Locus Ludi: Anyone can play!

This exhibition was inspired by the European Research Council-funded project Locus Ludi: The Cultural Fabric of Play and Games in Classical Antiquity led by Professor Véronique Dasen (locusludi.ch).

It runs from Tuesday 5th of September to Thursday 30th of November 2023.

We would like to thank Colchester and Ipswich Museums, Reading Museum, the British Museum, The University of Reading’s Special Collections and Roland Cobbett for the loan of objects, and Matthew Knight, Juilette Quatre, and Giles Cattermole for their artistic and technical support.

We would also like to thank the Friends of the University of Reading and the University of Reading Arts Committee for a generous grant enabling the creation of a unique film from Panoply.org.uk to accompany the exhibition.

The exhibition pamphlet can be found here.

Infancy

Terracotta figurines

Phormiskos

Pottery Pig

Bes amulet

Childhood

Athenian chous

Greek and Roman dolls

Miniature vessels

Adolescence

Bronze Mirror

Spindle Whorls

Astragaloi

Counters

Adulthood

Game board tile

Dice

counter

Julii Pollucis

Dice tower

Old age

Old Age

Lamp drawing

Roman Urn

Roman Stele

Infancy

Our word infant comes from the Latin infans which means “not speaking” or “speechless”. Infancy in antiquity – between birth and the ages of 2 or 3 – was a time of great danger; many babies died of common illnesses. As today, infants needed comfort and entertainment in the form of toys. Ceramic figurines or models – found in temples, sanctuaries and graves but also in non-religious places – could be used as offerings to the gods and simultaneously items to play with [1–2]. Small children played with rattles in the ancient world too. They came in many shapes, sizes and materials, meaning they could be enjoyed by rich and poor [2–4]. When shaken, a pebble inside a ceramic rattle, remarkably similar in shape to modern children’s rattles, produces a rattling sound that entertains and calms an infant [2]. It also provides a focus to help develop hand and eye coordination. Some toys, like this ceramic pig [3] could also be used as rattles, as they also include ceramic nodules or stones that would produce sound when shaken. This pig is decorated with glass insets similar to those used to make gaming counters or to decorate jewellery and furniture; this highlights the challenges archaeologists face when identifying such items. Amulets could be worn for protection but also strung together to shake like rattles and provide comfort as teething aids. An amulet showing the ancient Egyptian god Bes might protect women in pregnancy and childbirth and infants from evil spirits [4].

1 Miniature terracotta body parts (two heads, a foot and an arm). Date unknown [Ure Museum 2003.7.29–32]

2 Boeotian terracotta rattle consisting of an elongated ovoid body tapering into a cylindrical handle with a rounded tip. Date unknown [Ure Museum 34.10.15]

3 Ceramic pig with glass insets. 2nd century BC–3rd century AD [British Museum 1756,0101.1014]

4 Egyptian blue faience amulet showing Bes as a dwarf with a plumed headdress. 664-332 BC (Late Period) [Ure Museum E.23.44]

1

Miniature terracotta body parts (two heads, a foot and an arm). Date unknown [Ure Museum 2003.7.29–32]

2

Boeotian terracotta rattle consisting of an elongated ovoid body tapering into a cylindrical handle with a rounded tip. Date unknown [Ure Museum 34.10.15]

3

Ceramic pig with glass insets. 2nd century BC–3rd century AD [British Museum 1756,0101.1014]

Credit line - Photograph by Ruth Allen

4

Egyptian blue faience amulet showing Bes as a dwarf with a plumed headdress. 664-332 BC (Late Period) [Ure Museum E.23.44]

