Thomas Graham Briggs: Collecting the Caribbean

By Amara Thornton

Thomas Graham Briggs was one of the most noted collectors of Caribbean antiquities in 19th century Barbados. Numerous artefacts from his collection are now housed at the British Museum, and other museums in the UK and beyond. This post will offer a profile of Briggs as a gateway, so to speak, to highlighting the wider context of artefacts from the Caribbean long held in British museums.

I began to examine the collection histories of these artefacts as part of “Narrating the Diverse Past“, a project funded through a collaborative partnership between the British Museum and the University of Reading. As a historian of archaeology I am interested in how collections histories reflect the deep and entangled colonial relationship between Britain and the Caribbean. The significance of this relationship is increasingly visible today with the findings of the Legacies of British Slave ownership and Colonial Countryside projects, debates about decolonisation, restitution, representation and the legacy of empire. And having both African-Caribbean-British ancestry myself, this history is my history too.

Briggs’s family had long prospered from the sugar-trade, a prosperity gained initially through the labour of the enslaved people who worked the family’s estates on the island. The first English Briggs settled in Barbados in the 17th century and became a captain in the Barbados Militia. Jim Webster’s sugar-works database indicates that by the mid-19th century, the family’s holdings included sugar-works Maynard’s, Six Men’s, and Welch Town in St Peter’s Parish, and other sugar-works in St Lucy and Christ Church parishes. According to the Legacies of British Slave Ownership database, Thomas Graham Briggs’ father Joseph Lyder Briggs was awarded thousands of pounds in compensation for loss of income from enslaved people becoming free by 1838.

Graham Briggs, as he was known, was born in 1833 – the year the Act for the Abolition of Slavery was passed. Joseph Briggs acquired Grenade Hall (renamed Farley Hill), the estate that is now most associated with his son Graham Briggs, soon afterwards. The Briggs family wealth made it possible for Graham Briggs to attend Codrington College, the most elite educational institution in Barbados.* He completed his studies there in the early 1850s, then made the long journey to Britain and Trinity College Cambridge, where he obtained both BA (1856) and MA (1862) degrees. While Briggs maintained close ties with Britain throughout his life, he considered himself a “West Indian”, and a champion of West Indian interests, particularly relating to the “resident proprietor” class of which he was most definitely a part.

Between his two degrees at Cambridge, he married fellow Barbadian Mary Jane Howell, who was like him from the island’s elite planter class.** The couple bought further properties in Nevis, eventually totalling three – Stony Grove, Old Manor and Round Hill. They travelled extensively – within the Caribbean, in the United States and in Europe – and made regular trips to Britain. Alongside holding political positions on the Executive Councils of both Barbados and Nevis, Graham Briggs was known as an agriculturalist. In 1870 was elected a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society, and the archive of Kew Gardens includes his substantial correspondence with the then Director, Joseph Hooker. He was given a baronetcy in 1871 and allocated a coat of arms.

