The New Woman: Five Women Writers of the 1890s

This is the second of two blog posts written by Helen Zeineh as part of a Undergraduate Research Opportunities Programme (UROP) project undertaken in the summer of 2022. This post explores the lives and work of five notable ‘New Woman’ writers of the 1890s.

The UROP project, ‘Decadent Feminism’, was supervised by Dr. John Scholar from the Department of English Literature, University of Reading and Fiona Melhuish, UMASCS Librarian, University of Reading Special Collections.

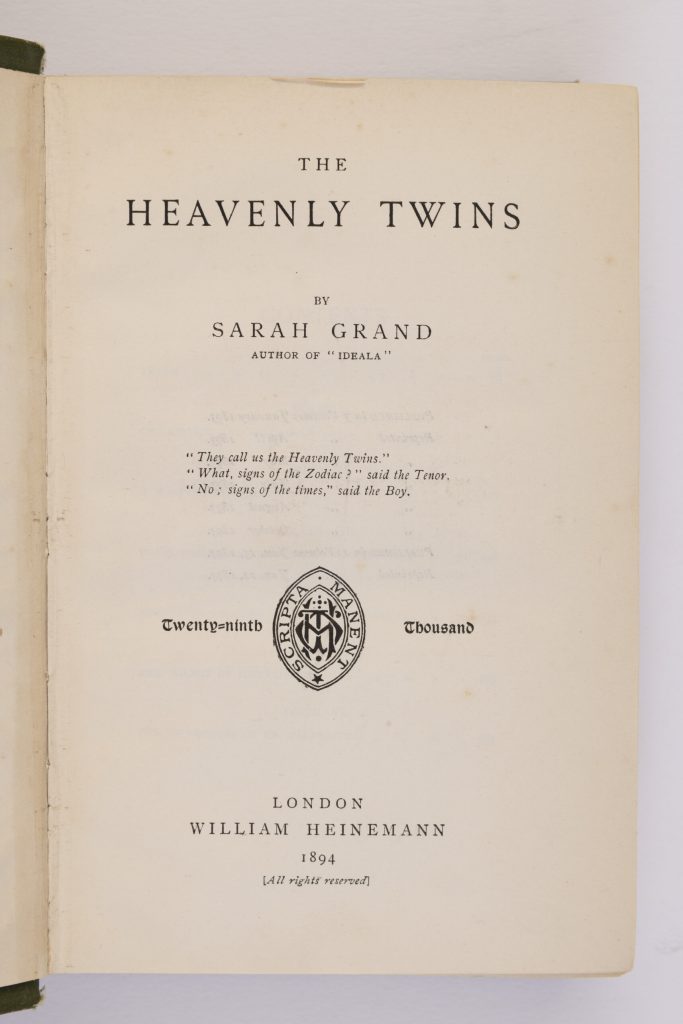

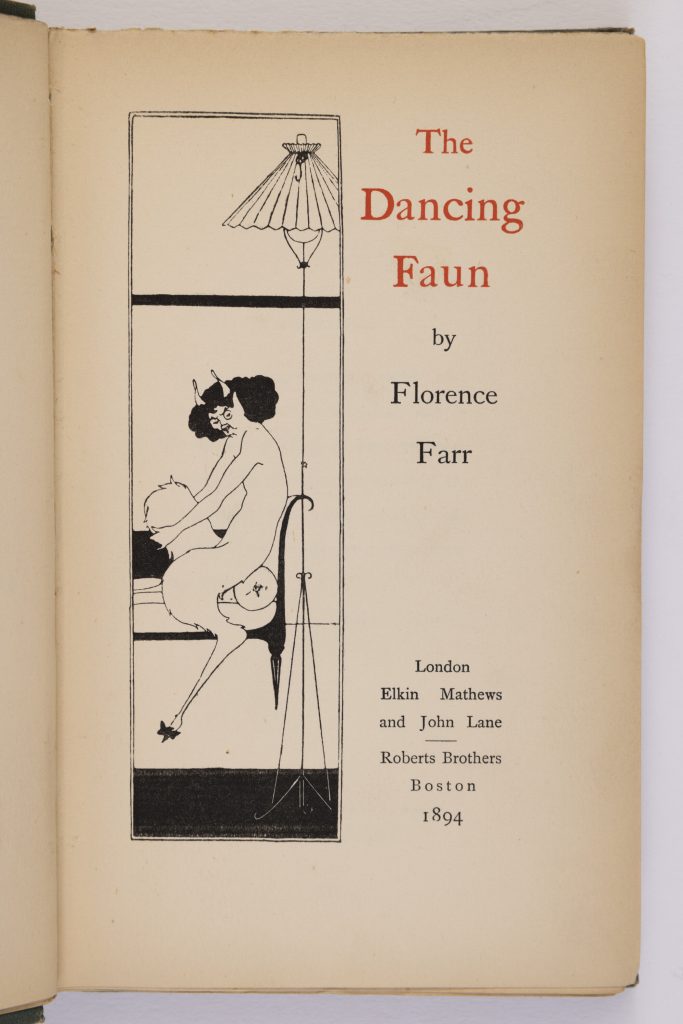

The New Woman—cigarette-smoking, bicycle-riding, trouser-wearing—shocked the Victorians in the 1890s. Sarah Grand coined the term in 1894, but the New Woman phenomenon had been growing since the mid-Victorian period, with female authors who were eager to prove themselves worthy of literary fame. Titles include Michael Field’s Attila My Attila, Sarah Grand’s The Heavenly Twins, George Egerton’s Discords, and Florence Farr’s The Dancing Faun.

The New Woman also coincided with the fin de siècle literary era, to which the decadents and aesthetes also belonged. Decadent dandies like Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley moved in the same literary circles as some New Woman authors such as Vernon Lee (Violet Paget), George Egerton (Mary Chavelita Dunne) and Ella D’Arcy.

As a genre, the New Woman is harder to pin down, but most authors incorporated social commentary into their works, often from pre-suffrage feminist or socialist viewpoints. New reforms meant women could enter university and retain property, improving their intellectual and economic positions.

