Achilles returns from his sulk to fight against the Trojans he needs new armour. His own armour, which he had lent to Patroklos, has been taken by Hektor as war booty. His mother Thetis persuades the smithgod Hephaistos to forge replacement armour, including an elaborate shield. Homer’s ekphrasis or detailed description of the shield details 9 bands of images ranging from the kosmos (universe) to a sheep farm! It inspired many other poets and artists such as Auden to interpret and reimagine Achilles’ shield in their own times.

Heartless hero

Heartless hero Gem impression cast in plaster of Paris (manufacturer unknown) showing Achilles dragging Hektor’s body (Ure 2007.10.2.155), 18th century AD.

Epics and other arts, from antiquity to today, present a range of Achilles’ positive character traits, from his bravery and military prowess to his love for and loyalty to his closest friends. They also present a cruel man who seems like an anti-hero by contemporary standards. After Achilles kills Hektor, for example, instead of leaving the body so that the Trojan could receive a proper funeral, Achilles straps the body to his chariot and drags it around the city walls, for all – especially Hektor’s family – to see.

The ambush of Troilos

The ambush of Troilos Etruscan black-figure amphora, attributed to an artist akin to the Tityos Painter, showing Achilles ambushing Troilos (Ure 47.6.1), ca. 550 BC

Achilles’ anti-heroic tendencies are exhibited also in his ambush of Prince Troilos, the youngest of King Priam’s sons. It had been predicted that Troy would not fall until Troilos had been killed. So Achilles ambushes Troilos at a water fountain where the young prince is helping his sister Polyxena to fetch water. The prominent fountainhouse, triumphant rider and dark-skinned body (Troilos) on this Etruscan amphora indicate all the aspects of this tale except the princess Polyxena.

Beautiful Helen

Helen also had divine parentage, born from the union of Queen Leda of Sparta and the sky god Zeus, in the form of a swan. So famous was Helen for her beauty that Aphrodite, the goddess of love, awarded her as a prize, to Prince Paris of Troy. But Helen was already married, to King Menelaos of Sparta. When Paris took Helen away, her husband sought to recover his wife through force, triggering the epic battle between Greeks and Trojans. Helen’s role in these events remains unclear: was she really a heroine? In Homer’s Iliad, Helen appears shameful while, in his play Helen, Euripides blames the ‘fatal nature’ of her beauty. The poet Sappho – a rare female voice preserved among ancient Greek writers – explains that Aphrodite led her astray, towards desire. Helen’s beauty made her an object of male desire, a tool to be used by men and gods. Or did Helen use her beauty to gain power in a world run by men? Yet Helen represents women who endure, despite objectification. Ancient and modern concepts of beauty differ. The Greek word for ‘beautiful’ – kalos – translates also as ‘good’ and ‘noble’. It is used to describe things as diverse as marriage, craft, war and heroism: just as Helen is a beautiful heroine, so Achilles is a beautiful hero.

Destined beauty

Destined beauty Boeotian terracotta figurine of Leda and the swan (Ure 34.10.23), ca. 400–375 BC.

This moulded, once painted, terracotta figurine, shows Leda, Helen’s mother, wrapped in a himation (cloak) and holding a swan, the manifestation of Zeus when he forced himself upon her. This image, which is repeated in stone sculpture, mosaics, paintings and even jewellery from Greek and Roman antiquity, captured the imagination of Renaissance and later artists. The awkward circumstances of Helen’s conception and her birth from an egg call into question her destiny. Is Helen’s beauty simply a characteristic of divine parentage or was her beauty a deliberate act of Zeus, part of his plans to bring about the war on Troy? Is Helen a victim of her own beauty?

The goddess of love

The goddess of love Marble statue of Aphrodite with Eros, from Cyrene (Ure L.2005.10.3 on loan from the British Museum), ca. 1st century BC.

When Greeks established a colony at Kyrene in North Africa, in the 9th century BC, they brought with them Aphrodite, the goddess of seafaring, as well as love, beauty and much else, for whom they established a sanctuary. Even in Roman times, to which this statue may date, Aphrodite was worshipped at Cyrene, under the Latin name Venus. Eros/Cupid, her son whose name means ‘Love’ itself, is connected with her throughout images as well as poetic renditions.