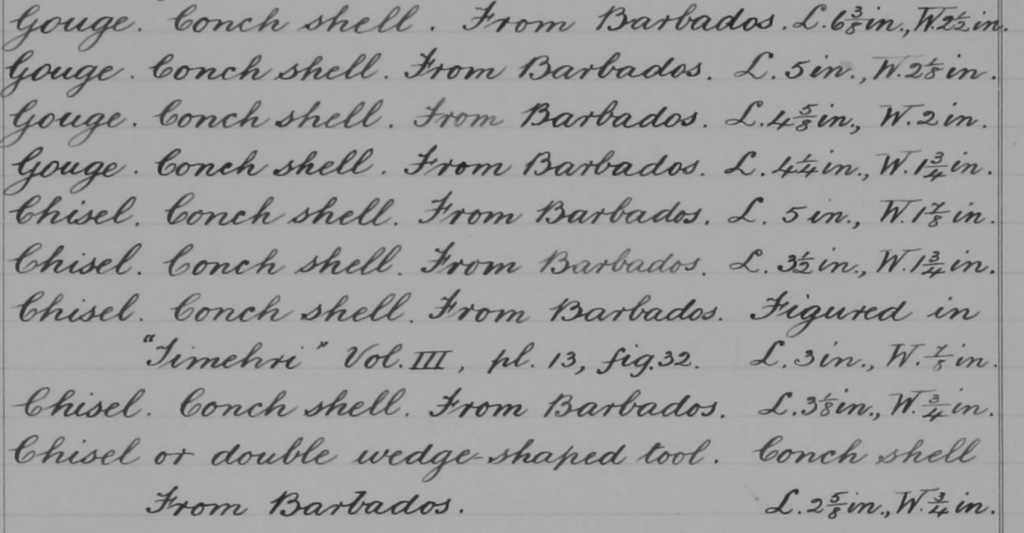

It is unclear at present when Graham Briggs began collecting ancient artefacts, but by the end of his life he had cabinets full of them in his Farley Hill mansion. The British-American writer James Henry Stark, author of a detailed guide to Barbados, noted that Briggs purchased many ancient shell implements from the (unfortunately unnamed) Black Barbadians who found them (Fig 1). Local collectors of antiquities known to Briggs in the Caribbean helped enrich his collection further. By the early 1880s the significance of his collection was known beyond Barbados. Everard im Thurn, the first editor of the British Guiana journal Timehri, published a lengthy illustrated analysis of the artefacts in Briggs’ possession in Timehri in 1884.

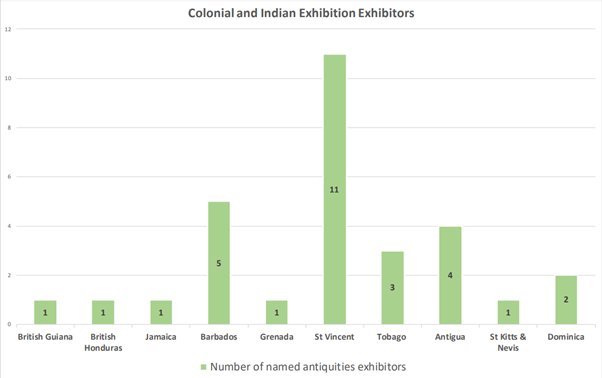

Two years later Briggs sent a sample of his collection to South Kensington for the first Colonial and Indian exhibition, one of a series of similar events that followed the Great Exhibition of 1851. This large-scale event, held between May and October 1886, saw residents of and those with links to Britain’s empire contribute all manner of items representing the materials – raw, handmade and manufactured – and cultures of their respective homelands, places of residence or travel. Some objects loaned had been forcibly taken by British imperial troops (including West India regiments who were made to perform non-combat roles) during action which destroyed the residence of King Kofi Karikari at Kumasi, Ghana during the Third Ashanti War. In what was then an established practice for such events as Sadiah Qureshi has shown, there were also “displayed peoples”, small groups of Indigenous men, women and children (re)creating their cultural practices in ‘representative’ surroundings for a paying audience. Among them were a group from British Guiana.

The West Indies section of the Colonial and Indian exhibition was in the East Gallery of the temporary buildings housing the displays, accessible from the Exhibition Road entrance (on ground that Imperial College London now occupies). Arched rooms, emblazoned at entrances with the names of each island, contained tables and shelves stuffed full of goods. There was a Picture Gallery where scenes of the landscapes, peoples, flora and fauna of the Caribbean, most produced by local residents (including over a hundred paintings by Edith, Lady Blake, another key collector of artefacts from the Caribbean), could be admired. A 35-member band, Black and Mixed-heritage Jamaican musicians of the 1st West India Regiment, played in the exhibition grounds twice a day during the summer.