Sadly, many New Women vanished into history, the only hint of their existence a short poem or a never-revealed pseudonym. Collections such as the one at the University of Reading offer opportunities to renew interest in these authors, housing rare books only printed 500 or even 100 times. Some New Women, however, made enough of an impact in their time that their legacies still live today.

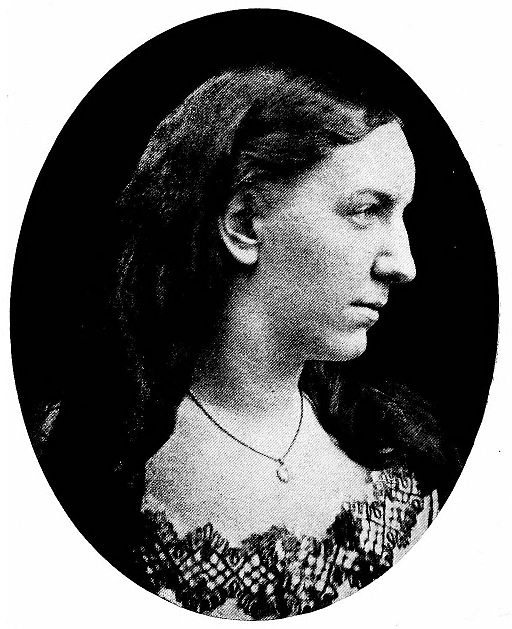

Sarah Grand (1854–1943) – feminist writer

Sarah Grand was a political activist from her youth, being expelled from school in 1868 for protesting against the Contagious Diseases Act. Her first novel Ideala (1888), about a woman struggling with wanting to leave her unfaithful husband, helped Grand to leave her husband in 1890 and relocate to London. The Heavenly Twins (1894) included Grand’s opinions on marriage and women’s rights: the protagonist distances herself from her husband after discovering he has syphilis from extra-marital sex. She renamed herself ‘Sarah Grand’ with its publication, choosing a feminine pseudonym, instead of a more acceptable male one, which reflected her political views and her drive towards women’s emancipation.

Her essay in North American Review, ‘The New Aspect of the Woman Question’ (1894), established the ‘New Woman’, naming a movement slowly growing over the century. For Grand, the movement’s aim was to give women a political voice and question societal status quos, like marriage. In The Heavenly Twins, Grand points out the danger of unequal moral standards for men and women, advocating sexual purity in both genders. Grand was mostly interested in her subject matter of social problems, making her ideas accessible to other women.