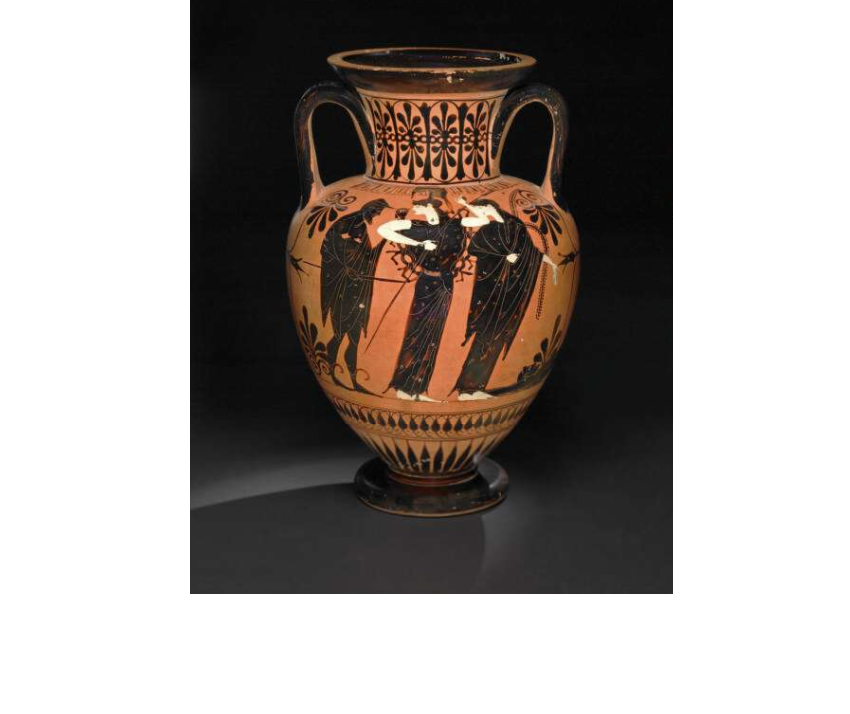

The judgment of Paris part 1

The judgment of Paris Athenian black-figure neck-amphora or jug (BM 1842,0314.2) from Vulci, Italy, 520–500 BC.

The gods play a central role in the Trojan War. Here the messenger god Hermes stands with war-like Athena and glamorous lovely Aphrodite, preparing for the Judgment of Paris. This is a beauty contest in which Athena and Aphrodite argue with Hera over which of them is the most beautiful goddess. They each offer a bribe to Trojan prince Paris, who is asked to judge. Aphrodite, goddess of love, wins, perhaps because she promises Paris the most beautiful woman in the world. Because that woman, Helen, is already married to a Greek, the Trojan war ensues. Here Aphrodite gestures towards the dead body of Hektor, on the other side of the jug, as though foreshadowing the terrible consequences of the beauty contest.