Childhood

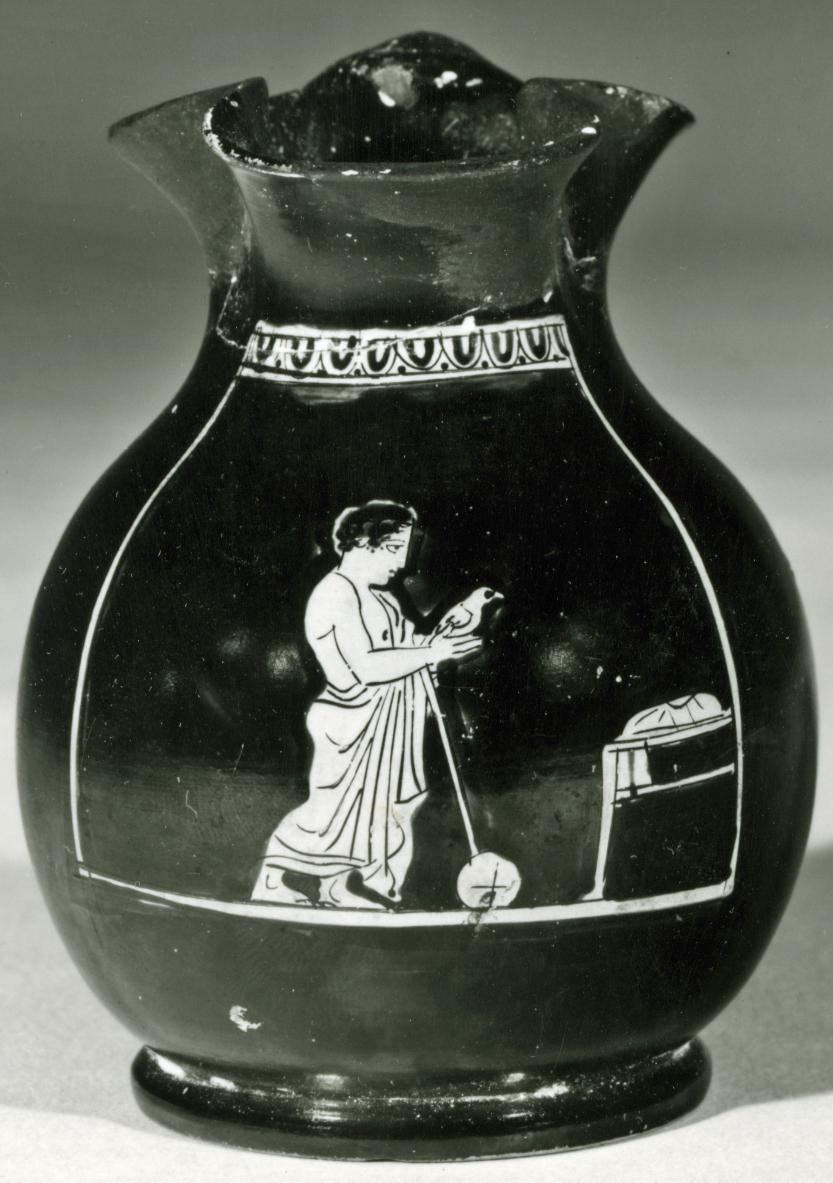

Childhood lasted until puberty, when the body began to prepare for adulthood, around age 14, or slightly younger for girls if they showed themselves to be ready for marriage. Boys from wealthy families would have formal education from the age of 7, while poorer boys would normally join their father at work from such a young age. For most girls a basic education centred around domestic tasks, managing a home. Children continued to play but with things that helped them develop, both physically and socially [5–6]. Athenians gave miniature choes or jugs to young people transitioning from infant to child, at a special day during the Anthesteria, a festival of Dionysos, the god of fertility and wine. Each chous, which held a child’s first drink of wine, was decorated with children engaged in play, for example a boy who uses his cart for role play [5]. Carts also helped with hand-eye coordination. His pet bird would have helped him learn responsibility. Terracotta figurines or dolls – found in tombs and religious spaces as well as non-domestic environments – encourage nurturing among girls. Our figurine, with an elaborate coiffure and musical instruments – cymbals or castanets – might also be interpreted as a ritual dancer [6]. Some argue that these dancing dolls are too fragile for play and served a purely ritual function. Girls mimicked the activities of adult woman – domestic and religious – with both dolls and miniature vessels [7]. Athenaios (AD 170–223) tells us that Greek girls would dedicate their toys, including dolls, to the virgin goddess Artemis before marriage, to mark the end of childhood.