Grand lectured on women’s issues in America and England. During World War II, she moved to Wiltshire, where she died in 1943.

‘Ouida’ (Maria Louise Ramé) (1839–1908) – author, critic, activist

Maria Louise Ramé’s pseudonym ‘Ouida’ came from her childish pronunciation of ‘Louise’. In 1859, after moving to London, Ouida’s stories were serialised in magazines like Bentley’s, in which her neutral pseudonym and scandalous stories intrigued readers. She moved into the Langham Hotel in 1867 and dived headfirst into London Bohemia; she threw luxurious soirées with guests, including Oscar Wilde, serving as character inspiration.

Primarily an essayist, Ouida wrote about social and literary issues, but her novels and children’s stories earned her a living. Artists in all media inspired her and she combined romanticism and social criticism. She commented on issues like women’s suffrage, religion and animal rights, denouncing animal experimentation (‘The New Priesthood: A Protest Against Vivisection’ (1893)).

Views and Opinions (1895) discussed her position on issues including the New Woman. Ouida satirised Grand’s essay, criticising the New Woman’s supposed superiority to the ‘Scum-woman’ and ‘Cow-woman’ that Grand had identified. Ouida directed women to consider their ‘immense fields of culture untilled’—how women can shape a better society through their children’s upbringing.

After her mother’s death in 1893, Ouida fell into poverty. Losing her copyrights and several instances of misfortune made her accept a British Government pension of £150 a year in 1906. She died in 1908 of pneumonia, in Viareggio, Italy.

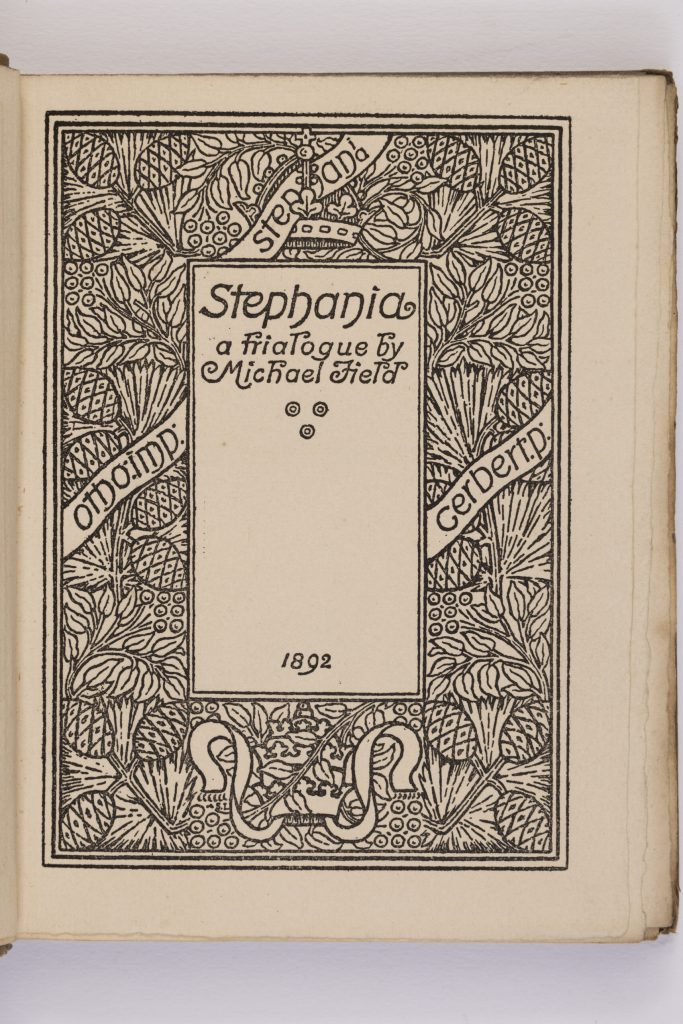

‘Michael Field’ (Katherine Bradley (1846–1914), Edith Cooper (1862–1913)) – poet, author, playwright

‘Michael Field’ was an aunt and niece duo, Katherine Bradley and Edith Emma Cooper. In the late 1870s, the two became lovers, beginning a 40-year creative and romantic relationship. Their first publication as ‘Michael Field’ was the critically successful drama Callirrhoe and Fair Rosamund (1884). Bradley’s inheritance made the two financially independent, and the two bought a house after Cooper’s father died in 1899.