It is unclear whether Briggs attended the Exhibition in person, but he was in Britain the following year, and in poor health. He died in London in October 1887. After his death, the parts of his collection remaining in Britain were in the hands of his widow and extended family. Letters in the British Museum’s archive indicate that at some stage they were on display in the Baker Street Bazaar (where, until 1882 Madame Tussaud’s Wax-Works had been exhibited) in a room rented by Mary Jane, Lady Briggs. The letters show that a selection of the collection was acquired by the Charles Hercules Read for the Christy Collection in 1889. The purchase was made through Briggs’ nephew Charles Kenrick Gibbons. Artefacts from Briggs’ collection now held in the British Museum include adzes, axes, hammers and pestles, as well as an unusual carved stone column from Nevis (see Am,.+4419). Gibbons also sold parts of Briggs’ collection other institutions, including the National Museum of Scotland (see above), and the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge (see, for example, E 1894.51).

Briggs’ story as a collector ends there at present. But there are further avenues of investigation to pursue. How much of his personal correspondence is extant in UK archives and collections? Did he discuss the artefacts he collected in his letters? Did he name some of the Black Barbadians he purchased artefacts from? How can their stories be effectively integrated into the history of these artefacts in museums and beyond? These are some of the questions I’ll be thinking about as I continue my research on histories of Caribbean collections. I hope there will be more to come.

Thomas Graham Briggs is a featured collector in Mapping Collections Histories: Barbados and Britain, a digital exhibition produced as part of the “Narrating the Diverse Past project.

Further Reading/References

Adderley, Augustus. and Eves, C. Washington. 1886. Jamaica at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition. London: Spottiswoode & Co.

Bennett, Melissa, 2018. ‘Exhibits with real colour and interest’: representations of the West India Regiment at Atlantic World’s Fairs. Slavery and Abolition 39 (3): 558-578.

Briggs, Samuel, 1889. The Archives of the Briggs Family. T. Shenck.

Clarke, C. Howell, 1956. Farley Hill, St. Peter and Sir Graham Briggs, Bart., Its Owner. The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society 23 (2): 103-111.

Colonial and Indian Exhibition, 1886. Handbook and Catalogue: West Indies and British Honduras. London: W. Clowes & Son.

Cundall, Frank (Ed.) 1886. Reminiscences of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition. London: William Clowes & Sons, Ltd.

Fraser, Henry and Hughes, Ronnie, 1986. Historic Houses of Barbados. Bridgetown: Barbados National Trust.

im Thurn, Everard, 1884. Notes on West Indian Stone Implements. Timehri 3: 103-137.

Legacies of British Slave-ownership database. ‘Joseph Lyder Briggs’, http://wwwdepts-live.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2660 [accessed 23rd November 2020].

Legacies of British Slave-ownership database. ‘Benjamin Carleton Howell’ http://wwwdepts-live.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/41022 [accessed 23rd November 2020].

Mair, Robert H. (Ed). 1884. Debrett’s Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage, and Companionage. London: Dean & Son.

Qureshi, Sadiah. 2011. Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Royal Commission, 1886. Official Catalogue of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition (2nd edn.) London: William Clowes & Sons, Ltd.

Salmon, Charles Spencer, 1888. The Caribbean Confederation. London: Cassell & Co.

Stark, James H. 1893. Stark’s History and Guide to Barbados and the Caribbee Islands. Boston: Photo-Electrotype Co., Publishers.

Thornton, Amara, 2020. Colonial Archaeology in the Caribbean. Reading Room Notes. [Blog]

Webster, Jim, 2020. Barbados Sugar-Works. BajanThings. [Online].

* Codrington College was founded by Christopher Codrington, the same Barbados plantation owner who left £10,000 to All Souls College, Oxford for a new library. Codrington’s name is now to be dropped from the All Souls Library for his association with slavery. Codrington College was built on the Codrington plantation lands, which continued to be worked as sugar plantations throughout the 18th century and after emancipation.

** Her father, Benjamin Carleton Howell, had also received several hundred pounds of compensation for the enslaved people freed on his estates in Barbados.