Queering the Ure – A trail curated by Domenica Taverna (UoR student)

Queering the Ure is a research project that develops from the awareness that ancient myths evidence the attraction ancient gods and goddesses, as well as mortals, felt towards men and women alike, without shying away from explicit mention of erotic desire. Other stories addressed non-binary identities while intersecting with race and disability. Although the Ure Museum has been a strong LGBTQ+ ally, we aim to be permanently involved with the queer local community in our endeavour to become more inclusive, diverse and accessible.

Representations of these myths and other relevant material can be found in the Ure Museum collections and archives, which can help visitors, students and scholars to engage with the wide scope of experiences of gender and sexuality. Such an approach is in line with the educational programme of the Ure Museum, closely linked to active learning with objects, namely pedagogies that see artefacts as a tool to interact with the visitor. Our collections can be used as a way to look at the lives of people from the past and present through conversation, offering the chance to develop empathy and understanding for the other.

Attis figurine

Attis figurines

[Myth & Religion, 10]

These small clay figurines represent Attis (he/his). He is depicted as a shepherd wearing a Phrygian cap, used to denote an Eastern origin in Greek and Roman art. One of them holds a musical instrument called a syrinx or pan-pipes. The travel writer Pausanias tells us that there were many local legends of Attis, describing him as intersex in one form or another. Most intertwine with the myth of Kybele (she/her), the Phrygian goddess of fertility, also known as Agdistis (they/them). Agdistis was a demon who grew from the fallen sperm of Zeus, father of the Olympian gods, and had male and female genitalia (sex organs). The overpowering sexual force was seen as a threat to the gods, who therefore castrated them—cut off only the male organ (phallos)— in hope of diminishing Agdistis’ strength. The blood from Agdistis’ castration fertilised an almond tree, from which Attis (he/his) was born. One day, Attis came across Agdistis (now she/her) and became crazed at the sight of the divinity, castrating himself and cutting away his genitalia. After Agdistis’ forced transition to female, it could be said that in falling in love with Attis, she fell back in love with the part of herself that was stolen; they are reclaiming their own identity. Attis and Agdistis/Kybele are usually represented with musical instruments — in this case the syrinx — as musical rituals played a key role in their cults, favouring emotional and physical release.

Medusa's gaze

Antefix decorated with Medusa

[Myth & Religion 51]

An antefix can be used to cover the end tiles of a roof as decoration, as well as protecting the tiles themselves from environmental factors. The myth of the Gorgon Medusa, whose fearsome face decorates this antefix, has been famously retold in a variety of different forms, making the story of her stoney-glares and snake-hair one of the most prolific in Greek mythology. A rare version of her origin tells that Medusa was once a beautiful woman who found herself caught in the games of the Greek gods and was raped by the sea god Poseidon in the Temple of Athena. Rather than punishing Poseidon, Athena, the goddess of wisdom and much else, transformed Medusa into a monster for her sacrilege, setting her legend into motion. Owing to the victim-blaming nature of Medusa’s transformation, women and queer communities see themselves in Medusa: they choose to take back control of their own identities and sexualities because Medusa’s identity was stripped from her without her consent. The mythical image of Medusa is therefore a projection of the female gaze, in response to the male gaze. This female gaze steers away from male objectification of women and encourages women to reclaim themselves. In ancient Mediterranean societies desire between women was seen to deviate from the norm, posing a potential threat to the male position within the household. Among Lesbian and other communities, therefore, the image of Medusa now indicates ownership of the self, replacing fear and invisibility.

