Preserving the Picturesque

These watercolours were painted by John Paget (1811-98). Paget was a magistrate who spent his spare time writing and painting. His granddaughter gave these paintings to the Council for the Preservation of Rural England in 1948. This is the first time they have been displayed in over 70 years.

Watercolour is one of the most accessible types of painting. It is widely used by professional and amateur artists because it is affordable, portable, and easy to clean up. Watercolour became popular in Britain from the mid-1700s. Artists turned to the natural world for inspiration, and they used watercolours to record a rapidly changing world. They travelled across England, Europe, and the British Empire, experimenting with new colours and techniques.

Paget’s artworks show ideal, peaceful landscapes, as well as evidence of a countryside under threat. Ruined abbeys, castles and buildings appear as part of nature. By the mid-twentieth century, Paget’s watercolours were admired for celebrating a recognisably British style.

Millom Castle, Cumbria, 14 August 1879

Located on the south-west edge of the Lake District, Millom Castle looks out toward the Irish sea. Once part of a chain of coastal fortifications, it was designed to repel Scottish raiders. The castle was badly damaged during the English Civil War and gradually fell into ruin.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the Lake District became a popular tourist destination. When the Windermere railway opened in 1847, it became easier for artists and writers to visit. The castle ruins became a favourite subject.

Here, Paget directs our gaze toward the castle’s main staircase. The ivy growing through the weathered stonework reveals nature’s slow reclamation of the man-made structure.

West Banqueting House, Gloucestershire, 15 September 1881

This extraordinary building — designed to host banquets — is all that survives of one of the most important Jacobean sites in England. The rest was destroyed by fire during the English Civil War.

In the nineteenth century, artists and architects revived the Jacobean style. This was partly a reaction against the mass-produced goods of the Industrial Revolution. They celebrated and drew inspiration from its distinctive, dramatic and intricate craftsmanship.

Here, Paget demonstrates his technical ability by drawing attention to the architectural details of the West Banqueting House. On the right, the sparsely leafed tree heightens the sense of drama within the composition.

Bothal Castle, Northumberland, 1874

Northumberland’s dramatic scenery — moors, coastlines and castles — aligned perfectly with Paget’s taste for picturesque and Romantic views. Here, he portrays Bothal Castle, perched strikingly above the River Wansbeck. The muted colours suggest an overcast day and remind us of the challenges of painting outdoors.

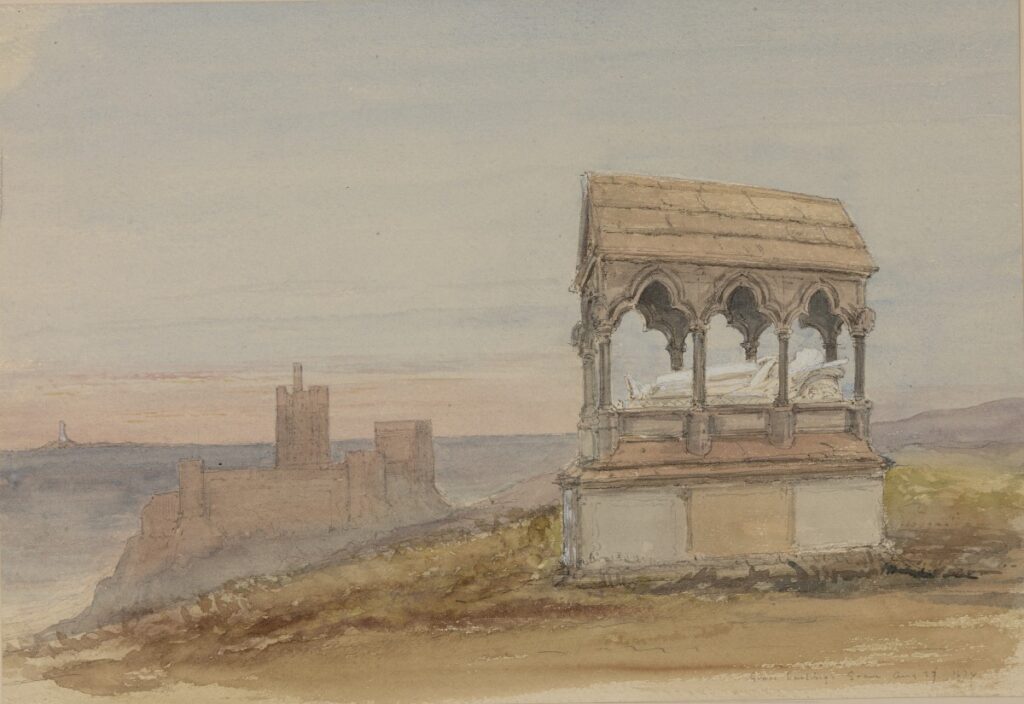

Grace Darling’s Grave, Northumberland, 27 August 1874

The Gothic memorial to Grace Darling stands fifty miles north of Bothal Castle. Darling, who lived in the lighthouse seen on the left, rose to national fame in 1838 after helping her father rescue nine sailors from a shipwreck. Her courage captured the Victorian imagination and she was celebrated in newspapers, paintings and popular songs.

