Monsters: From Ancient to Modern

The Department of Classics at the University of Reading co-hosted the Limina Journal Monsters Conference with the University of Western Australia in September 2022. This temporary exhibition was designed for the conference using objects from the Ure Museum collection, the University of Reading Library, and private collections.

In particular, this exhibition focuses on how ancient Greco-Roman monsters have been translated into contemporary culture. It looks at these monsters in four categories: female monsters, sea monsters, heroes and monsters, and hybrids and cyborgs. Take a look at an online version of Monsters: From Ancient to Modern below and discover how ancient monsters have crept their way into our modern society.

Click here to watch a video of the exhibition

Female Monsters

Gorgons

Medusa

Medusa

Witches

Sirens

Femmes Fatales

Mermaids

Scylla

Sea Monsters

From Triton to Aquaman

Heroes and Monsters

Herakles

Hybrids and Cyborgs

Chimera

Griffins

More Cyborgs

Medieval

and Modern

Acknowledgements

Female Monsters

The patriarchal images of Greco-Roman mythology remain firmly lodged within our cultural consciousness. The mythological figures of Medusa and the Sirens are two of the most enduring figures in depictions of the monstrous-feminine. It is not simply that the

monster is female, as this would imply a simple reversal of male monster. The monstrous-feminine horrifies because the construction of her gender is encoded into her

monstrosity. Driving this patriarchal hysteria is the fear that woman, as the object of the male gaze possesses the man with her own female gaze back. With Medusa and the Sirens, their beauty becomes the horror they inspire: she mystifies, seduces, castrates

(symbolically or literally), and destroys. These ancient archetypes provide the basis for countless modern manifestations of the monstrous-feminine. The ‘woman as castrator’ trope bled into the witch trials of the early modern period. Witches were accused of

rendering men impotent whilst also arousing uncontrollable sexual passion. From the femme fatale of film noir, through to the murderous mothers in Psycho, The Brood, Mommie Dearest, and Hereditary, in cinema the label of “monster” continues to punish

those who dare to transgress the boundaries of acceptable womanhood.

Gorgons

Three Gorgon sisters, Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa, were daughters of the sea gods, Phorcys and Ceto. Gorgons had snakes for hair, necks were protected by dragon scales, boar tusks, bronze hands, and golden wings. Their gaze could turn anyone to stone. Early myth had the Gorgons born as part of the pre-Olympian generation. The origin story of Medusa, the most famous Gorgon and the only one born mortal, however, evolved over the course of antiquity. Later myth had Medusa transformed into a Gorgon as a divine punishment: Medusa was a beautiful mortal girl who dared compare her beauty to that of the goddess Athena. Medusa was so proud of her hair that Athena turned it into a mass of snakes, and thus Medusa into a Gorgon. Another version has Athena punish Medusa because Poseidon raped her in Athena’s temple. Though a victim, Medusa was punished for the sacrilege.

A. Medusa with Boar Horns, Wavy Hair, and Knot at Throat Gem Cast, Date Unknown,

Ure Museum, 2009.9.178.

B. Gorgon with Snakes in Hair Gem Cast, Date Unknown, Ure Museum, 2007.9.3.75.

C. Medusa with Knot of Snakes Below Chin Gem Cast, Date Unknown, Ure Museum,

2009.9.184.

Medusa

This renowned Greek myth of Perseus and the monstrous Medusa is popular in the modern press—exemplified by Geraldine McCaughrean’s book—and cinema: Clash of the Titans (2010), a remake of a 1981 movie of the same name, follows the storyline of

Perseus in his battle against Medusa and Kraken (a sea monster). Perseus defeated Medusa with a polished shield reflecting her gaze that turned those she looked upon into stone. By viewing Medusa’s reflection in his polished shield, he was able to decapitate

the monster without himself turning to stone. Perseus had boastfully sought out Medusa and her head as a gift for his tyrant uncle, Polydektes. When Perseus at first could not

deliver upon his promise Polydektes forced Perseus to seek out and kill Medusa by threatening Perseus’ mother.

