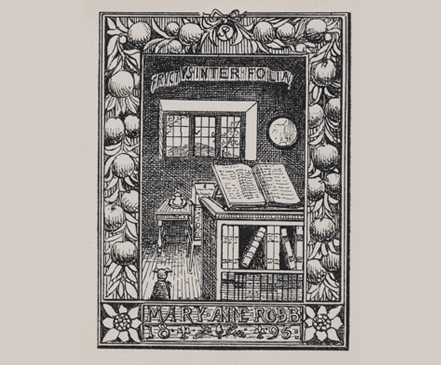

Bookplate stories: Mary Anne Robb 1895

This post is part of a series of stories written by Liz West, Fellow in Ephemera Studies, about the Amoret Tanner bookplate collection. Read more here

·

Story one

Mrs Robb’s Bonnet

♣

Mary Anne (or Ann) Robb (1829-1912) was a botanist, horticulturalist, artist and plant collector. Her botanical drawings are held in the library of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew but her most famous legacy is a plant called Euphorbia amygdaloides robbiae.

Mary Anne developed her love of plants whilst growing up on the Great Tew estate in Oxfordshire. As an adult, she was friends with a number of eminent gardeners and horticulturalists, including Gertrude Jekyll, Edwin Lutyens and E A Bowles. After the death of her husband, Mary Anne travelled across Asia on plant-collecting expeditions. It sounds like she travelled in some style: amongst her luggage was a flamboyant hat, transported in its own box. On a trip to Turkey, having collected many plants, she came across the euphorbia, growing wild by the side of a road. She had run out of containers and so her solution was to deploy her hat box, and the plant was transported back to England, tucked under her bonnet. Another version of the story has it that the plant was secreted in the hat box in order to smuggle it through customs. Either way, this unusual mode of transport lent the plant its common name: Mrs Robb’s Bonnet. It remains a popular fixture in many gardens, and is the holder of the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit.

