Representation: Disability and Art

Throughout history, artists have always sought to reflect the world around them. New styles, mediums and art movements have evolved assisting the process. Innovations, including paint tubes, allowed artists to increase their creativity.

These inventions were also fundamental in providing wider access to art. Some artists will have needed to adapt to accommodate disabilities. However, they may not have shared this at the time.

Not all disabled artists choose to show their disability, with some remaining hidden. These decisions are personal and are all valid.

In this exhibition, we will explore how disability is represented in our collection. Some of the artists included had a disability, while other pieces were chosen to represent and reflect other conditions.

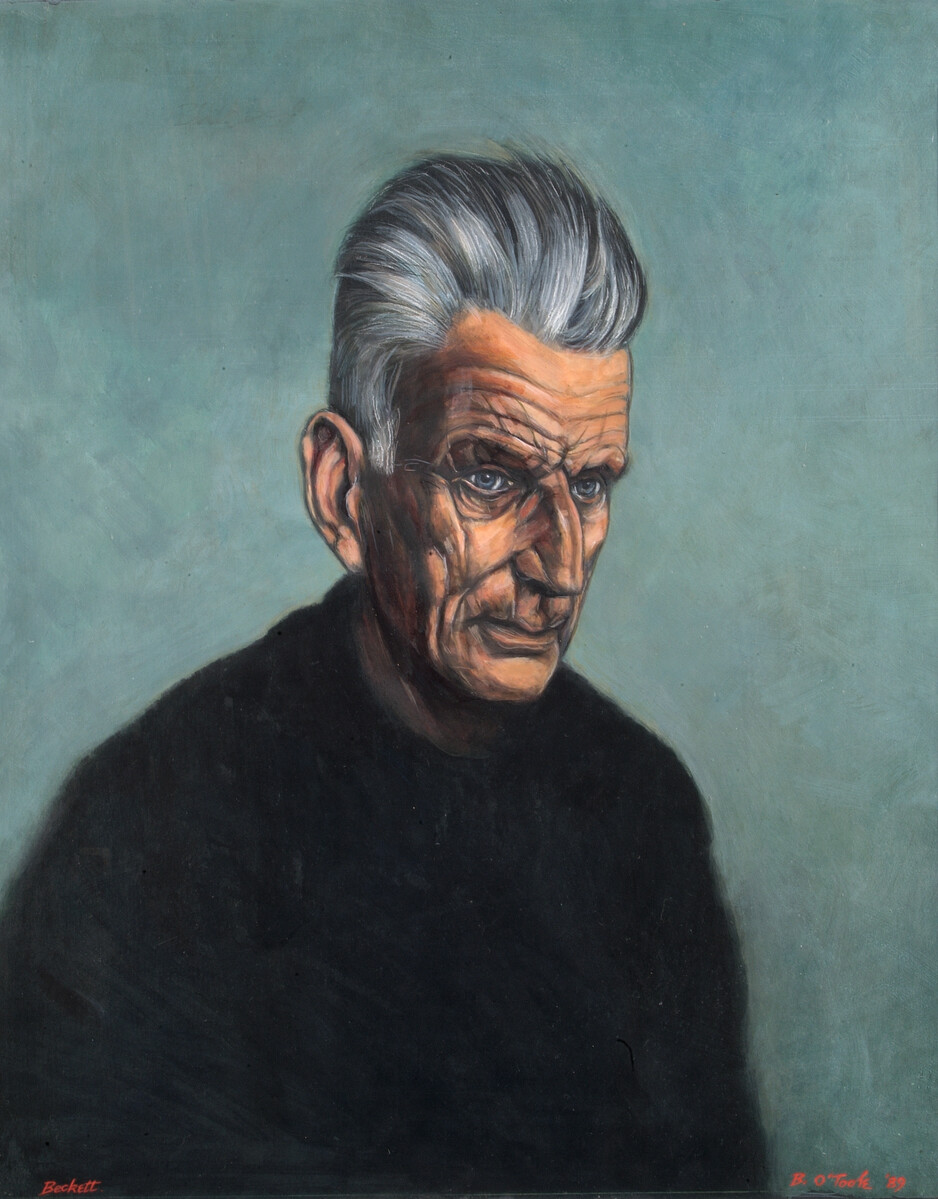

Samuel Beckett

Irish-born playwright, poet and novelist Samuel Beckett was considered a literary legend of the 20th century. Best known for his plays, Beckett received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969.