A. Perseus and the Gorgon Medusa, Written by Geraldine McCaughrean; Illustrated by Tony Ross London: Orchard, 1997. Loan from University of Reading Library. Image Source.

B. Clash of the Titans (2010), Directed by Louis Leterrier Screenplay by Travis Beacham, Phil Hay, and Matt Manfredi. Image Source.

Medusa

Luciano Garbati’s sculpture inverts the myth, whereby a beautiful rather than beastly Medusa carries the head of Perseus in one hand and her sword in the other. This statue is a reversal of Benvenuto Cellini’s 1545–54 bronze statue of Perseus with the Head of

Medusa in Florence, Italy. Garbati designed it as a presentation of “determined selfdefence” as opposed to Cellini’s work presenting “triumph”. The sculpture became a controversial symbol of female rage at the height of the #MeToo movement in 2018. The

sculpture still flips the script on a centuries old patriarchal story that blames the victim if they are sexually assaulted.

A. Perseus with the Head of Medusa, Benvenuto Cellini, c. 1545-1554, bronze cast. On Display in Loggia dei Lanzi, Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy. Image Source.

B. Medusa with the Head of Perseus, Luciano Garbati, 2008, bronze cast. On Display in Collect Pond Park, Lower Manhattan, New York, USA. Image Source.

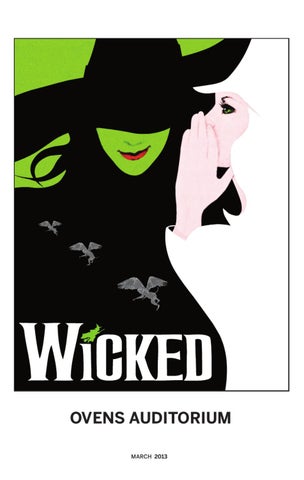

Witches

The 2003 mega-musical Wicked—based on Gregory Maguire’s novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West—tells the story of the Wicked Witch of the West from the perspective of the iconic green skinned villain herself In the 1939 film adaptation of The Wizard of Oz, the Wicked Witch is an ugly hag, determined to obtain the ruby slippers and conquer all of Oz. In Wicked, the Wicked Witch, now known as Elphaba, is rejected by her society because of her looks, but she gains love, and in turn

fear, due to her great magical powers. Embracing the fear she incites in others, Elphaba becomes the monster that the public believe her to be. She fakes her death to remove herself from society and live freely in a new world. Much like Circe in the Odyssey and Medea in Jason and the Argonauts, Elphaba is a woman of great power who is misunderstood and heralded as a monster by her peers.

‘Wicked’ Playbill, Musical by Winnie Holzman, 2003, Apollo Victora Theatre,

London, UK. On Loan from Private Collection. Image Source.