5 Athenian red-figure chous or wine jug, with trefoil mouth, decorated with a boy, his bird and a cart. Circa 410 BC [British Museum 1928,0117.61]

6 Attic terracotta figurine of a dancer with cymbals. Circa 350 BC. Roman carved bone figure of a woman. Date unknown [Reading Museum REDMG:1997.15.1; British Museum 1865,0720.34]

7 Miniature pots from Laconia, including kraters and amphoras. 6th–4th centuries BC [Ure Museum 23.11.8–9, 11, 16, 22; 2007.2.21–25]

5

Athenian red-figure chous or wine jug, with trefoil mouth, decorated with a boy, his bird and a cart. Circa 410 BC [British Museum 1928,0117.61]

Credit line - © The Trustees of the British Museum

6

Attic terracotta figurine of a dancer with cymbals. Circa 350 BC. Roman carved bone figure of a woman. Date unknown [Reading Museum REDMG:1997.15.1; British Museum 1865,0720.34]

Credit line - © The Trustees of the British Museum

7

Miniature pots from Laconia, including kraters and amphoras. 6th–4th centuries BC [Ure Museum 23.11.8–9, 11, 16, 22; 2007.2.21–25]

Adolescence

Adolescence, after the onset of puberty, was when you were no longer considered a child. This stage lasted between the ages of 12/14 to 20. As in childhood, boys and girls were treated differently. Men would complete their education, start on their chosen careers, for example, training in specialised trades and start looking for suitable wives. Leisure time continued for pleasure and as a way to meet and discuss important matters and events. Women on the other hand married as soon as possible. During their short adolescence therefore, they might practise and perfect domestic skills, like cooking and childcare, but also beautification [8] and other preparations for weddings, including weaving [9]. Both men and women needed to practice numbers, for business and household economics, for which astragaloi (knucklebones) and other counting games helped [10–11].

8 Bronze mirror with engraved design of youth and girl playing a board game. 3rd–2nd centuries BC [British Museum 1898,0716.4]

9 Spindle whorls made of limestone and white paste, one from Diospolis Parva, Egypt, and another from Salamis, Cyprus. Dates unknown [Ure Museum E.62.32; 13.10.11.16]

10 Astragaloi (knucklebones) made from soapstone and bone, found at the Kabeirion, near Thebes, Greece. Date unknown [Ure Museum 25.6.4–6]

11 Bone inscribed counters with graffiti, found at Silchester. Various dates [Reading Museum REDMG:1995.1.127; REDMG:1995.1.131; REDMG:1997.3.6]

8

Bronze mirror with engraved design of youth and girl playing a board game. 3rd–2nd centuries BC [British Museum 1898,0716.4]

Credit line - © The Trustees of the British Museum

9

Spindle whorls made of limestone and white paste, one from Diospolis Parva, Egypt, and another from Salamis, Cyprus. Dates unknown [Ure Museum E.62.32; 13.10.11.16]

10

Astragaloi (knucklebones) made from soapstone and bone, found at the Kabeirion, near Thebes, Greece. Date unknown [Ure Museum 25.6.4–6]

11

Bone inscribed counters with graffiti, found at Silchester. Various dates [Reading Museum REDMG:1995.1.127; REDMG:1995.1.131; REDMG:1997.3.6]

