A cabinet of curiosities : Ole Worm’s ‘Museum Wormianum’ (1655)

Written by Fiona Melhuish, UMASCS Librarian

The history of public museums is also a history of private collectors and collecting, as many of the world’s oldest museums began as the personal collections of wealthy individuals and families. Some of these collections took the form of ‘cabinets of curiosities’ (also known in German as wunderkammer or wonder-rooms), which became popular from the sixteenth century. The word ‘cabinet’ originally meant a room rather than a piece of furniture. These collections were precursors of the modern museum, containing eclectic and exotic objects from around the world, obtained through the growing foreign trade market and from the building of colonial empires. Many collectors sought to celebrate the glory and variety of God’s creation and the creative skill of man by collecting objects of beauty and wonder.

One of the most famous ‘cabinets of curiosities’ was created by Ole Worm (pronounced “Vorm”) (1588-1654), a Danish physician and polymath. Worm was born in Aarhus in Denmark where his father served as mayor. Worm embarked on a ‘grand tour’ of Europe in 1605, and visited many museums and collections. During this time, Worm began to collect objects of interest, and on his return, he continued his collecting with the help of other European collectors. Worm gathered a wide range of different types of artefact from the natural world such as bones, rocks and minerals, and stuffed animals and birds, together with man-made artefacts and antiquities, including Roman jewellery, tools and scientific instruments.

Worm attended various European universities before receiving a doctorate in medicine at Basel in 1611. He became professor of humanities at the University of Copenhagen, and later, professor of medicine in 1624, and also served as the personal physician to King Christian IV of Denmark. In the light of the current Covid-19 situation, it is rather topical to note that Worm remained in Copenhagen to treat and care for his patients during epidemics after many others had fled the city. Unfortunately he caught the plague during the epidemic of 1654 and died in Copenhagen that year.

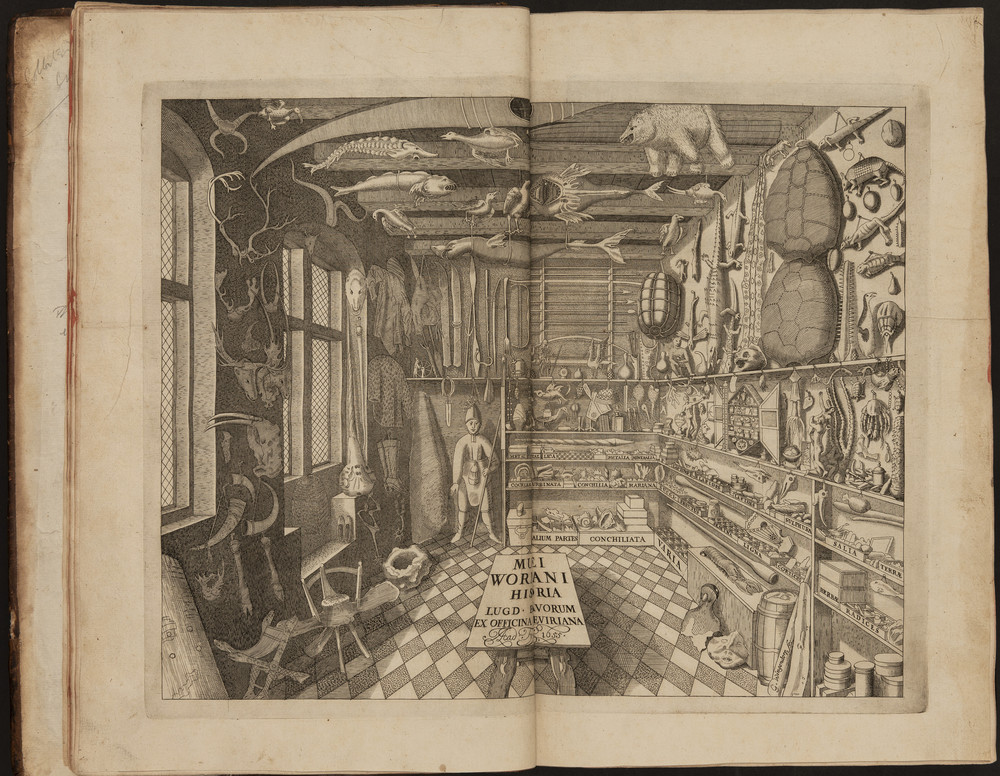

Worm produced two earlier inventories of his collection, but the most well-known and most complete catalogue of the collection was edited and published posthumously by his son, William in 1655. This publication was entitled Museum Wormianum : seu historia rerum rariorum … (‘Worm’s Museum. Or a history of rare things…’ ). The frontispiece of the book is a large fold-out engraving of Worm’s museum in his home [see image above], showing the objects in all their fascinating, and sometimes quirky, detail. The illustrated catalogue entries are divided into four books, the first three dealing with minerals, plants and animals. The fourth book describes the man-made objects or artificialia, such as the archaeological artefacts, coins and some works of art. Worm’s catalogue is also an important reference work, with information relating to the theories of other writers. Humans are classified in the ‘animals’ section, together with ‘divine monstrosities’, including deformed fetuses and the ‘giant’ skull. There are some strange inconsistencies though as mummies are classified as ‘minerals’, even though they are human remains.