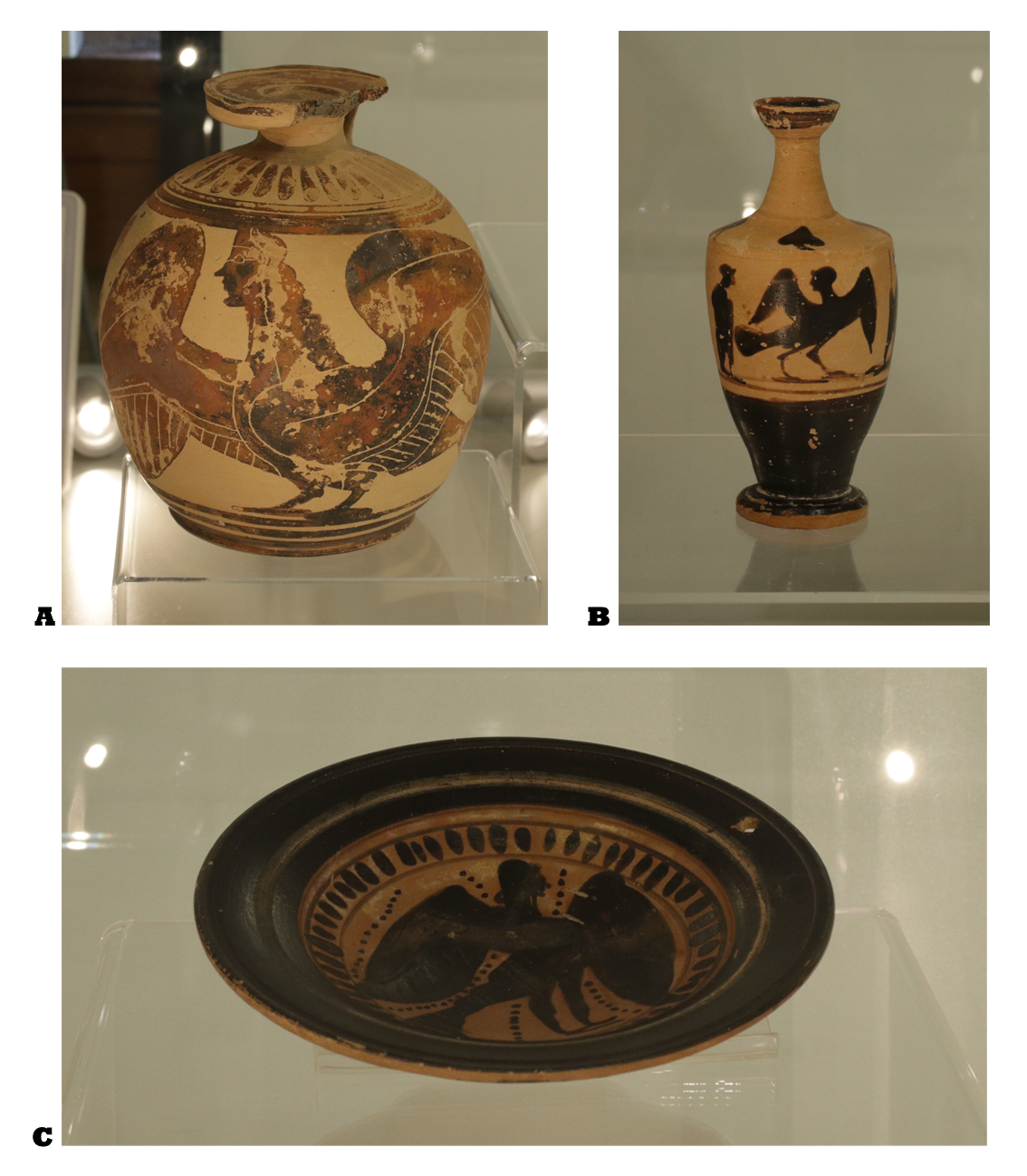

Sirens

The sirens of antiquity are femme fatales—or femme animales—women who catch and hold the gaze of men, but whose attraction is linked to the fact that they quickly turn away and shows little interest in their admirers. Which one of our ancient sirens on these

Greeks pots is looking away? Such is the case with the sirens in Homer’s epic, Odyssey, who only fall in love with Odysseus when he escapes their clutches. Known for their beauty and their enticing singing, these monstrous figures would lure in sailors causing

them to drown or wreck their ships on the Siren coast. Sirens encapsulated the reality of seafarer life; long months spent without family and the very real possibility of death or stranding due to shipwrecks. The legacy of the sirens live on, as we still use the term

siren to describe the sound of alarms that signal danger, emergency, or death.