Credit line - Copy rite Reading Museum

Adulthood

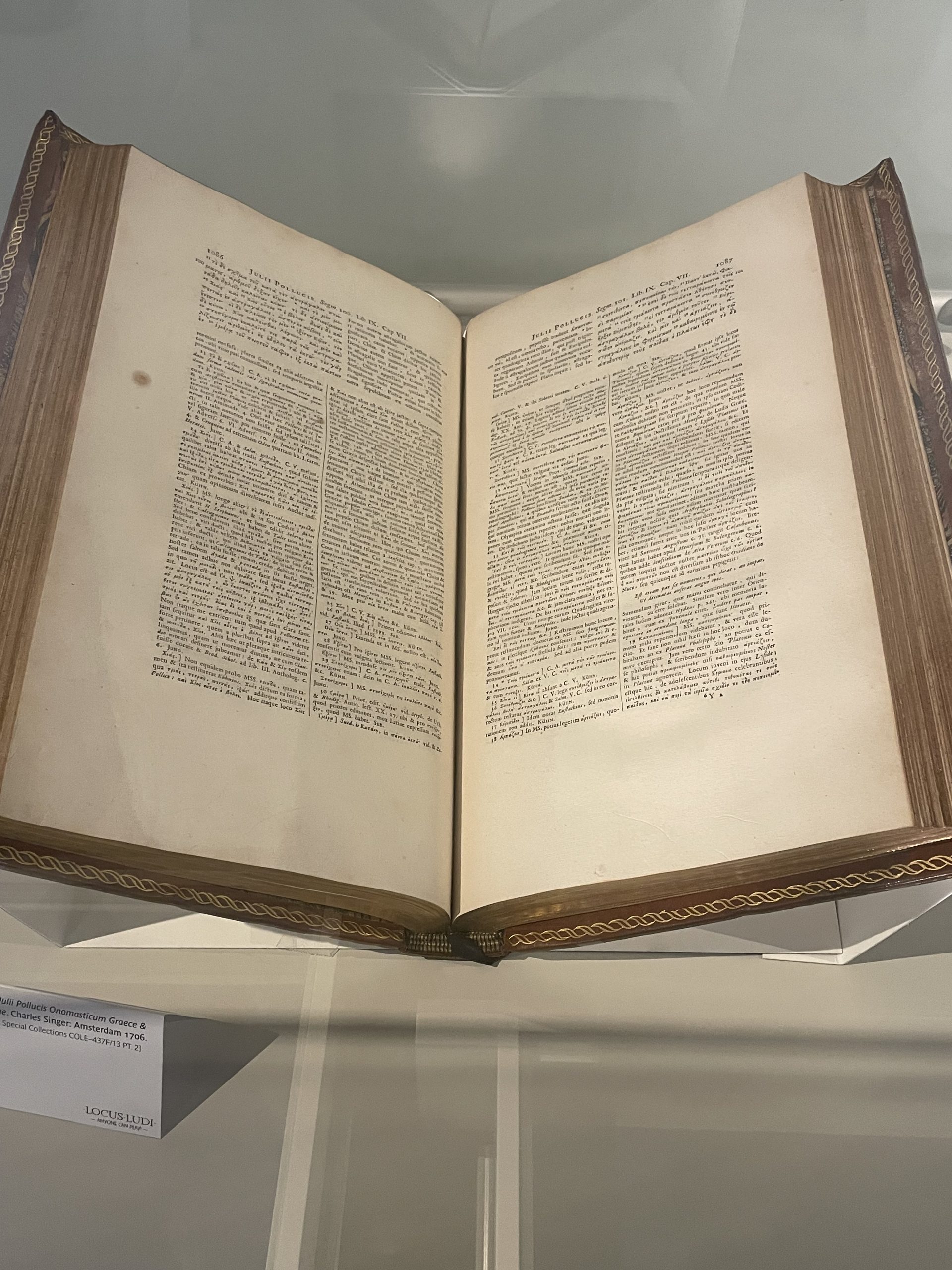

Next came adulthood, when a person was expected to have a profession, be married and start a family. A person’s profession and their duties within the wider community depended on their social status. Regardless of status, however, men had more leisure time then women, who were tied to household matters. Ancient sources tell us that adults spent leisure time playing board games with dice and counters [11–16]. In his Onomastikon, for example, Pollux informs us about games played on a board (9.97-98) and describes the playing of knucklebones (9.100) [15].