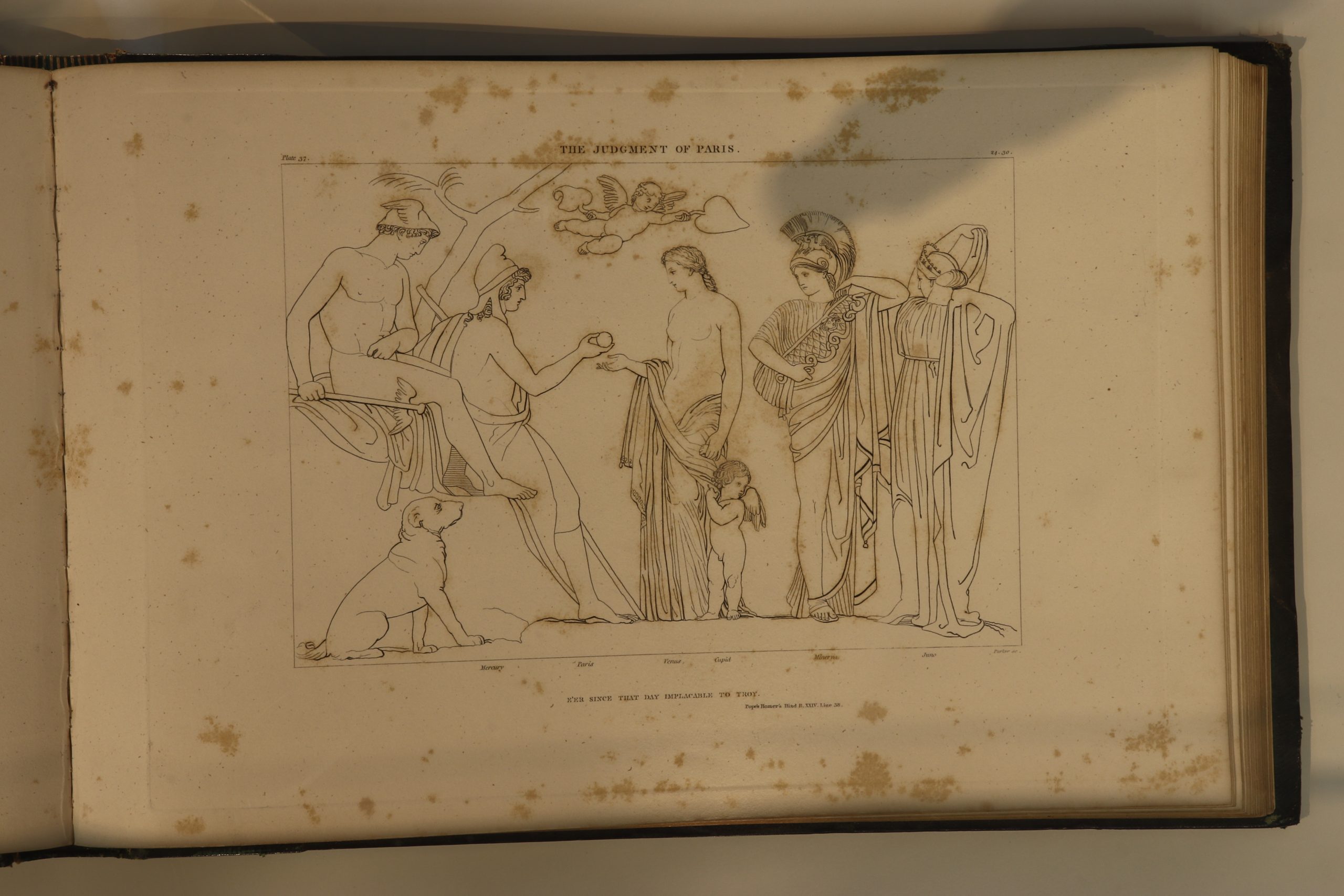

The judgment of Paris part 2

Depictions of the judgment of Paris can be found throughout history, here we see the sculptor and draughtsman John Flaxman’s engraving of the scene from his 1805 version of The Illiad of Homer (on loan from UoR Special Collections).

A married woman

A married woman Athenian black-figure skyphos, attributed to the White Heron Group, decorated with a wedding procession (Ure 26.12.10), ca. 525–500 BC.

Unsurprisingly for such a famously beautiful princess, Helen has already been married off before the Judgment of Paris, to King Menelaos of Sparta. Greek weddings, as shown on the outside of this skyphos, were big events that brought the whole community and even neighbours to witness the sacred union of two individuals, which cemented family connections. Menelaos was important in his own right but with the help of his brother, King Agamemnon of Mycenae, he was able to gather all the Greeks to avenge the insult at the loss of his bride.

Love and its blessings

Love and its blessings Athenian red-figure squat lekythos, attributed to the Makaria Painter, showing enthroned Aphrodite with her assistants (Ure 52.3.2), ca. 425–400 BC.

From persuading a couple to marry, to wedding preparations, to blessing a happily wedded couple, Aphrodite was assisted by many helpers who the Greeks thought accompanied her in her flourishing garden. On this oil jar, which might have served as a wedding present, she is surrounded by Eutychia (Prosperity), Eros’ brother Himeros (Desire) and Makaria (Blessedness). Small labels written in white identify each of the characters.

A new love

A new love Apulian red-figure alabastron, attributed to the Alabastra Group, showing a standing man courting a seated woman (Ure 49.1.2), ca. 350–325 BC.