Through his collecting and research, Worm was be influential in many disciplines including archaeology, museology and ethnography. Worm encouraged his students to make observations and discoveries about the curious objects in his collection through direct handling and study of the objects themselves, rather than relying on myth or the theories of earlier writers. He wrote in a letter that he aimed to “present my audience with the things themselves to touch with their own hands and to see with their own eyes, so that they may themselves … acquire a more intimate knowledge of them all” – similar to the collections-based teaching and learning that we practice at the University of Reading today using our own collections, especially with students studying our museum studies modules.

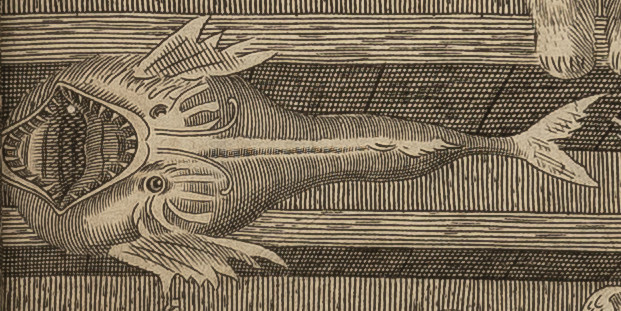

Worm’s method of scientific enquiry was a kind of proto-empiricism – gaining knowledge through direct study of an object – and a modern approach that was still quite new to Worm and his contemporaries. His direct study of objects led him to make groundbreaking discoveries that disproved a number of beliefs about natural phenomena, including the myth of the existence of unicorns. Worm had a supposed ‘unicorn horn’ in his collection [see image below], but was sceptical about its origins, given that he had never seen a horn attached to a unicorn skull. However, in 1638 he was able to prove that these horns were actually tusks from narwhals, a type of whale, showing the pointed “horn” still attached to its whale skull. However, there are some ‘mythical’ specimens in the collection whose true identification appear to have eluded him, such as a ‘giant’s’ skull. Worm was also unable to correctly identify the Stone Age tools in his collection, and, in keeping with popular belief, he classified them as “Cerauniae, so called because they are thought to fall to earth in flashes of lightning”.