12 Image of a floor tile used as a games board, found at Silchester. Date unknown [Reading Museum REDMG:1995.1.186]

13 Ivory cubic die found in Egypt. 30 BC–AD 395 [Ure Museum E.62.16]

14 Egyptian faience counter found at Medum, Egypt. 945–712 BC [Ure Museum E.63.5]

15 Julii Pollucis Onomasticum Graece & Latine. Charles Singer: Amsterdam 1706 [UOR Special Collections COLE–437F/13 PT. 2]

16 Reproduction dice tower. AD 2018 [Private collection of Roland Cobbett]

12

Image of a floor tile used as a games board, found at Silchester. Date unknown [Reading Museum REDMG:1995.1.186]

Credit line - copyright of Reading Museum

15

Julii Pollucis Onomasticum Graece & Latine. Charles Singer: Amsterdam 1706 [UOR Special Collections COLE–437F/13 PT. 2]

16

Reproduction dice tower. AD 2018 [Private collection of Roland Cobbett]

Old Age

The fifth and final life stage, old age, began around the age of 60. At this point, people were expected to retire from active public life and focus on their families. During this life stage play became especially important as a way to pass the time. Older men and women were largely exempted from the social stigma associated with gambling and gaming. They also enjoyed playing with their children and grandchildren, thus using all of the games shown here.

When a person died, they might be buried with board games. The artefacts buried with a doctor in Stanway, Colchester during the 1st century AD. The included several ceramic dishes [17], amphorae, a copper alloy pan and strainer, six possible divining rods, a surgical set [18], a wooden game board [19] and 26 glass gaming counters [20]. Were these games offerings to the gods or useful items the decease might take to the afterlife? Might the skill and strategy involved in winning a game prepare a person for their journey to the afterlife? Or is simply that – like life itself – enjoyable things such as games must eventually come to an end.

Old Age

17 Ceramics from the Doctor’s Grave, Stanway: Samian bowl with potter’s stamp, carinated cup, terra rubra plate with potter’s stamp; terra nigra bowl and carinated cup, both with potters’ stamps; and cornice-rimmed flagon with four-ribbed handle. 1st century AD [Colchester Museum COLEM:1996.34.900.1, COLEM:1996.34.920.1; COLEM:1996.34.923.1; COLEM:1996.34.925.1 and COLEM:1996.34.927.1; COLEM:1996.34.C1077.1]

18 Reproduction artefacts from the Doctor’s Grave, Stanway: metal strainer bowl, tweezers, surgical instruments and divining rods. AD 2006, after originals circa 100 BC [Colchester Museum COLEM:SC.2023.1; COLEM:2001.232.7; COLEM:2001.232.1, COLEM:2001.232.6 and COLEM:2001.232.11; COLEM:2006.29.5–12]

19 Half-scale reproduction of maple game board, with brass hinges and corners, from the Doctor’s Grave, Stanway [Reproduction made by Giles Cattermole]

20 Twenty-six glass gaming counters found on a gaming board in the Doctor’s Grave, Stanway. 1st century AD [Colchester Museum COLEM:1996.34.97–122]