Knaresborough Castle, Yorkshire, 21 August 1874

Towering above the River Nidd, Knaresborough Castle was one of the most important royal strongholds in northern England. By the nineteenth century, the castle was already a picturesque ruin.

In the background, Paget includes the historic Royal Forest of Knaresborough, now Knaresborough Forest Park. Had he chosen the opposite vantage point, the scene would have featured the Knaresborough viaduct—one of Yorkshire’s most iconic Victorian landmarks. Before its construction, Knaresborough remained a relatively isolated town. Afterward, the town became part of the booming Victorian leisure circuit.

Furness Abbey, Cumbria, 30 July 1879

A blue sky is seen through the ruins of Furness Abbey in the Lake District. Like many of the sites that Paget sketched, Furness Abbey was an essential destination for artists on their picturesque tour.

William Wordsworth, in his celebrated autobiographical poem, The Prelude (1798-99) captures the gentle decay of the Abbey. He writes:

Here, where, of havoc tired and rash undoing,

Man left this Structure to become Time’s prey

A Soothing spirit follows in the way

That Nature takes, her counter-work pursuing.

See how her Ivy clasps the sacred Ruin

Fall to prevent of beautify decay;

And, on the mouldered walls, how bright, how gay,

The flowers in pearly dews their bloom renewing!

Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, Warwickshire, 26 August 1874

By the nineteenth century, Shakespeare had become a national icon. The family home of his wife, Anne Hathaway, was woven into his mythology.

Paget was one of many tourists who travelled to Stratford-upon-Avon seeking out places associated with Shakespeare’s life. When he visited in 1874, he would have met Mary Baker, a descendant of Hathway who ran popular tours of the cottage. In 1892, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust raised £3,000 to purchase the cottage from Mary. Soon after, it opened its doors to the public, charging a one shilling entrance fee. To align the appearance of the cottage with the romantic narrative associated with it, the Trust cleaned and repaired it, and re-thatched the roof. Mary continued to give tours until her death in 1899.

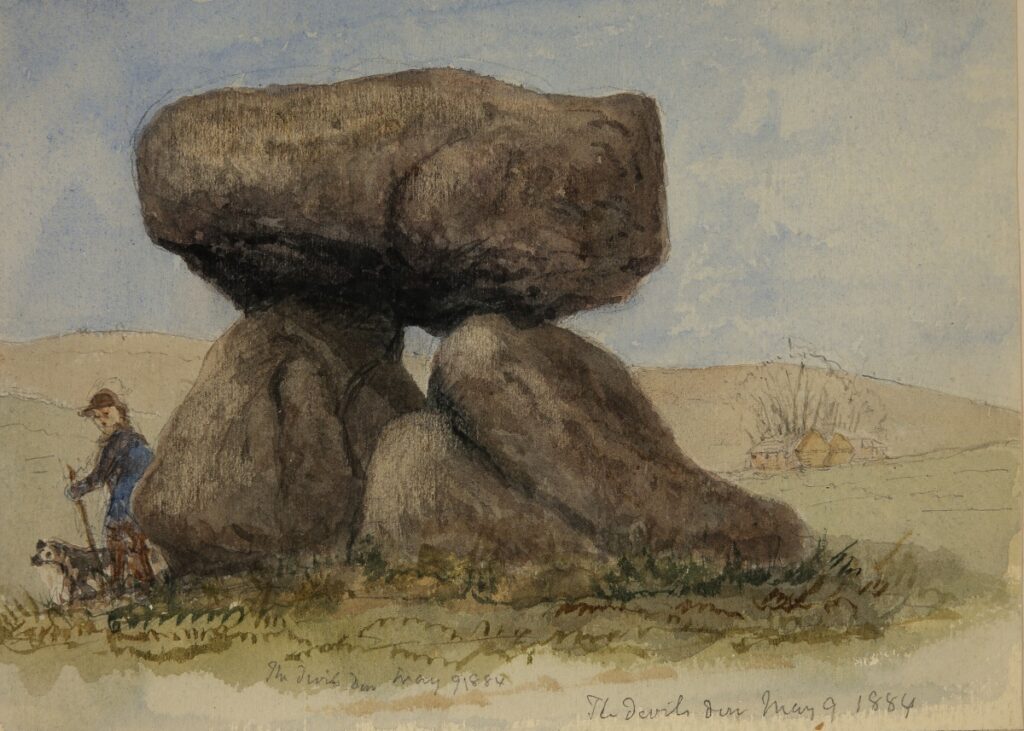

Devil’s Den, Wiltshire, 9 May 1874

To reach the Devil’s Den on the North Wessex Downs today, you need to hike through several fields, much as tourists did in the nineteenth century. The Neolithic dolmen (a type of burial chamber) was built around 4000-3500 BCE and the surviving stones are just the entrance to what was a substantial tomb.