They were aesthetes, influenced by Walter Pater’s work, with a large circle of friends including Oscar Wilde, Robert Browning, and the partnership Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon. Ricketts and Shannon designed many covers for Michael Field’s works.

The revelation of Michael Field’s identity damaged their critical success. Nevertheless, they kept writing, becoming fin-de-siècle celebrities with a small but influential audience. Many works were erotic love poems to each other, and their joint pseudonym cemented their relationship.

Catholicism and the Renaissance influenced them, including Sappho’s poetry, a basis for poems and plays including Long Ago (1889). Although part of the New Woman era, especially as women writing sensual and explicit work, the Fields were dismissive of women and the working class, possibly a reflection of their mostly male literary circle and inherited affluence.

Both died of cancer, Cooper in 1913 and Bradley in 1914.

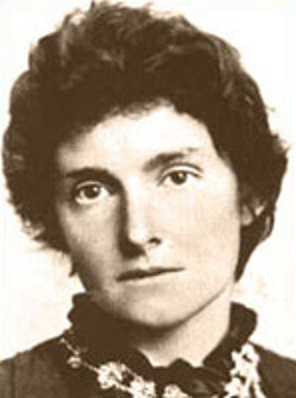

Florence Farr (1860–1917) – author, actress, director, occultist

Florence Farr’s father advocated for women’s education and professional rights, influencing Farr’s lifelong philosophy. Post-education, Farr became an actress, enjoying moderate success in the West End. She married actor Edward Emery in 1884. He left for an American tour in 1888, and didn’t return, and she obtained a divorce in 1895.

She became involved in the New Woman movement when she moved to Bedford Park in West London, where women had philosophical discussions equally with men. Farr started publishing her writing, her first novel The Dancing Faun in 1894. She befriended W.B. Yeats and George Bernard Shaw, performing Yeats’ poetry, and starring in Shaw’s plays, like Widowers’ Houses (1892). She starred in Henrik Ibsen’s Rosmersholm (1891), portraying a New Woman.

She was side-tracked from theatre in 1890 by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an occult society. She led classes in tarot, scrying and Enochian magic. She wrote philosophical papers, like ‘A Short Inquiry Concerning the Hermetic Art by a Lover of Philalethes’ (1894). In 1901, Farr collaborated in producing two one-act plays recounting Egyptian mythology, a keen interest of hers. Personal disputes disillusioned her, and she resigned in 1902.

She toured theatre in Europe and America, writing many non-fiction articles. In ‘Our Evil Stars’ (1907), Farr encourages women to ‘kill the force in us that says we cannot become all we desire’ to improve society for women. She took up a teaching post at the Uduvil Ramanathan Girls College in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1912.

In 1916 she was diagnosed with breast cancer, and she died in Colombo, Sri Lanka in 1917.

Edith Nesbit (1858–1924) – author, poet, activist

Edith Nesbit was born in Kennington, Surrey. The family moved around Europe due to their daughter Mary’s ill health, and settled in Halstead after her death, the location inspiring The Railway Children (1905).

In 1880, seven months pregnant, Nesbit married Hubert Bland. The marriage was tumultuous; Bland impregnated two women, including Nesbit’s friend Alice Hoatson, though Nesbit adopted the children she bore. The couple joined the Fabian Society, an organisation dedicated to democratic socialism. Nesbit wrote on socialism and poverty, but did not apparently support women’s suffrage, once giving a speech called ‘Natural Disabilities of Women’ to the Fabian Women’s Group.

She published around 40 children’s books, much of her fiction focusing on groups of children, like the Bastables of The Story of the Treasure Seekers (1899). Her locations were inspired by her beloved countryside, especially Kent. Nesbit is cited as creating modern children’s fantasy, her famous works include The Railway Children (1905) and The Wouldbegoods (1901). Her work was so highly admired, Alfred Miles included her in Poets And Poetry Of The Century (1891) alongside Oscar Wilde, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Rudyard Kipling.

Despite Nesbit’s dismissal of emancipation, her books often portrayed mothers working in the background, as in The Railway Children. She also engaged with the Gothic: her short story The Shadow (1905) discusses middle-class husband’s control of their wives and the danger of sexual inequality.

After her husband’s death, Nesbit married Thomas Tucker in 1917, a boat captain. They moved to New Romney in Kent, where she lived until her death in 1924.