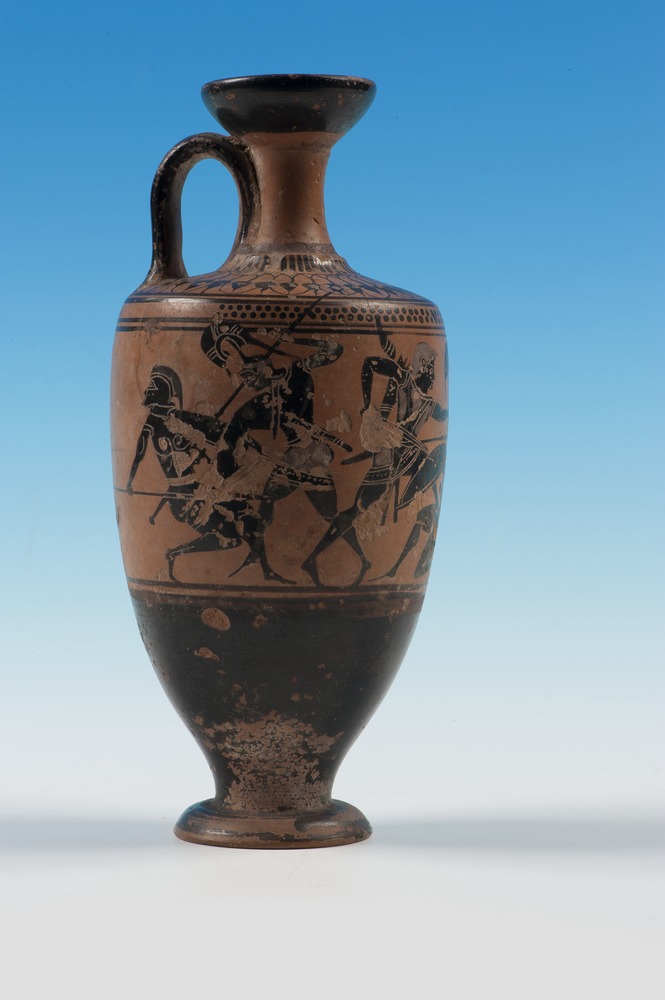

Arming oneself like an Amazon

Arming oneself like an Amazon

[Myth & Religion, 14]

The Amazons fighting Greeks on this lekythos, or oil jar, represent a tribe of female warriors endowed with skill and bravery typically assigned to male Greek warriors. The light-haired man at the centre might be the Greek hero Achilles, shown at the moment he fell in love with the Amazon queen Penthesilea, sadly when he stabbed and killed her. There has been a sense of otherness regarding Amazons, due to their reclusive customs and lifestyles: they lived away from the society of men. Ancient Greeks cast Amazons as foreigners from the East and referred to them with the term barbarian which means ‘people who don’t speak Greek’. Their otherness pits them against Greek men and women alike. Archaeological finds indicate that these mythical women were based on warrior women from central Asia, where men and women were treated with greater equality than in Greece and where women became respected warriors. Women embodying male values challenged the ancient Greeks’ gender constructions. Clearly the Greeks feared women who could hold their own against men. In the 1970s, therefore, lesbians adopted aspects of Amazon identity such as motif of the labrys or double-axe, one of their usual weapons.

Horus' sacred eye

Horus’ sacred eye

[Egypt land of plenty, 5]

Horus, son of the murdered King Osiris, was a protector god in ancient Egypt. This sacred eye represents his ever-watchful eye and is suited to the function of this amulet, which is to protect the wearer. (Nowadays, the eye of Horus in the colours of the rainbow flag and black background symbolises the collective Gay Goths). Horus was subjected to a bisexual power play. After the death of his father, an 80-year power struggle ensued between Horus and his uncle — and murderer — Seth. Tired with formalities, Seth tried his luck at seducing Horus. To Seth’s dismay, Horus’ mother Isis saw through his deceit and saved her son. The power struggle between Horus and Seth captures the role of sex in power-play. As in many myths, sex expressed power rather than love. Interestingly, the tale shows that ancient Egyptian culture didn’t look down on homosexuality — something heroic Horus engaged in himself — so much as it held being subjugated in low esteem. In ancient Egypt there were no sexual taboos or expectations of celibacy or sexual abstinence. Renewal of life was celebrated as an important part of society.

Hermes without borders

Hermes without borders

[The cultural landscape of Greece, 9]

Hermes, who wears a wide-brimmed hat on this kantharos (wine cup) held many roles in antiquity, ranging from messenger of the gods to protector of liminal spaces or boundaries. So he mediated between the living and the dead. This is shown by the bird perched on his right hand: birds were sent from the afterlife to deliver divine messages, so worked together with Hermes. Owing to his liminality, Hermes was popularly invoked on curse tablets, also known as defixiones. These tablets often dealt with relationship troubles: authors would carve their quarrels or desires onto stone, lead, or wax which they then buried, before praying to a chthonic god to fulfil their wish. The subjects of curse-tablets were of all genders and sexualities, emphasising the fact that lovers’ quarrels are boundless.