Artists like Paget were intrigued by the mystery surrounding this site, which appeared in several nineteenth century travel guides.

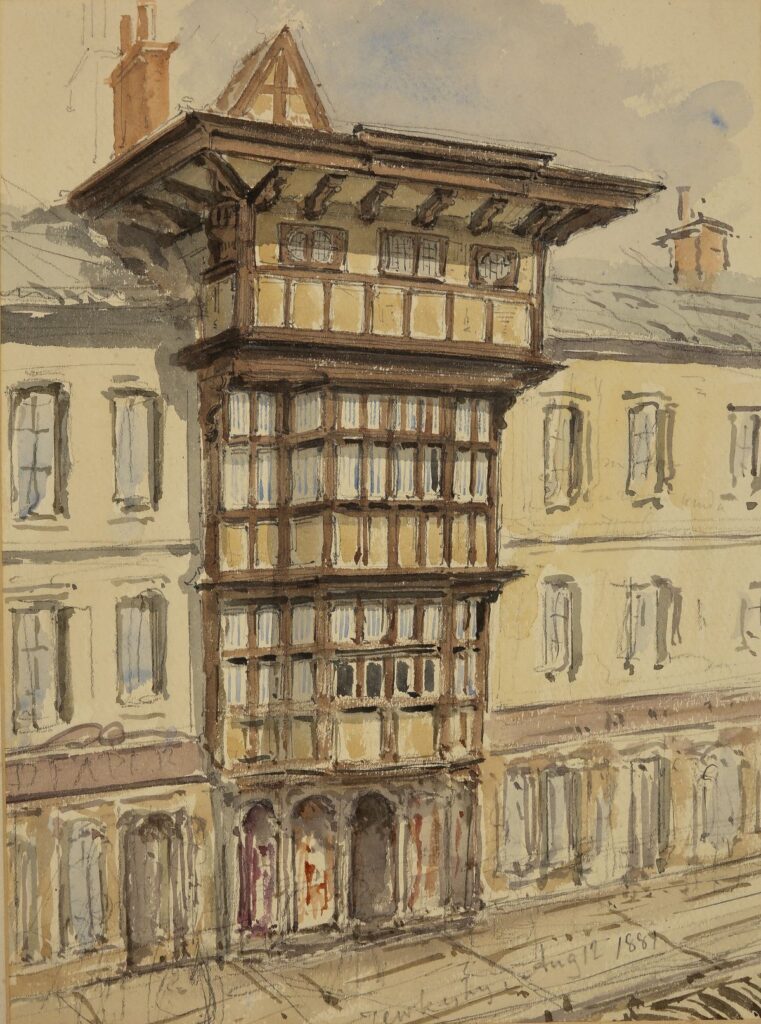

Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, 12 August 1881

Although most of Paget’s sketches are landscapes, he also visited towns that preserved their historic character. He was attracted to Tewkesbury because of its famous ‘black and white’ medieval and Tudor architecture.

Ilfracombe, Devon, 17 July 1884

During the nineteenth century, Ilfracombe transformed from a modest fishing port to one of Britain’s most popular Victorian seaside resorts. In the summer, steamships from Bristol, Swansea and south Wales brought thousands of tourists to the picturesque town. Ilfracombe’s scenery — steep cliffs, rock pools, tidal beaches and wild headlands — embodied the Romantic coastal ideal, making it a popular destination for artists.

Here, Paget depicts the harbour side of Ilfracombe, looking toward Lantern Hill. Perched on the hill is the fourteenth century St Nicholas’s Chapel, England’s oldest working lighthouse. By adopting this perspective, Paget is able to showcase the expanding town, the spiritual and maritime landmark, and the dramatic coastline.

Lustleigh, Dartmoor, Devon, 14 October 1886

Lustleigh, a small rural community in the Wray Valley, was shaped by the rapid changes taking place across Dartmoor. By the time Paget visited in 1886, the railway had improved access to the area, attracting visitors drawn to Dartmoor’s rugged, picturesque beauty.

Paget depicts a set of rural buildings, anchoring the composition with the sixteenth-century Church House on the left. Just out of view stood the Cleave Hotel — formerly Gatehouse Farm — which had recently been converted to accommodate tourists. Only three years earlier, the Dartmoor Preservation Association had been established to address the new pressures that were placed on the moor.

Paper Conservation: Caring for Watercolours

The pigments in historic watercolours are susceptible to irreversible light damage.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, watercolours were usually stored in albums or portfolios and viewed privately. But as watercolour artists gained status and recognition, their works began to be shown in public exhibitions. This shift meant many artworks, including those in this exhibition, were damaged by light and lost some of their original brilliance.

For this display, our Paper Conservator carefully remounted the works and placed them in new frames with UV-protective glass. The works are shown in low light to help preserve them for the future.