A. Siren, black-figure plate, ca. 525-500 BC, Boeotian, Ure Museum, 51.1.4.

B. Siren between draped figures with staffs, black-figure Lekythos, ca. 550-525 BC, Attic, Ure Museum, 38.4.8.

C. Siren, Flat Bottom Aryballos, attrib. to the Torino Painter, ca. 575-550, Ure Museum, 37.7.1.

Femmes Fatales

O Brother, Where Art Thou? is a 2000 modern reimagining of The Odyssey, directed by the Coen Brothers. Our intrepid travellers are lured to a river when they hear the beautiful singing of three beautiful women, bathing in white transparent dresses. The sirens seduce the men before drugging them and turning one man into a toad. O Brother, Where Art Thou? signals the evolution of the half-woman half-bird sirens of antiquity to full the blown femme fatale or “screen siren”, a charming woman who beguiles unsuspecting

men.

A. O Brother Where Art Thou? (2000), Directed by Joel Coen, Written by Joel Coen and Ethan Coen. Image Source.

B. Sirens from O Brother, Where Art Thou? Image Source.

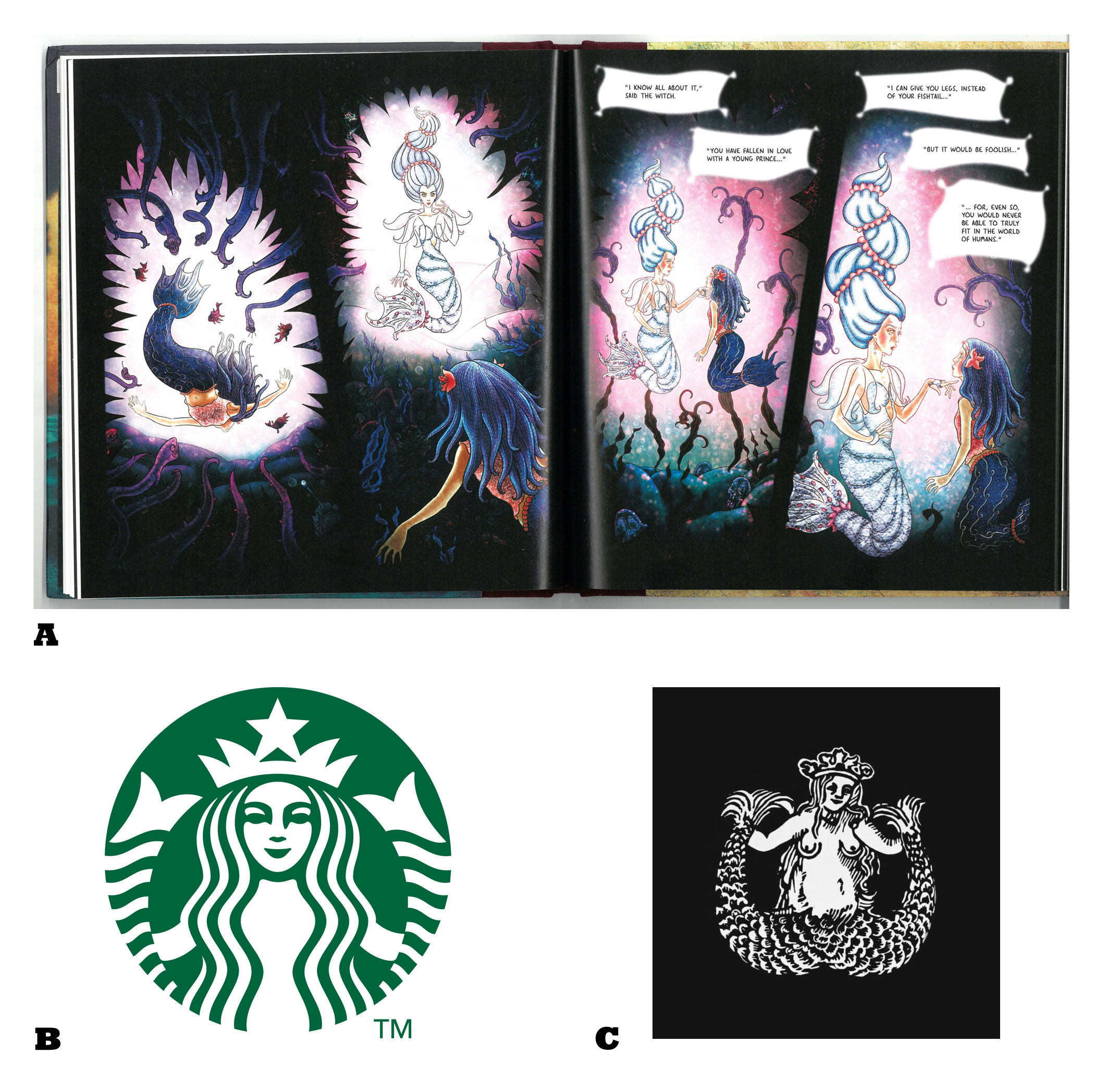

Mermaid

The sirens of antiquity are femme fatales—or femme animales—women who catch and hold the gaze of men, but whose attraction is linked to the fact that they quickly turn away and shows little interest in their admirers. Which one of our ancient sirens on these

Greeks pots is looking away? Such is the case with the sirens in Homer’s epic, Odyssey, who only fall in love with Odysseus when he escapes their clutches. Known for their beauty and their enticing singing, these monstrous figures would lure in sailors causing