·

Story two

Bookplates and wordplay

♣♣

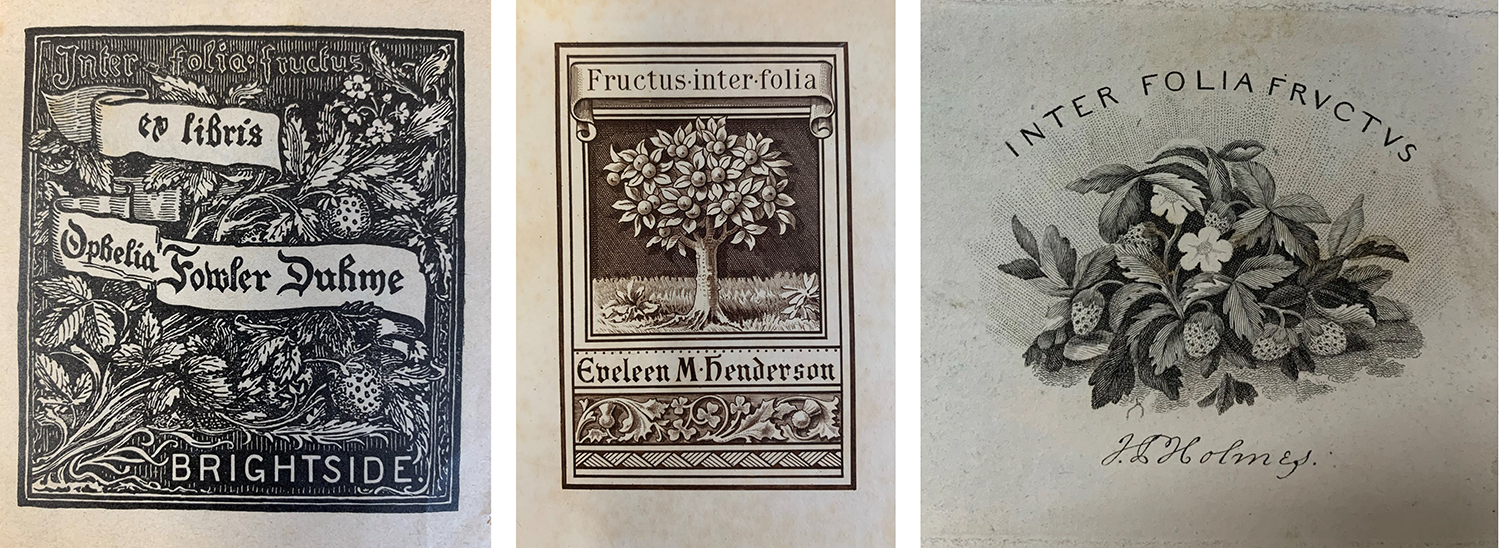

You’ll notice that Mary Anne’s bookplate features a Latin quotation ‘Fructus Inter Folia’, translated as ‘fruits among the leaves’. The bookplate’s illustration depicts a border of leaves and a fruit that looks like apples, framing a central picture of a bookshelf and an open book. Folia, of course, applies to the leaves of both a plant and a book, and fructus refers to the joy of reading and learning – the way that knowledge bears fruit in so many ways. The quotation is also often found as ‘inter folia fructus’. It was a popular choice, and features on a number of bookplates found in the collection at the Centre for Ephemera Studies. Here are just a few other examples:

Fructus inter folia

Wordplay is a common feature of bookplates, particularly those dating from the mid to late nineteenth-century onwards. It offers an opportunity for the bookplate owner to share a little of their character and interests, and to place the stamp of their own personalities within the images selected. The result is akin to a private joke, shared between friends.

On the right, Violet Howard’s plate features a bouquet of violets. Fittingly, a copy of this plate has been found in an edition of Robert Sweet’s Cistineae. The Natural order of Cistus, or Rock-Rose; illustrated by coloured figures & descriptions of all the distinct species, and the most prominent varieties, that could be at present procured in the Gardens of Great Britain. Sweet was a famous horticulturist, nurseryman and author.

Another, more playful example, is the bookplate belonging to Margaret April (centre above). A bunch of flowers in an April shower?

Finally, on the left, is a vase of lilies, engraved by Charles William Sherborn in 1890 for the bookplate of Lily Antrobus’s bookplate.

·

Story three

The plant hunters

♣♣♣

Mary Anne Robb was not alone in her plant collecting activities. During the eighteenth and nineteenth century, botanists and plant hunters were despatched across the globe by garden and nursery owners keen to acquire new species to establish in their gardens. Plants that are a familiar part of our horticultural landscape, such as rhodendrons, magnolias and camellias were brought to the UK from China, and thrived in the British climate. Growing new and exotic varieties became a status symbol for wealthy Victorian landowners, and the plant hunters fed the demand. Many National Trust properties have gardens stocked with specimens first sourced centuries ago from all over the world.

The most famous plant hunters of the period, including Ernest Wilson, Reginald Farrer, George Forrest, brought back thousands of plants from their travels, but another plant hunter had a different mission. Marianne North (1830-1890) travelled just as far afield as her male contemporaries – including visits to Canada, Australia, Singapore, Borneo, Japan and the Seychelles – but rather than bringing back the plants she hunted, she captured their smallest details in intricate oil paintings. Her approach was a departure for botanical art of the period, which traditionally used watercolours on a plain background. Marianne painted her studies in situ, with vivid colours and detailed backgrounds, and the information she shared about the habitats in which she found the plants she depicted was invaluable to botanists. Many of her paintings are still on display at the Marianne North Gallery at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

