Decadent Feminism: ‘New Woman’ Writers in the Special Collections

This is the first of two blog posts written by Helen Zeineh as part of a Undergraduate Research Opportunities Programme (UROP) project undertaken in the summer of 2022. Feminism’s debt to nineteenth-century decadence, and women’s contributions to decadence, are rarely acknowledged. This project sought to address this by cataloguing and publicising the University of Reading’s rare book resources relating to the ‘female decadents’, better known as the ‘New Woman’ writers of the 1890s.

The UROP project, ‘Decadent Feminism’, was supervised by Dr. John Scholar from the Department of English Literature, University of Reading and Fiona Melhuish, UMASCS Librarian, University of Reading Special Collections.

‘Withholding education from women was the original sin of man—’

—Sarah Grand, ‘The Heavenly Twins’ (1893)

She smoked cigarettes, rode a bicycle, wore trousers, and wrote scandalous literature—the New Woman was shockingly radical for the 1890s. But the twentieth century saw the New Woman movement and its writers swept under the rug. Their contribution to British Decadence has been almost forgotten, even though New Woman authors experimented with literary form, gender and sexuality just as much as male decadents like Oscar Wilde. Why have these pioneers of literature and feminism been forgotten? New film adaptions of novels, and this UROP project’s catalogue at the University of Reading, are bringing new recognition to these neglected feminists, drawing on publications from the rare book collections at the University of Reading.

Sarah Grand coined the term in 1894, but the New Woman as a phenomenon had been growing since the mid-Victorian period when educational opportunities began to increase for women. A small number of women were now able to participate in higher education in new institutions such as Girton College, Cambridge, founded in 1869. Such education gave New Woman writers a certain level of intellectual freedom.

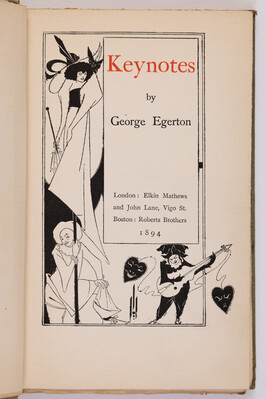

The New Woman also coincided with the fin de siècle literary era, to which the decadents and aesthetes belonged to, and inevitably they overlapped. Decadent dandies like Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley moved in the same literary circles as some New Woman authors, like Vernon Lee (Violet Paget), George Egerton (Mary Chavelita Dunne) and Ella D’Arcy.

The New Woman and the dandy both challenged Victorian gender roles – and being condemned by social commentators made them allies. The New Woman was a ‘Revolting Daughter’, a ‘Wild Woman’—not meek and timid as the traditional Victorian woman. She spoke her political views out loud, and that forthrightness was mocked in magazines like Punch. Similarly, the dandy’s intense focus on beauty and physical appearance was construed as a sign of his effeminacy or homosexuality.

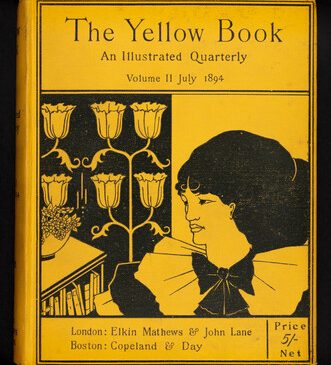

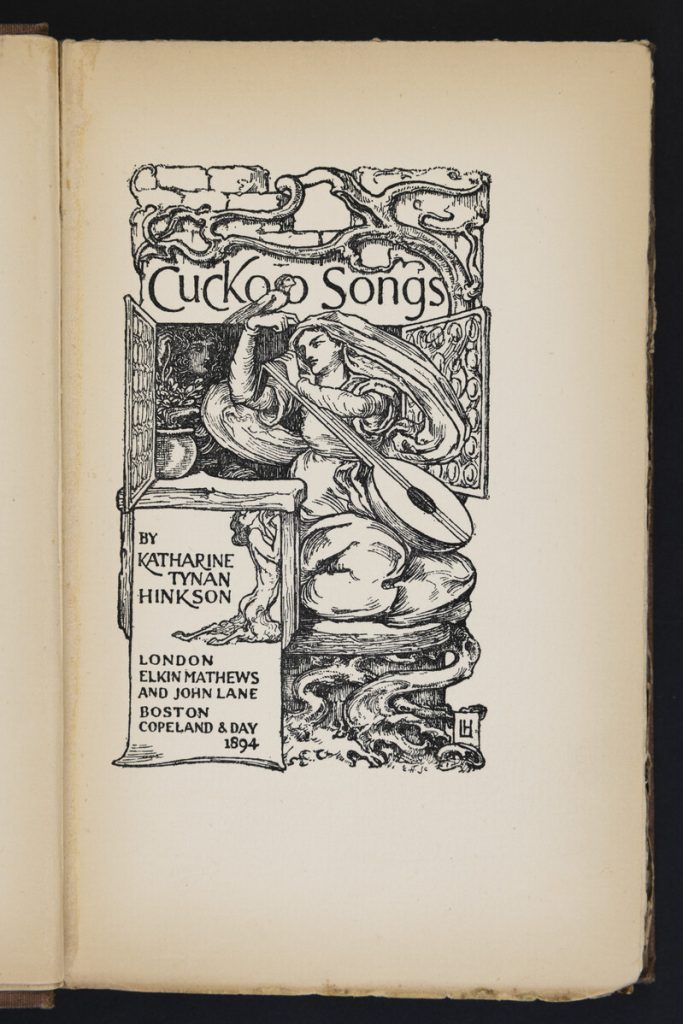

Some women sent their works into decadent publications such as The Yellow Book. Its publishers, John Lane and Charles Elkin Mathews, welcomed such submissions and published many New Woman works. Some books were only printed 100-500 times, however, which greatly limited their longevity after the New Woman era.

