Gustav Holst: teaching and performing music

Gustav Holst’s Music Scholarship Pupils at University College, Reading 1920–1923: Part 2

Written by Philippa Tudor who researches and writes about previously unexplored aspects of the life and work of Gustav Holst and his family. She is the author of a 2015 biography of Holst’s wife Isobel.

Holst’s teaching methods

Holst’s first scholarship pupil Edmund Rubbra was 19 when he became Holst’s pupil at Reading and had needed to leave school to start full-time work at the age of 14. He described how Holst put him at his ease by taking him on walks and encouraged him to read widely, for example sharing his own enthusiasm for the works of Joseph Conrad.[1]

“It was characteristic of Holst that my first lesson with him should have taken the form of a walk and talk in which, if I remember rightly, music was but incidentally touched upon. In this way he accomplished in one meeting what perhaps only months of lessons with eyes poring over manuscript paper could have done: that is, he succeeded in setting me at ease, and giving me the feeling of companionship, rather than the sterner and less fruitful relationship of the usual master and pupil. Not only was I set immediately at ease, but I was also made to feel that my attempts at composition and the thoughts about music that I had formulated secretly and half-ashamedly in my mind were important enough to be treated seriously. This was brought about not by flattery – a species of insincerity utterly foreign to Holst – but by a sympathetic perception of the difficulties which a growing mind is constantly meeting.” [2]

Holst’s own composition practice involved repeated experimentation – he often referred to producing large quantities of waste paper. He was, however, keen to spare his pupils the stress from which he suffered periodically for much of his life. This may have been particularly true of the prolific composer Edmund Rubbra, who noted with appreciation:

“Holst never insisted that the pupil should bring fresh work at each lesson. The pupil was therefore freed from the strain and anxiety of forcing out unfelt ideas. If no original work was forthcoming, then the lesson could be spent in any number of delightful and profitable ways, for Holst was never at a loss to show how surprise and delight could be mingled in a lesson.” [3]

Holst’s pupil and friend William Probert-Jones recalled:

“His teaching … was of such a personal and intimate character that any cold-blooded account of his methods would give an entirely wrong impression. Even the word “methods” I feel to be wrong; there was nothing set or formal in his way of teaching, what he set out to do was to draw out of his pupils all that was best in them by any means in his power, and most perhaps by making them “learn by doing.” He was a curious blend of the visionary and the practical—a rare combination indeed. He had a sincere and unbounded love and enthusiasm for all beautiful music and perhaps the secret of his success with his pupils came as much from the joy which he got from music and with which he infected them, as from anything else that he did. He simply radiated a love for music and it was bound to be reflected by those with whom he came into contact. …

But in addition to this immense enthusiasm he possessed a very practical and commonsense outlook. … His composition pupils too were brought up to keep this practical point of view ever before them and were encouraged to write down their ideas in such a way as rendered them easy in performance. I well remember taking the score of a short orchestral work to him, in which I had written a trumpet part which might have been played by Solomon, but hardly by anyone of lesser calibre. Holst very gently said “You will never get this played, you know. Now if you write this trumpet part like this—and this—and just give him a high A here so that it gives him a chance of showing us what he can do …”

His nature was essentially simple and kindly, with an unlimited store of sympathy for the deserving. He had a genius for getting straight to the root of the matter—a characteristic which showed itself in his works. “Padding” or “talking for the sake of talking” was anathema to him; one’s ideas had to be expressed succinctly and must be germane to the subject in hand. This of course implies the possession of ideas; almost his first words to me were to this effect:—”If you have no ideas, I can’t do anything for you; I can only try to bring out what is already inside, I cannot put music into you.” But to those who had music within them and were prepared to work hard his kindliness, patience, sympathy and encouragement were invaluable. In criticism he was rarely harsh but always pointed and the only thing which ever really roused his ire was unworthy work. Then he could be severe ! ! !” [4]

* * * * *

Performing pupils’ compositions

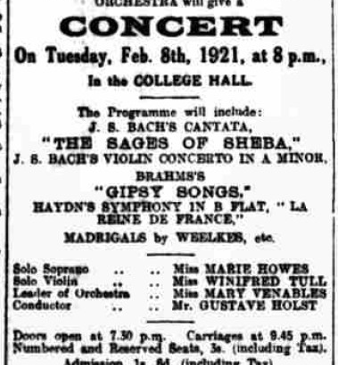

Holst quickly introduced to Reading his practice of including a composition by a pupil in college concerts – a widespread practice today but less so in the early 20th century. For the concert on 8 February 1921 it was by Douglas Clarke, whose “Lament on the Death of a Child” for small orchestra received its first performance. The summer term concert, held in the college hall on 15 June 1921 with Holst conducting, included another first performance by a College pupil, this time Edmund Rubbra’s Tone-Poem “Nature’s Call” for piano and orchestra, with the composer playing the piano solo.[5] The concert on 21 February 1922 featured a first performance of a jig for orchestra by William Probert-Jones, “To be conducted by the Composer”, the programme noted, whilst the rest of the concert was to be conducted by Holst himself. The Jig “was most enthusiastically received”, according to the college reviewer,[6] whilst “Ubique”, the Reading Chronicle reviewer, recorded that the audience was so enthusiastic about Probert-Jones’ Jig that it insisted on its immediate repetition.[7] 20 February 1923 saw the last of the series of concerts at Reading conducted by Holst himself. Allan B. Sly was the solo pianist for the first movement of Bach’s concerto in D minor, and fellow Reading student William Probert-Jones was to conduct the first performance of his orchestral piece “Shirley Wakes”.

At the start of the 1923-24 academic year Probert-Jones succeeded Holst as conductor of the college orchestra – which Holst had built up rapidly – and choral society. After his former teacher’s untimely death in 1934 Probert-Jones wrote a long appreciation of him, including the following list of Holst’s Reading pupils. R. J. M Brind, D. W. Clarke, Florence L. Gates, Helen G. Manning, Walter C. H. Pearse, W. Probert-Jones, A. T. E. Rogers, C. E. Rubbra, Evelyn A. Sharp, Allan B. Sly. In researching Holst’s teaching of music at Reading, the success of all his scholarship pupils is striking, and all the more so since they were starting their professional careers in the aftermath of the First World War, at a time when the economic depression was looming. The following short biographies illustrate this.

Where shown all images are reproduced with permission. In some cases, it has not been possible to trace the copyright owner. All images are used in good faith and will be taken down if found to have inadvertently breached copyright.

[1] Edmund Rubbra, Gustav Holst: Collected Essays, ed. Stephen Lloyd and Edmund Rubbra (Triad Press, London, 1974), p 17.

[2] Rubbra, Gustav Holst: Collected Essays, pp 40–41.

[3] Rubbra, Gustav Holst: Collected Essays, p 42.

[4] William Probert-Jones, “Gustav Holst”, Tamesis (33: 2) Lent 1935, pp 59–60.

[5] Tamesis, xx, Summer Term, 1921, no. 3, pp 88–89.

[6] Tamesis, xxi, Lent Term, 1922, no. 2, p 67.

[7] Reading Chronicle, “College Concert: Gustav Holst conducts: Jig by Mr. Probert Jones”. Similarly positive reviews were printed in the Reading Mercury, 25 February 1922, and the Reading Observer, 4 March 1922.