HIPPOS THE HORSE IN ANCIENT GREECE

Looking around the Ure Museum it is clear the horse was a popular subject for ancient Greek artists. Why are so many horses pictured in ancient Greek art?

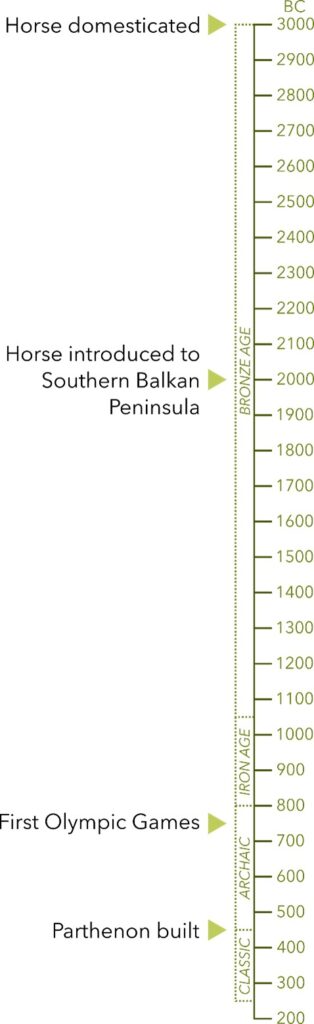

Horses were first introduced to Greece during the mid Bronze Age (circa 1800 BC), and by the Archaic (800–480 BC) and Classical (480–323 BC) Periods the animals were an important part of ancient Greek culture. Horses were expensive to buy and keep, so only the wealthy could afford them. Horses were a luxury, useful for leisure and signifying status [9]. The less wealthy became familiar with horses as spectators at public events [8, 15, 16], and horses featured in the religion and traditions shared by all classes: Poseidon, god of the sea, storms and earthquakes, was also god of horses, so the animals played a role in his worship [2, 3] and legendary heroes had named horses accompanying them in their adventures [5].

Horses were valued and admired by all ancient Greeks. Characterised as swift, loyal and noble animals, horses were therefore held in high regard above other domesticated and wild animals [11]. Artists were quick to recognise this respect for horses, which patrons wanted to exhibit [10].

The objects chosen for this exhibition, which all feature images of horses, explore the ancient Greek experience with the animals and the roles they had in religion, government, warfare and sport.