Whilst Beckett was not disabled, his writings can be seen as a platform for physical disability. Arguably his most famous work, Waiting for Godot, includes characters with both visible visual and verbal disabilities.

Credit: Samuel Beckett, B O’Toole, pain chalk and pastel on paper, 1989. UAC/10284.

John Bratby

John Bratby was diagnosed with extreme myopia, also known as nearsightedness, as a child. It was this condition which directly enabled him to study art. After being discharged from the army due to his myopia, Bratby received an ex-service grant, which he used to study at Kingston School of Art.

Associated with the Kitchen Sink School, Bratby painted in vibrant colours. This is a common trait found in artists with myopia.

Credit: Brian Aldiss, John Bratby, oil on canvas, 1978-1982. UAC/10260.

Albert de Belleroche

For those with Dyslexia and other Special Learning Difficulties (SPLD), this image resonates. Although it may have been unintentional by the artist, Albert Belleroche’s delicate hand evokes a familiar sense of patience and caring for many of those with hidden learning difficulties.

Credit: Etude de femme, Albert de Belleroche, black ink and wash on paper, 1864 – 1944. UAC/10568

Albert Egerton Cooper

Not all people are born with disabilities, Alfred Egerton Cooper lost most of his sight in his right eye due to chlorine gas in the First World War. However, he could still draw and differentiate colour. Appointed official artist of the Royal Air Force by 1917, Egerton Cooper returned to creating and teaching art after the war ended.

Best known for his portraits, this artwork is one of many pieces Egerton Cooper created after the damage to his eye.

Credit: Francis Evelyn Countess of Warwick, Alfred Egerton Cooper, oil on canvas, 1951 – 1955. UAC/10255

Stephen Dwoskin

Disability was a central theme in avant-garde filmmaker Stephen Dwoskin’s work. After contracting polio aged 9, Dwoskin used crutches and a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Rejecting the term “disabled” when it was applied to himself, Dwoskin often highlighted characters with disabilities in his films.

Dwoskin was also an artist, with a focus on abstraction. This piece reflects a close intimate moment that is often expressed in his work.