Dionysos on an amphora

Dionysos on an amphora

[Myth and Religion, 4]

As on this amphora or wine container, Dionysos (god of wine and fertility) usually appears in celebrations, accompanied by female worshippers, called bakchai or maenads, and male satyrs, who look like men with animal ears and tails. Dionysos is sometimes symbolised by the image of the phallos, which is not merely sexual but shows the life force and fertility over which he ruled. While Dionysos drinks and parties, artistic representations of him never show him partaking in sexual intercourse nor revealing his own genitals. Maybe this reflects the god’s identity as asexual: those who identify as asexual may have romantic feelings for others but not sexual attraction. The god’s avoidance of a rigid sexuality can be seen also as bisexuality. His appearance, which changes from that of a bearded man to that of a slim clean-cut youth around the fifth century bce, demonstrates sexual fluidity, in that he veers between masculinity and femininity, while never giving much away. Maybe it’s none of our business.

A warrior's gender identity

A warrior’s gender identity

[Warfare, 7]

Some images of warriors, like the one decorating this wine jug, don’t give much away regarding the identity of the person pictured. The renowned Greek warrior Kaineus (he/his), was once a beautiful maiden named Kainis (she/her). After Poseidon had raped Kainis, he offered her anything she wished in return for the assault. Kainis wished to be a man to be better equipped to defend themselves. They also wished to become impenetrable to the sword, which may reflect their desire to not be penetrated sexually. Kainis embarked on many heroic endeavours such as the Kalydonian boar hunt as well as voyaging with Jason and the Argonauts. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Caeneus (their Roman name) is described with virtus, a Roman term used for masculine characteristics of courage and heroism. For Kainis to have been once assigned female at birth, yet regarded so highly among warriors, was exceptional. For Kainis to be renowned as a warrior of great virtue makes them a transgender hero of. They are transgender in the sense that they transitioned from their gender assigned to them at birth. While such a term did not exist in Greek antiquity, there are other transgender characters from ancient texts. In Lucian’s Dialogue of the Courtesans 5, for example, Megilla/Megillos appears to present as a self-identified trans man.

Biromanticism

Biromanticism

[Death in Antiquity, 19]

The scene of two young male warriors with a woman that decorates this krater reflects romantic customs common among Greek warriors. In Homer’s Iliad, Achilles takes a female slave Briseis as a war-prize, a signal of status and power as well as sexual attraction. Is the woman in this triad such a prize? Homer tells also of the deep friendship between Achilles and his comrade Patroklos, which can be understood as homoromanticism, being romantically attracted to someone of the same gender as oneself. If Achilles was attracted to Patroklos and Briseis could we suggest it is a case of biromanticism? Affection between comrades is often dismissed as mere companionship between men, which denies the possibility of romantic motivations, yet there are other ancient stories of affection between male warriors. In his play Orestes, for example, Euripides tells us of such a connection between Orestes and Pylades. Tragedy and death looms over these men at every turn, so the only way to endure their hardships is by being together with their partners. Pylades told Orestes, “Your ruin would mean mine too, since friends share everything.” No remaining sources attest sexual relationships between Achilles and Patroclus or Orestes and Pylades, but to read the texts and deny the admiration reaching deeper than camaraderie says more of the audience than the myth itself. Homoromanticism was certainly omnipresent in the ancient Mediterranean and it was customary for men to have wives and families as well as male lovers.

Kohl pot

Kohl pot

[The body beautiful, 37]

It was common for both men and women in ancient Egypt to wear make-up, such as kohl—once held in this pot—around the eyes. This was especially prominent in the New Kingdom, where there was little emphasis on constructed gender roles, and both men and women wore the same make-up and jewellery and did equally laborious work indoors and outdoors. The fifth Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, Hatshepsut (she/her)—who reigned c. 1479 to 1458 BCE—used this to her advantage when she transitioned from Queen to the male role of Pharaoh, although there was little precedent for women holding high-status roles. She did not bow to expectations of her traditionally male authority. She rather enacted gender non-conformity in her reign and image. Hatshepsut asserted herself as armed with male weaponry and dress whilst reinventing the identity of the Pharaoh.