Many ancient images like this one suggest the courtship of men and women, as on this alabastron or perfume vessel that might have been a wedding gift or even an engagement gift. It is unclear how, if at all, Paris courted Helen. We cannot know therefore whether she was persuaded by Paris, Aphrodite, Eros or other gods to elope with him, or whether she was taken against her will. Do you think she should share the blame for the resulting war?

Helen leaves for Troy

Helen leaves for Troy Relief from an Etruscan funerary urn (BM 1849,1201.6) from Italy, ca. 125–100 BC.

The Trojan prince Paris takes Helen across the sea to his home in Troy. Here Paris sits by his ship while Helen – just another treasure he is stealing from Greece – is pushed along reluctantly. Helen has become a powerless tool that the gods use to destroy Troy. The unknown artist of this funerary urn may have shown an unwilling Helen to symbolise the dead person reluctantly parting from life.

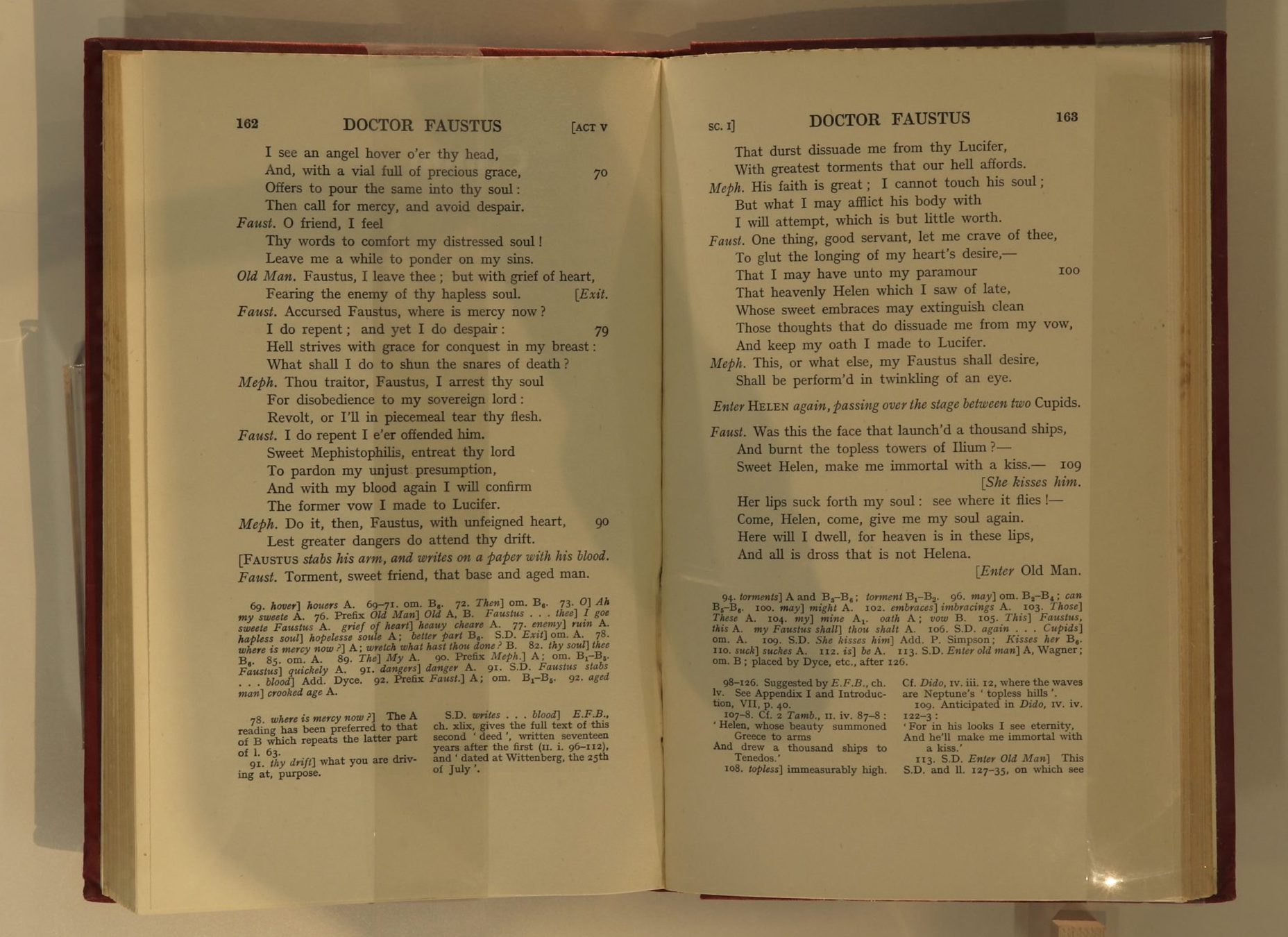

A face that launched a thousand ships

The face that launched a thousand ships Christopher Marlowe, The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (UoR Special Collections), 1604 AD.

In this Elizabethan tragedy, and Goethe’s later rendition (1772–1775), while selling his soul to the devil, the ambitious yet gullible Doctor Faustus conjures up the image of Helen of Troy. When he sees the famous heroine he questions “was this the face that launched a thousand ships / And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?” Do you think Faust doubted the claims of her beauty?