them to drown or wreck their ships on the Siren coast. Sirens encapsulated the reality of seafarer life; long months spent without family and the very real possibility of death or stranding due to shipwrecks. The legacy of the sirens live on, as we still use the term

siren to describe the sound of alarms that signal danger, emergency, or death.

A. The Little Mermaid, Adapted by Metaphrog, Based on the Tale by Hans Christian

Andersen, Papercutz, 2017. Pages 40-41. On Loan from University of Reading Library.

B. Starbucks’ Logo Siren, Starbuck’s Coffee Cup 2022. Image source.

C. Terry Heckler’s original design for Starbuck’s logo based on 17th century woodcut. Image source.

Scylla

In Odyssey Odysseus and his men also encounter Scylla, a sea monster who lives in the Straits of Messina. She took the form of a woman with six dog heads around the lower portion of her body who devoured anyone who passed within their reach. She therefore

personifies seafarers’ fear of the unknown and the danger of open waters. On this gem cast Scylla brandishes an oar-like weapon in her right hand to fight a figure trapped in her tentacles. Like many other companies the data management company ScyllaDB adopted

this Greek mythic creature as their mascot, with their slogan “ScyllaDB is the Monstrously Fast + Scalable NoSQL Database.” They play on the fact that the Scylla is a scaly sea monster to advertise their business. Despite Scylla’s ‘monstrous’ nature, however, the company chose a cute cartoon characterisation of her.