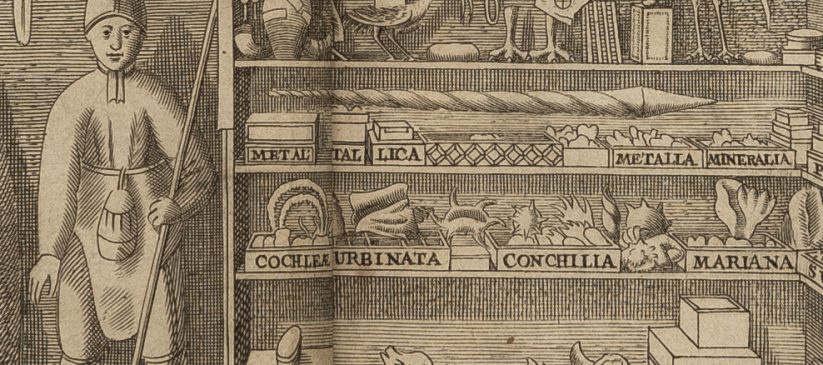

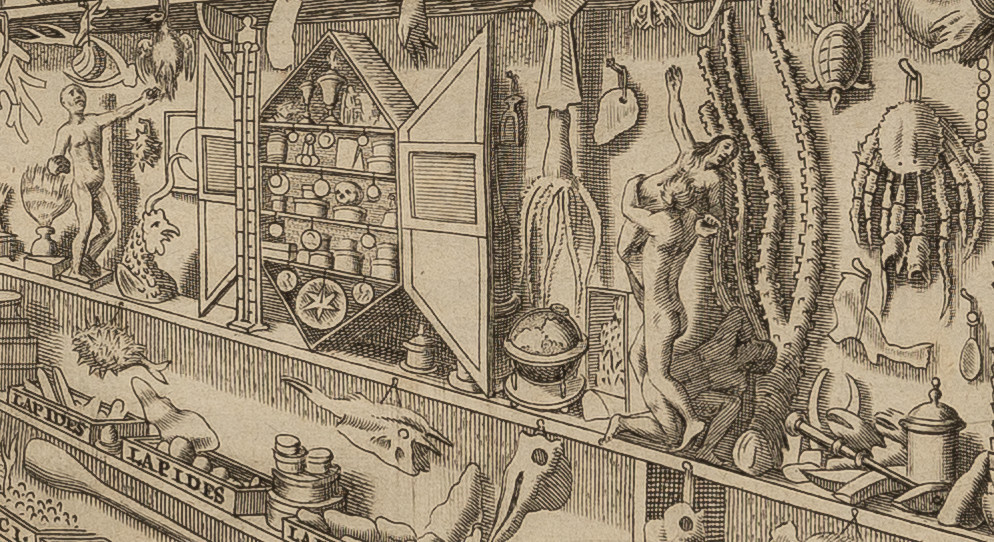

One of the most fascinating aspects of the catalogue is Worm’s organisation and classification of his artefacts, which is as interesting as the objects themselves. In the engraving, objects have been organised into boxes with labels [see image above] such as Lapides (stones), Salia (salts) and Terme (earths), classifications which follow conventional seventeenth-century taxonomies. For seventeenth century collectors, the category “stones” included fossils, but also fruit stones, and the term “fossils” referred to any object that had been dug out of the ground, including bits of pottery and other archaeological artefacts.

The manner in which Worm chose to display his objects as shown in the frontispiece (although we do not know if this is an accurate representation) is also of interest. However, the arrangement of the artefacts on the shelves seems rather random compared with modern museums, with man-made artefacts arranged alongside natural history specimens [see image above]. One of the many curious items is a humanoid automata, which, when operated by a hidden wheel, could move around and pick up objects. The figure is dressed in what was thought to be native American costume.

After Worm’s death, his collection was purchased by Frederik III, king of Denmark and a museum was built to house the collection which was open to the public for an admission fee. Items such as a bronze dagger and an Icelandic drinking horn still survive in the royal collection, and about forty objects are on display at the Natural History Museum of Denmark. In 2004-5, the artist Rosamond Purcell created an extraordinary installation which recreated the engraving of Worm’s museum. This installation is now permanently housed at the Geological Museum at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

We are fortunate to have two copies of Worm’s catalogue in the Cole Library: one published in Leiden by Jean Elzevir (COLE–092F/01) and the other published in Amsterdam by Louis and Daniel Elzevir (COLE–092F/16); two of the three editions of this work that were published, all printed in 1655, by different members of the Elzevir family. The Elzevirs were a Dutch family of booksellers, publishers, and printers of the 17th and early 18th centuries, and were celebrated for their fine printing, use of high quality paper and a clear, elegant typeface.

To explore more of the treasures of the Cole Library, take a look at our new online exhibition.

References and further reading

Byrnes, Laurel. Ole Worm’s Cabinet of Wonder: Natural Specimens and Wondrous Monsters. https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2017/05/ole-worms-cabinet-of-wonder-natural-specimens-and-wondrous-monsters.html [Accessed 4 May 2020]

Hoskin, Dawn. Born on This Day: Ole Worm – collector extraordinaire. https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/creating-new-europe-1600-1800-galleries/born-on-this-day-ole-worm-collector-extraordinaire [Accessed 6 May 2020]

McQuillian, Kate. Image of the month: Worm’s cabinet of curiosities. https://www.stgeorges-windsor.org/image_of_the_month/worms-cabinet-curiosities/ [Accessed 6 May 2020]

Meier, Allison. Ole Worm Returns: An Iconic 17th Century Curiosity Cabinet is Obsessively Recreated. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/ole-worm-cabinet [Accessed 4 May 2020].

Purcell, Rosamond. A Room Revisited. Natural History, Vol. 113, Iss. 7, (Sep 2004): 46-48

Richards, Sabrina. The World in a Cabinet, 1600s. The Scientist, Vol. 26, Iss. 4, (Apr 2012): 88,11.

Worm, Ole (or Olaus Wormius). Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, vol. 14, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2008, p. 505. Gale eBooks, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2830904723/GVRL?u=rdg&sid=GVRL&xid=349b3a3e. [Accessed 5 May 2020].

2 thoughts on “A cabinet of curiosities : Ole Worm’s ‘Museum Wormianum’ (1655)”