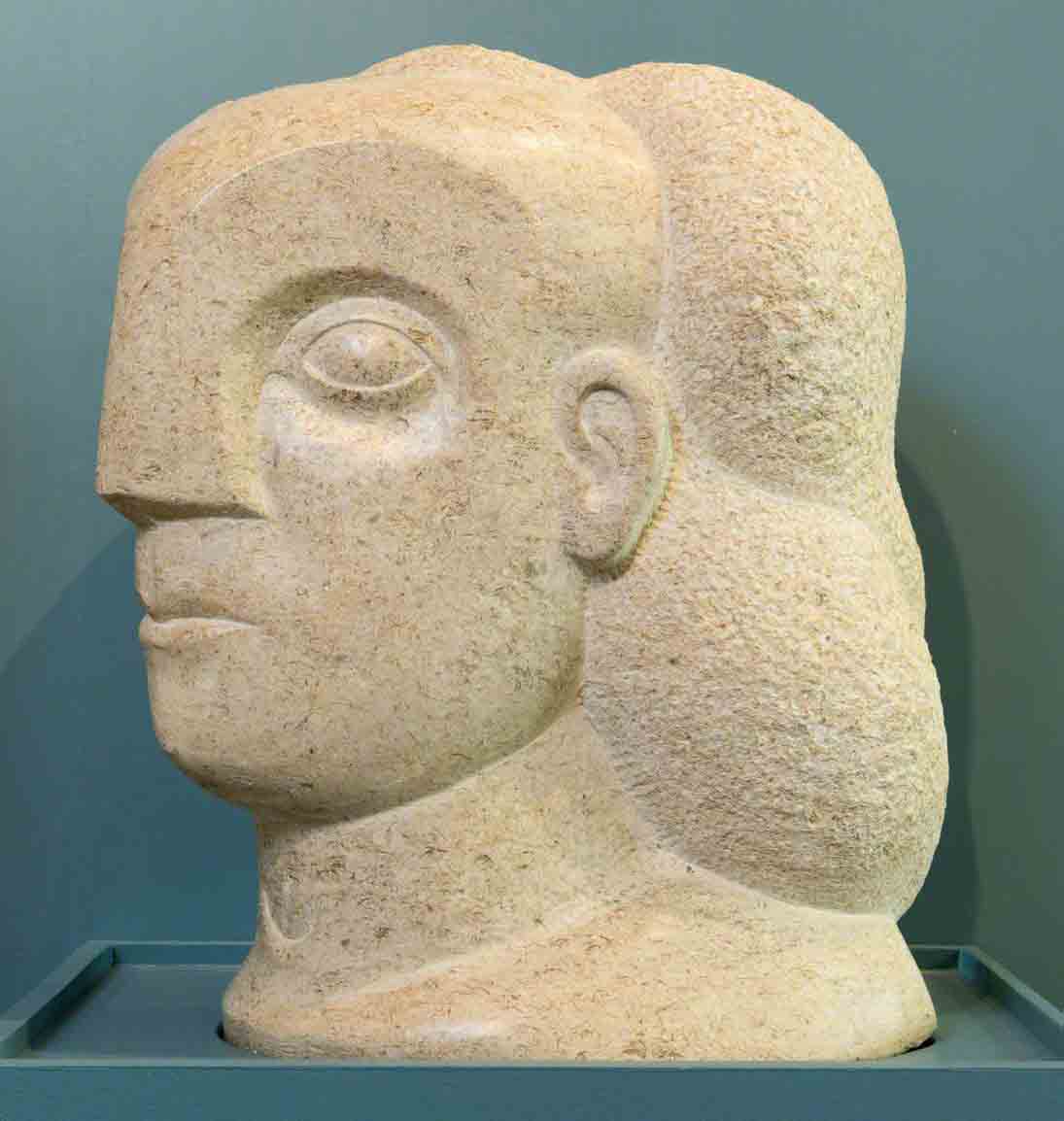

The many sides of Helen

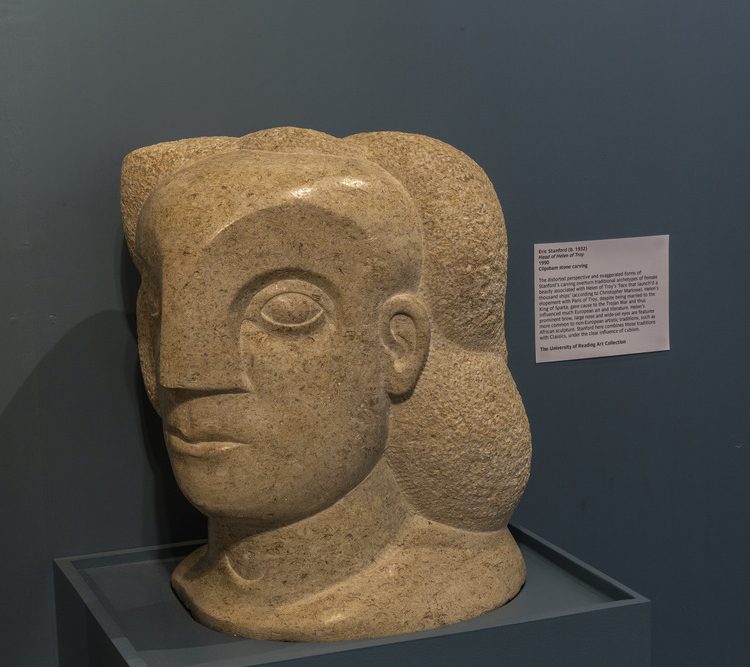

The many sides of Helen Head of Helen of Troy, a Clipsham stone carving by Eric Stanford R.A. (UoR Art Collection), AD 1990.

With distorted perspective and exaggerated forms, perhaps influenced by cubism, Eric Stanford (1932–2020) encourages a reconsideration of ideals of beauty. His Helen’s prominent brow, nose and eyes, which are widely set, characterise non-European artistic traditions which he has here adapted in one of his sculptures inspired by Classical myth.

Vision of beauty

Vision of beauty Copper Egyptian mirror with wooden handle (Ure E.65.12 and E.62.19 ), Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030– 1650 BC).

While Helen’s beauty was undisputed in ancient texts, ideals of beauty have changed throughout time and place. Her fame spread abroad and, in one dramatic telling, Euripides suggests that she never set foot in Troy but was in Egypt, where she could have reflected on her own fate in this mirror. Like a tarnished mirror, Helen’s character does not always reflect the beauty with which the Greeks credited her. From the remorseful victim of men and gods to the sly seductress, each representation of Helen brings into question her motives, so we must make up our own minds on Helen’s intentions.

Acknowledgments

This exhibition was curated by Jayne Holly and Amy C. Smith, with contributions from Sadie Pickup and Claudina Romero Mayorga. We are thankful to Chiara Manieri for the drawings of artefacts in the Ure Museum. It is part of a national tour, supported by the Dorset Foundation in memory of Harry M. Weinrebe, which follows on from the major British Museum BP exhibition Troy: Myth and Reality as part of the Museum’s National Programmes, allowing key objects from the exhibition to be accessible to audiences around the UK. The tour will also include visits to the Haslemere Educational Museum in Surrey from 10 February–8 May 2022 and The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery & Museum, between 19 May until 14 August 2022.