A. Sea Monster (Probably Scylla), Gem Cast, Date Unknown, Ure Museum, 2007.10.2.357.

B. ScyllaDB Logo, Data Management Company. Image source.

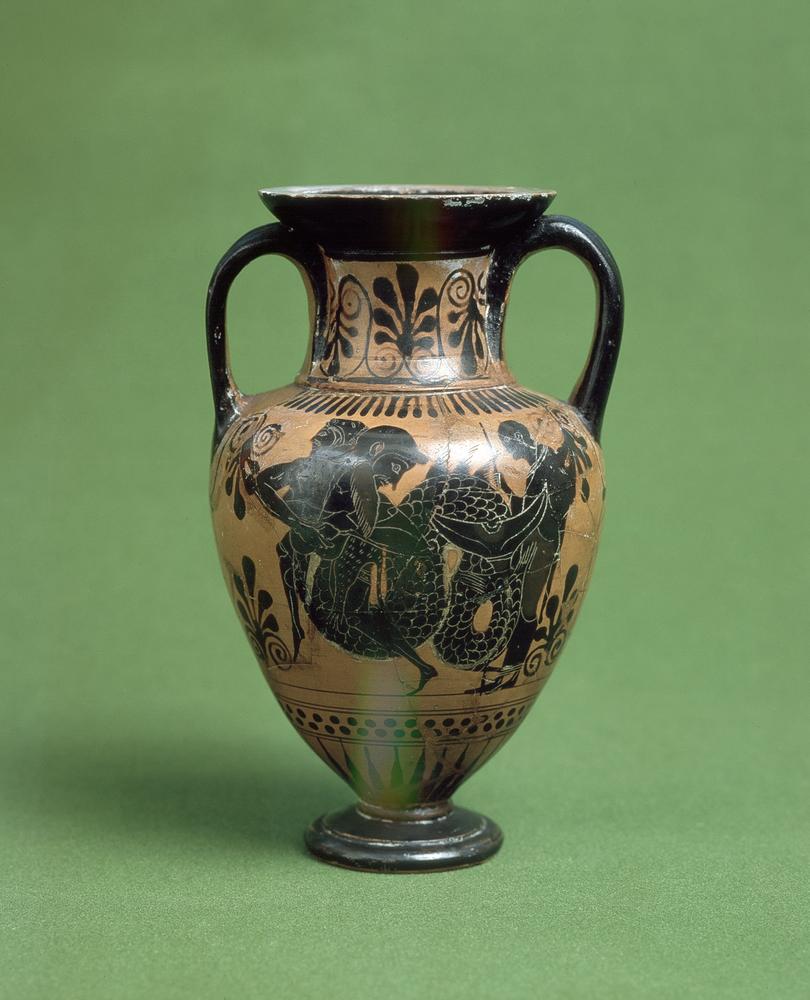

Sea Monsters

The deep sea is a foreboding environment—largely unexplored, unknowable, and overwhelming. Because the deepest parts of the sea have proven much more difficult to explore than land, they remain a reservoir of terrifying possibilities. It therefore comes as

no surprise that mythical sea monsters have been with us since antiquity. Greek heroes faced female monsters at sea, like sirens and Scylla, but also male monsters, including Triton, the god of the sea. Our fascination with sea monsters can be seen in the countless

hoaxes that have claimed to prove the existence of these fantastical creatures, and their consistent presence across popular culture and media, including Harry Potter, Pirates of the Caribbean, and The Little Mermaid. It is clear that the deep sea remains a place of

unending fascination and unending dread.

Herikles wrestling a sea monster (Triton or Nereus), black-figure, neck amphora, ca.525-500 BC, Attic, Ure 52.3.1

From Triton to Aquaman

Our Attic Amphora depicts Herakles fighting a snaky sea god, either Triton or Nereus.

Neither god was inherently evil, but they could fight mortals heroes, as shown here. Perhaps these gods represent seafarer’s prayers for a safe journey, or their fears of a watery grave. Aquaman, King of the underwater city of Atlantis and member of the Justice League, remained a less than noteworthy character for much of his existence. Jason Mamoa’s protrayal of him as seen in the FunkoPop! figure here has been the most popular potrayal yet. The launch of The New 52 (2011–16), which started a new zone in

the DC universe with new timelines and origin stories for the original Justice League members, began Aquaman’s trajectory towards popularity. He revealed his true potenial as a hero in this scene from Justice League (2011) #1 where parademons are attacking and Aquaman summons great white sharks to devour the monsters whole. Like Triton the hero controls the scariest sea creatures of the deep for his own ends.