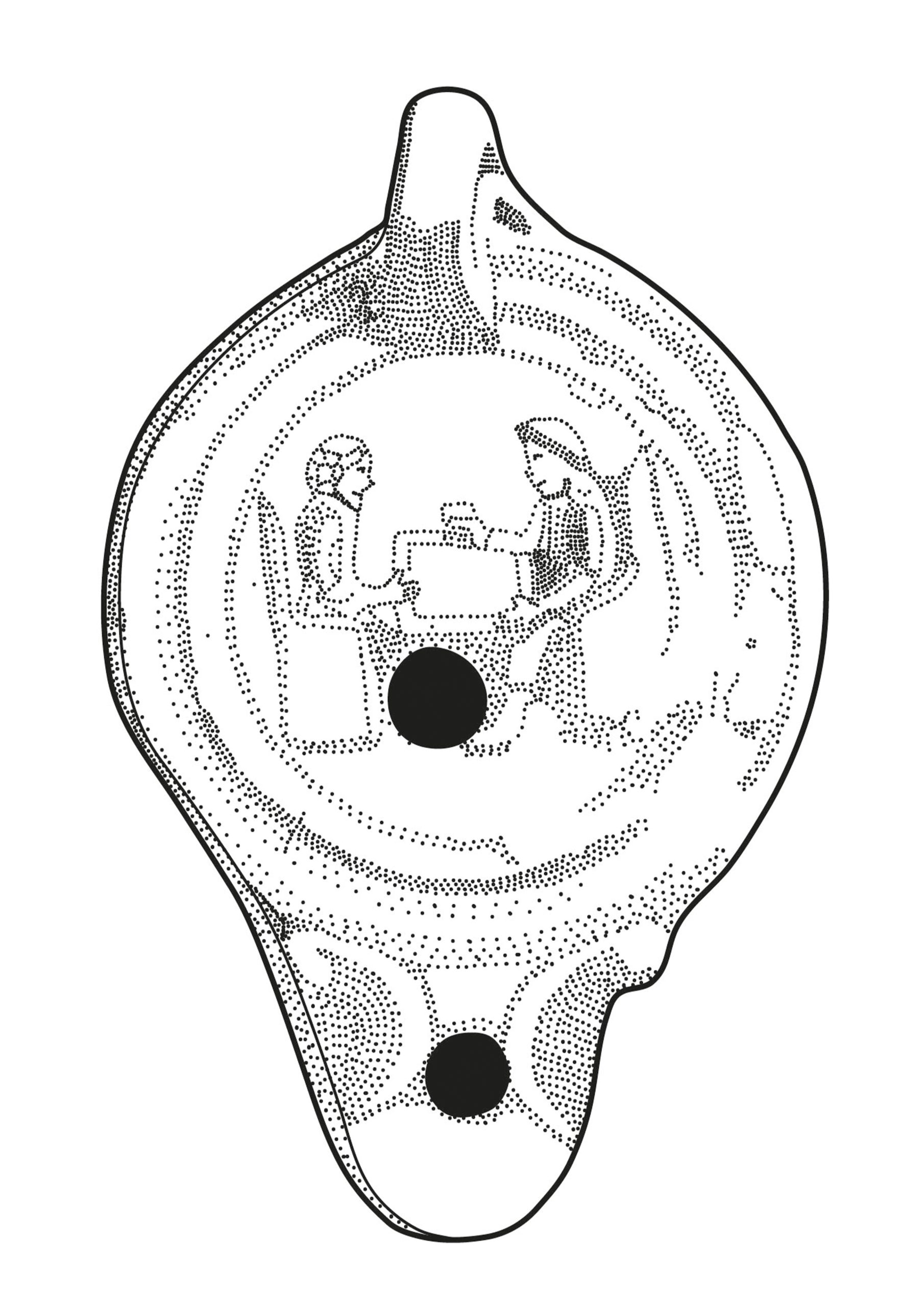

Lamp

Drawing of Roman lamp showing two people playing an unknown game. Köln, Römisch-Germanisches Museum, inv. WO 853. Drawing by Summer Courts.

Ure

Reproduction of Roman marble funerary urn, showing two figures playing latrunculin. Cabinet des Monnaies, médailles et antiques, Paris, inv.54-LAT.49. Drawing by Juliette Quatre.