It’s clear what the Victorians thought of the New Woman. In Dracula (1897), Bram Stoker shows two extremes of the New Woman, one praised and one punished. Lucy Westenra is punished for her deviant desires (wishing she could have three husbands) by being turned into a vampire. Mina Harker, meanwhile, is a dutiful wife to Jonathan, and gets to live. Though she is certainly modern, working as a secretary and learning the invaluable skill of typewriting, it is only so that she may be useful to her husband.

Sarah Grand’s essay, ‘The New Aspect of the Woman Question’ (1894), describes the New Woman as in ‘silent contemplation… until at last she solved the problem’.1 Said ‘problem’ was the puzzle of women’s inferiority. Women, in Grand’s view, apparently allowed men to build a patriarchal society and oppress them under it. Grand’s New Woman doesn’t have any specific qualities, just a superior intellectual air about her, endlessly patient with her inferiors, a saviour to a broken world. In Grand’s stories, her female characters take charge of their own lives, such as Evadne in The Heavenly Twins (1893), who effectively disowns her husband after finding out he has syphilis.

Grand’s position wasn’t shared by everyone. Ouida (Maria Louise Ramé), wrote an article in Punch in 1894 criticising the New Woman, and her unwillingness to share the ‘remedy’ for women’s suffering. She pokes fun at Grand’s idea that women ‘graciously refrained from preventing’2 the patriarchy. Instead of ‘stealing’ men’s artistic techniques, trying to fit into a space not made for them, Ouida argues that women should establish their own original kind of art. She insists that instead of following the New Woman, trying to be equal to men, women need to ‘till’ their own domestic sphere to produce better children, and to create art from there. Victorian society was also eager to reduce women to their domestic setting instead of allowing them to venture out into politics.

It isn’t hard to find flaws in the ideal of the New Woman. Most of these writers were middle- to upper-class women, who could afford to self-publish their works. Higher education was also only an option for the wealthy, so the emancipation some writers were preaching (such as Sarah Grand’s emphasis on the middle-class woman) was unattainable for most women. To be fair, decadence also required a degree of wealth, as living a life leisurely enough to appreciate art and beauty required disposable income and spare time. Ouida disdainfully reminds us of Grand’s ‘Scum-woman’ and ‘Cow-woman’,3, who were left behind by the New Woman, not able to achieve her enlightenment. Grand’s characterisation of ordinary women is certainly patronising, and the New Woman was viewed by many as a condescending snob.

Some New Women had very controversial views; Olive Custance published works in her husband’s right-wing and anti-Semitic journal Plain English. E. Nesbit gave a speech entitled ‘Natural Disabilities of Women’ against emancipation. Some, however, were activists for marginalised people. Olive Schreiner, a South African writer, was an advocate for Black, indigenous, and Jewish South Africans. Mona Caird was active in the women’s suffrage and animal rights movement and Sarah Grand was an activist for prostitutes and for sexual education.

So, the definition of a New Woman is murky, without a core of political and social convictions. However, literary historian Carolyn Christensen Nelson argues that they shared ‘a rejection of the culturally defined feminine role and a desire for increased educational and career opportunities that would allow them to be self-sufficient’.4 Women were now allowed to hold on to property after marriage, and so able to live independently. For example, the two authors who were ‘Michael Field’, Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper, lived together as a lesbian couple with money inherited from Bradley’s father.

Not all New Women were opposed to marriage, but they agreed that women should choose to marry rather than be forced to. Marriage is of course related to sexuality, and while Grand advocated for the sexual purity of both men and women, writers like Egerton and Lee celebrated women’s sexuality, portraying women who lived unconstrained lives, similar to their own, which included relationships with other women.

As the twentieth century progressed, fewer New Woman works remained in print, and modernism delivered a mortal blow. Perhaps the once shocking New Woman views paled in comparison to modernists’ new radical opinions on art and politics, and indeed the suffragettes were moving beyond the New Woman’s politics.

Some authors, such as ‘Lucilla’, remain only a pseudonym, with nothing but their works to give us any clue to their identities. Some New Woman writers, however, left behind indubitable legacies; E. Nesbit’s children’s stories remain celebrated, particularly The Railway Children, a new film version of which was in cinemas this summer (The Railway Children Return). Hopefully with new catalogues of collections, institutions like the University of Reading can bring the New Woman, smoking and cycling, back into the light 130 years later, letting her claim her place amongst other literary and feminist pioneers.

Key designs with the monograms of the writers Marie Clothilde Balfour and Florence Henniker from books by them in the Reserve Collection published by John Lane.

A second blog post, to be published here shortly, will examine the lives and work of five New Woman writers in more detail.

A catalogue bringing together the rare book material relating to the New Woman movement in the University of Reading collections was produced as part of the project as an aid for researchers and students, and is available to view here.

A hard copy version will also available in the Reference collection at the University of Reading Special Collections Service.

References

1 Sarah Grand, ‘A New Aspect to the Woman Question’ in A New Woman Reader: Fiction, Articles and Drama of the 1890s, ed. Carolyn Christensen Nelson (Broadview Press Ltd., 2001) p.142

2 Ouida, ‘The New Woman’ in A New Woman Reader: Fiction, Articles and Drama of the 1890s, ed. Carolyn Christensen Nelson (Broadview Press Ltd., 2001) p.154

3 Ouida, p.157

4 Carolyn Christensen Nelson, p.x