A. Herakles and Triton or Nereus (Sea Monster), Black-figure Neck Ampohra, ca. 525-

500 BC, Attic, Ure Museum, 52.3.1.

B. Aquaman (2018) – Arthur Curry as Gladiator Pop! Vinyl Figure Funko. On Loan from Private Collection. Image source.

C. Justice League: The New 52 (2011), Issue #1 – Origin, Page 91. Image source.

Heroes and Monsters

A staple cornerstone in every civilisation’s mythology are tales of hero versus monster: Herakles versus the Hydra, Odysseus versus Polyphemus, Gilgamesh versus Humbaba, Beowulf versus Grendel. It is a tale as old as time: good versus monstrous evil. Many of

these myths portray a civilising process whereby the hero performs a service for the community by defeating the monster that is terrorising them. This justifies the hero killing the beast. Our modern superheroes continue to fight iterations of monsters in order to ‘save the day!’: Spiderman versus Dr Octopus, Superman versus Doomsday, Geralt and his Witcher brethren versus all the monsters on the Continent. We even take on the persona of hero/heroine in role-playing games (RPG) like Dungeons and Dragons, the Witcher series, and Bloodborne. But remember the wise words from Disney’s Hercules: “A true hero isn’t measured by the size of his strength, but by the strength of his heart.”

Herakles

Herakles, arguably the most famous ancient Greek hero, played a crucial role in battle between the Olympian Gods and the children of the Primordial Earth Goddess, Gaea, known as the Giants. He is better known for completing his Twelve Labours for his cousin, King Eurytheus, when he battled numerous monsters—including the Erymanthian Boar and Cerberus, Guardian of the Underworld, and Herakles against a Giant— shown on some ancient gems, here cast in plaster. Ancient Greeks and Romans wore these gems: perhaps the images of Herakles defeating monsters would help them face against evil in their daily lives. Disney’s Hercules (1994) (the Roman spelling of his name) casts Herakles in a loving-family with his parents Zeus and Hera. The film’s animation style has clear inspiration from Greek vase painting with spiral lines that define the bodies (notably at the chest, knees, and elbows). Monsters tests Herakles’ strength and establish his popularity amongst the mortals as a “hero”. It is only through his self-sacrifice to save his wife Meg, however, that he earns the true status of Hero.

A. Disney’s Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Hercules, By Bob Thomas Hyperion, 2nd ed., 1997.Pages 214-215. On Loan from the University of Reading Library.

B. Herakles and Cerberus Gem Cast, Date Unknown, Ure Museum, 2007.10.1.22.

C. Herakles and a Giant Gem Cast, Date Unknown, Ure Museum, 2009.10.2.319.

D. Herakles and the Erymanthian Boar Gem Cast, date unknown, Ure Museum, 2007.10.1.10.

Hybrids and Cyborgs

Famous hybrid monsters like the chimera and griffin are creatures composed of parts from multiple animals, like the snake, lion, eagle and of course human. Today, the word “chimera” is used to denote anything that is composed of different parts, whether animal or human. In the biological sciences, the term describes a combination of cells from different individuals. This form of gene editing has the capacity to revolutionise the critical shortage of organs for transplant. Nowadays we combine human parts with machines to make cyborgs. More and more artificial body parts are being implanted in us, effectively making us human hybrids or cybernetic organisms. Biological and genetic hybrids appear commonly throughout pop culture as is seen in games, movies and books like Dungeons and Dragons, Terminator, Hercules, and the Percy Jackson series.

Chimera

The three-headed monster known as the chimera lived in Lycia in Asia Minor. The child of Typhoeus and Echidna, she has the head and body of a lion, head of a goat attached to its back, and sometimes a tail that ends with the head of a snake. A fearsome being that breathed fire and ravaged the Lycian countryside, the chimera is now today defined as something that exists only in the imagination but not possible in reality. It has found its place in popular culture where various Chimera-like hybrids of animals, humanoids and humans can be seen in anime, TV series, films, books and even video games.

Chimera Gem Cast, date unknown, Ure Museum, 2009.10.2.360.