Credit: Two figures embracing, Stephen Dwoskin, oil on canvas. UAC/11063

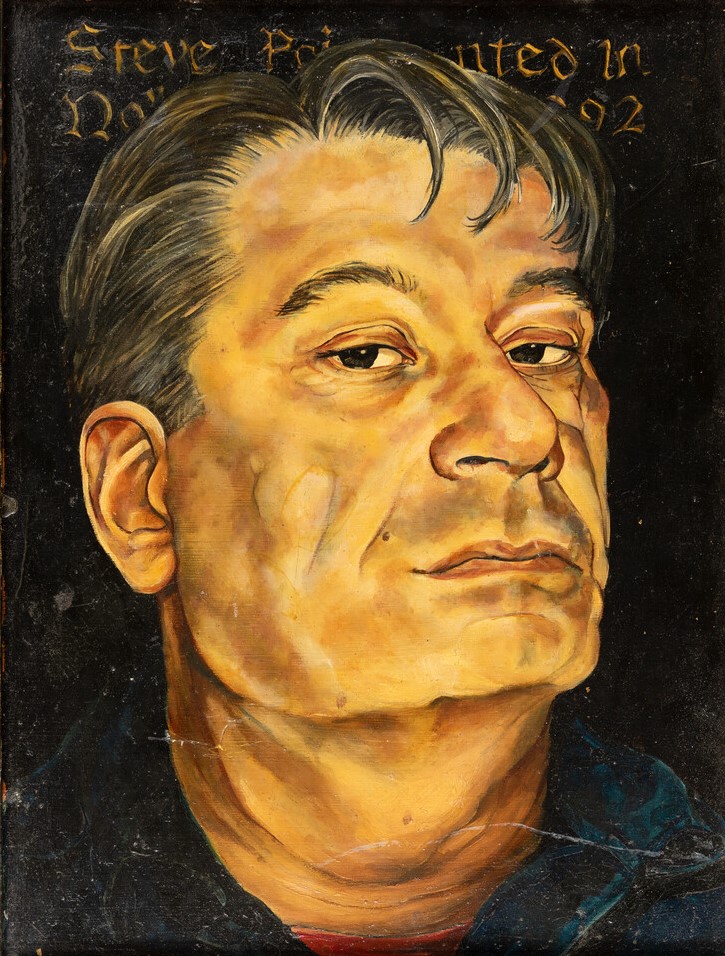

Dwoskin by Frances Turner

This portrait of Dwoskin was made by his ‘dear friend’, and girlfriend, Frances Turner. Obsessed with the human body in her work, Turner seems to have positioned Dwoskin to emphasise his strength.

Focusing her portrait on his head and shoulders with a raised chin, Turner has deliberately included no evidence of the disability he never sought to hide.

Credit: Portrait of Steve, Frances Turner, paint on board, 1990-1999. UAC/11034

Venus de Milo by Minnie J. Hardman

Immediately recognizable in art history, Venus de Milo is an icon of beauty which has stood the test of time. When she was originally created in Ancient Greece she had both arms. However, these were mostly missing when she was rediscovered in 1820.

Less than 80 years later, Hardman drew Venus de Milo without emphasising these missing limbs. Indeed, many Greek sculptures of the period were also amputees.

Credit: Study of the Venus de Milo, Minnie Jane Hardman, 1883-1889. UAC/10634

Dionysos by Minnie J. Hardman

Unable to draw semi-draped male figures from life, Minnie Jane Hardman learnt her trade by drawing ‘undraped antique statues’. Hardman’s detailed sketches reflect the skill required to create these sculptures.

The Study of Dionysos from east pediment of Parthenon, emphasises its shape, position, form and the points where the limbs end. These missing limbs appear as an afterthought, if it is one at all.

Credit: Study of Dionysos from east pediment of Parthenon, Minnie Jane Hardman, drawing, 1883. UAC/10617

Augustus John

Whilst diving into the sea in 1897, Augustus John suffered a serious head injury which lead to a change in his character. Several critics posited that the injury and subsequent recovery lead to an acceleration of John’s artistic growth.

We can find no evidence that John was diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury (TBI). However, there are studies which indicate that some individuals who have suffered TBIs have exhibited newfound abilities in art and other fields.

Credit: Welsh Landscape, Augustus Edwin John, oil on board, 01/01/1900 – 31/12/1924. UAC/10544

Sir Alfred Munnings

Sir Alfred Munnings lost sight in one eye after an accident in 1898, when lifting his dog over a briar hedge. In 1899, a year after the accident, Munnings’ work was exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition.

In World War I Munnings enlisted and became an army horse trainer in Reading and an official war artist. In 1944 received his knighthood and was elected president of the Royal Academy. With injuries to the eyes, depth perception can become an issue and the brain can start adapting to compensate for the sudden reduction in vision.

Credit: Richard Lloyd Pearson, Sir Alfred James Munnings, oil on canvas, 1918 – 1922. UAC/10038

Louis Vidal

French sculptor Louis Vidal moved from studying anatomy to sculpture after becoming blind. With help from assistant Alfred Barye, Vidal learned how to work marble, bronze and plaster, signing most of his work Vidal Aveugle, ‘Vidal the Blind’.

This self-ascribed title suggests a level of pride and peace from Vidal. Vidal often sculpted animals in bronze, and these pieces are highly prized.

Credit: Standing lion, Louis Vidal, sculpture, 1876. UAC/10047

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler was controversial during his lifetime for both his art and personal views.

An advocate of slavery, Whistler initiated (and lost) a racially motivated fight with a black passenger on the steamer Shannon in 1866. This failed assault resulted in Whistler describing his hand as being ‘utterly maimed and disabled’.

While this may have impacted his work, there is no further information as to how badly he was injured. Was he exaggerating his injuries for the sake of discrediting the man he attacked?

We want to make clear that these views are not ones that are accepted today nor one that we condone or support, nor do we support enacting violence for any reason.

Credit: The Fellow Traveller (Study of Ronald Murray Phillip), James Abbott McNeill Whistler, 1900-1901. UAC/10519