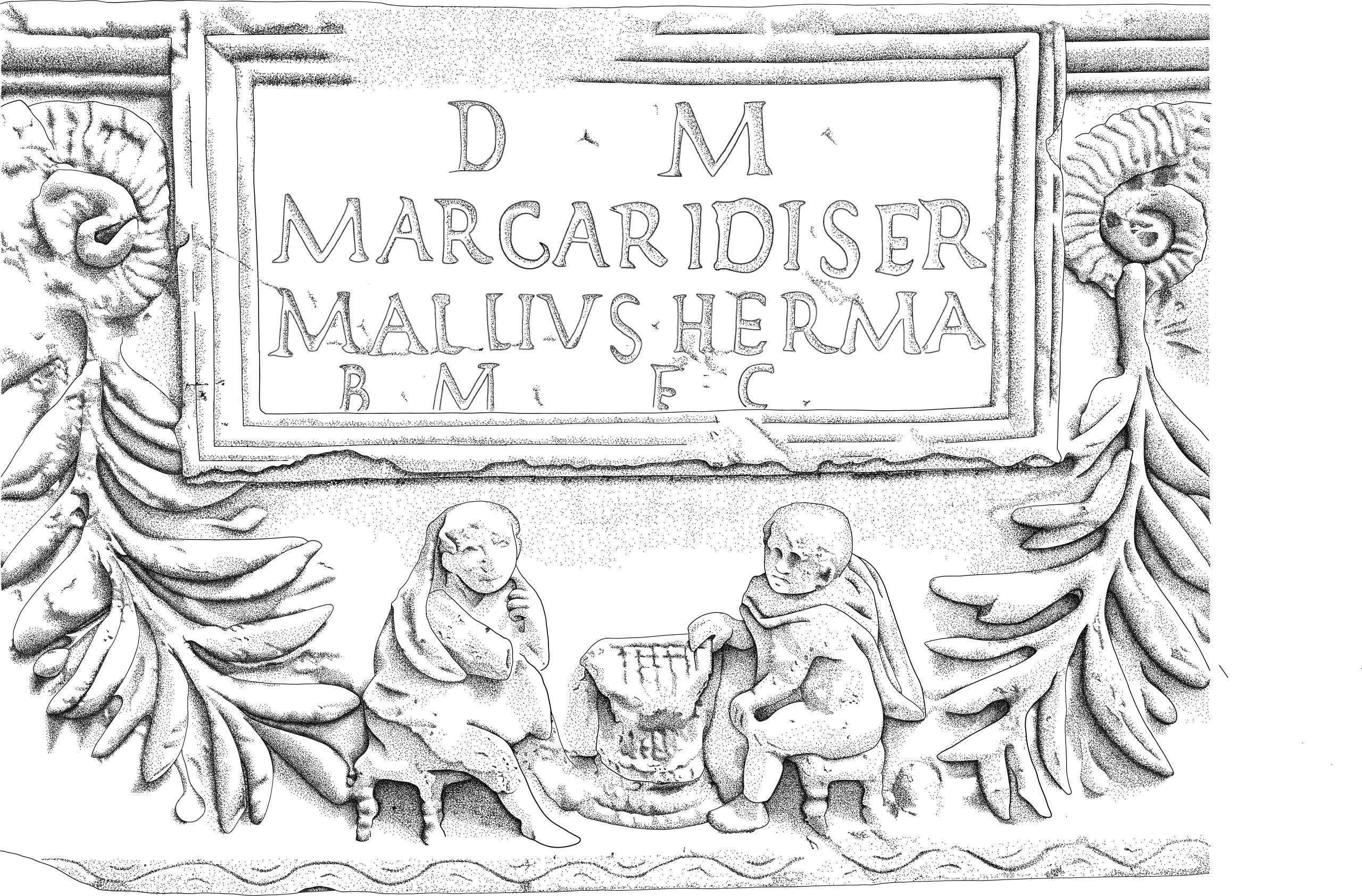

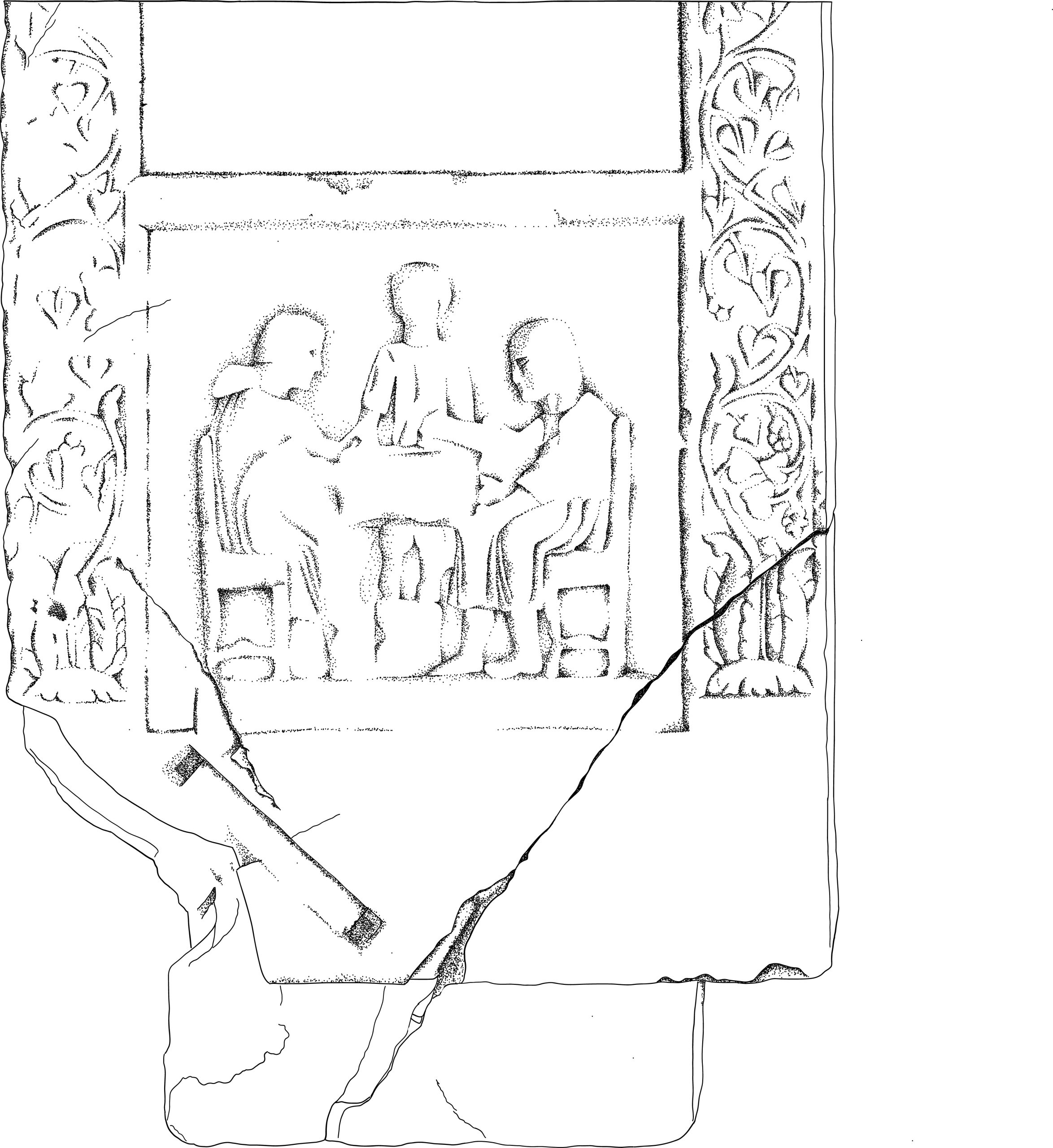

Stele

Reproduction of Roman marble funerary stele, showing two people playing a boardgame was an onlooker. Acqui Terme, Archaeological Museum, inv. 454. Drawing by Juliette Quatre.