Griffins

As the ancient Greeks made contact with the cultures of Central Asia, folktales about the far Eastern griffin began to appear in Greek writings. The griffin is a mythical creature that has the body of a lion combined with the head and wings of an eagle. Griffins were said to be greedy, hoarding gold or laying eggs in nests covered in gold nuggets. The Greeks and Romans illustrated griffins as hybrids of two regal animals, with the strongest traits of both eagle and lion. On the outside of Corinthian convex pyxis the griffin, standing between two panthers, guard the contents of the container. Unlike other mythical creatures such as the Minotaur or Sphinx, it does not play a role in any surviving Greek mythological texts, nor interact with known mythical heroes. Nevertheless, fascination with the griffin was reignited by medieval legends which viewed the creature as a divine being. Popular in European symbolism, the “gryphus” in Greek became a very popular symbol for shields, coat of arms, and helmets due to its association with ideas of strength, valour, bravery and loyalty. Its likeness still features in modern architecture, logos, and literature. The griffin is not only popular in Europe but also finds its roots in Native American, Chinese, Indian, and Japanese myth and symbolism.

A. Griffin Gem cast, date unknown, Ure Museum, 2009.10.213.

B. Griffin between Two Panthers Pyxis, Attrib. to the Geladakis Painter, ca. 600-575 BCE, Ure Museum, 39.9.6.

More Cyborgs

The cyborg is frequently seen as a creature of modernity, a hybrid of machine and organism. However, the cyborg can also be interpreted as an extension of the creatures that populated Greek myth. The image on gem cast A could be considered an early representation of a cyborg as we know it today – part human and part invented organism. The fact that this monster is holding a spear and shield could denote that this enhanced individual or creature was a warrior. Human hybrids are no stranger, which was filled with monsters that embodied various forms of chaos. The image on gem cast B is also a precursor to the modern cyborg, integrating the head of a woman with the body of a spider to enhance her abilities and reach beyond the limitations of the human body. Such a cyborg is often seen as a utopian feminist figure, presenting opportunities for a postgender world.

A. A monster with eagle’s head, chest of a man, and two serpents for legs, holding a spear and shield Gem Cast, date unknown, Ure Museum, 2009.9.32.

B. Unidentified monster with human head, spider body, and holding cobras Gem Cast, date unknown, Ure Museum, 2009.9.42.

Medieval...

Bestiaries were one of the most popular forms of illuminated manuscripts in the Middle Ages. These books depicted a wide range of common and mythical creatures, from griffins and unicorns to lions and bears. The animals drawn in these books show us how the people of the Middle Ages understood the creatures around them, and those which they may not have seen. Exotic animals for Europeans, like apes and ostriches, would be designed using details from animals around them, creating chimeric creatures that intrigue and fascinate readers.

Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World, Edited by Elizabeth Morrison, Contribution by Larisa Grollemond. Getty Trust Publications, 2019. Pages 16-17. On Loan from Private Collection. Image source.

...and Modern

The iconic German Expressionist film poster of Fritz Lang’s 1927 science fiction film Metropolis created the foundations for the modern cyborg. Set in a dystopia where industrialists rule the underground-dwelling workers, a female robot is designed by the ruling elites to mimic the likeness of the workers’ revolutionary leader Maria and quash their uprising. While she is ultimately destroyed, this version of the cyborg is far from a feminist utopian figure. The film has been noted for its protofascist themes whereby workers and industrialists can cooperate in overcoming the contradictions of capitalism for the “greater good” of the nation.

Metropolis (1927), Directed by Fritz Lang, Screenplay by Thea von Harbou. Image source.

Acknowledgements

This exhibition was curated by the Limina Journal Monsters Conference Planning Committee. We would like to thank the Ure Museum, the University of Reading Library, Summer Courts, Meryt Ramble-Wallace, and the Classics Department Research Development Lead for providing the objects used in this exhibition. Special thanks to Jayne Holly, Amy C. Smith, and Matthew Knight for their help editing, installing, and photographing the exhibition. We would also like to thank Caitlan Smith for her graphic design work. A video tour of the exhibit, led by Edward A. S. Ross, is available on the Ure Museum YouTube Channel.