·

Story four

Other bookplates belonging to women botanists and gardeners

♣♣♣♣

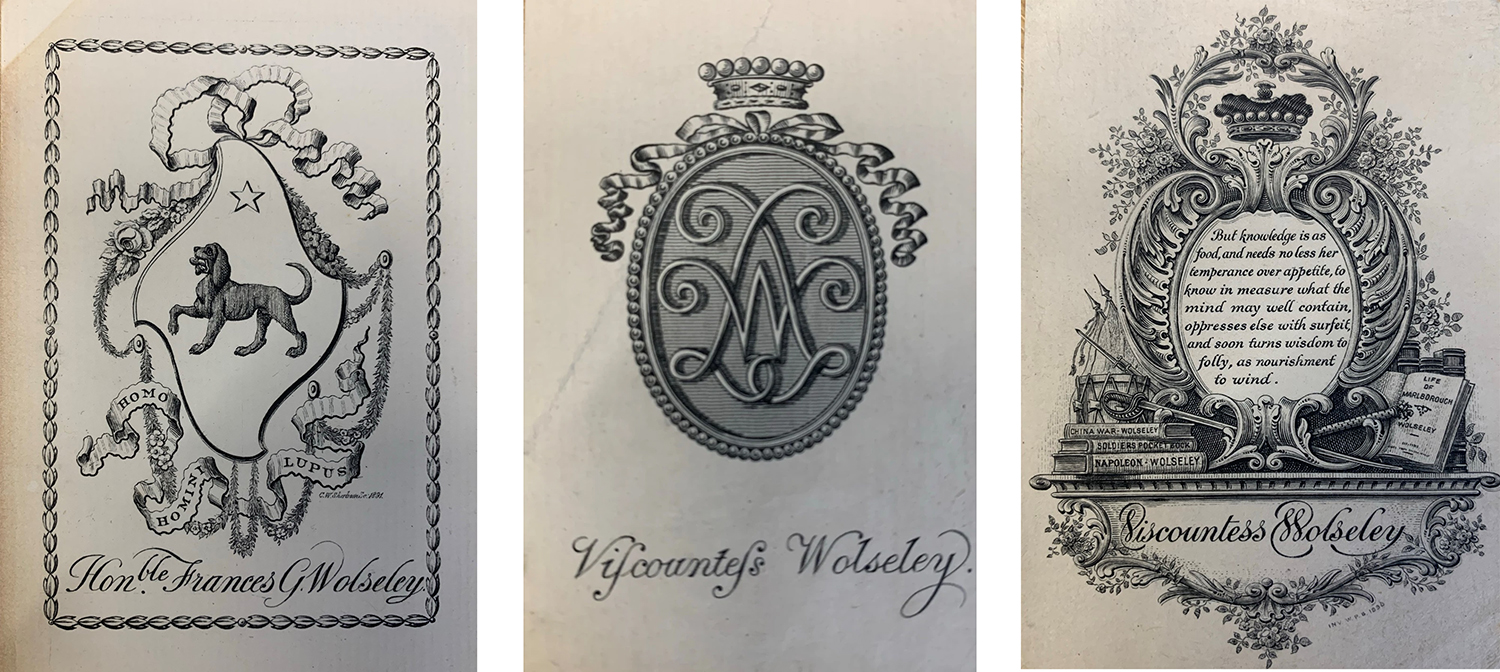

Violet Howard wasn’t the only fan of Robert Sweet’s books. Mary Anne Robb’s bookplate is found in a copy of Sweet’s Hortus Britannicus: or, A Catalogue of Plants, Indigenous, or Cultivated in the Gardens of Great Britain, published in 1830. Indeed, for Georgian and Victorian women, botany was the most accessible scientific field in which to exercise their interest. Our bookplate collection contains a number of examples of bookplates owned and designed by women botanists, horticulturalists and gardeners. Frances Garnet Wolseley, 2nd Viscountess Wolseley (1872-1936) was an English gardening author and founder of the Glynde College for Lady Gardeners, in East Sussex. She campaigned for women’s professional involvement in horticulture and wrote several books in support of this, the best known of which was Women and the Land (1916). She designed several bookplates for herself and for friends and family, as well as commissioning work from designers including Charles Sherborn, the creator of Lily Antrobus’ bookplate pictured above. We have some examples in the collection:

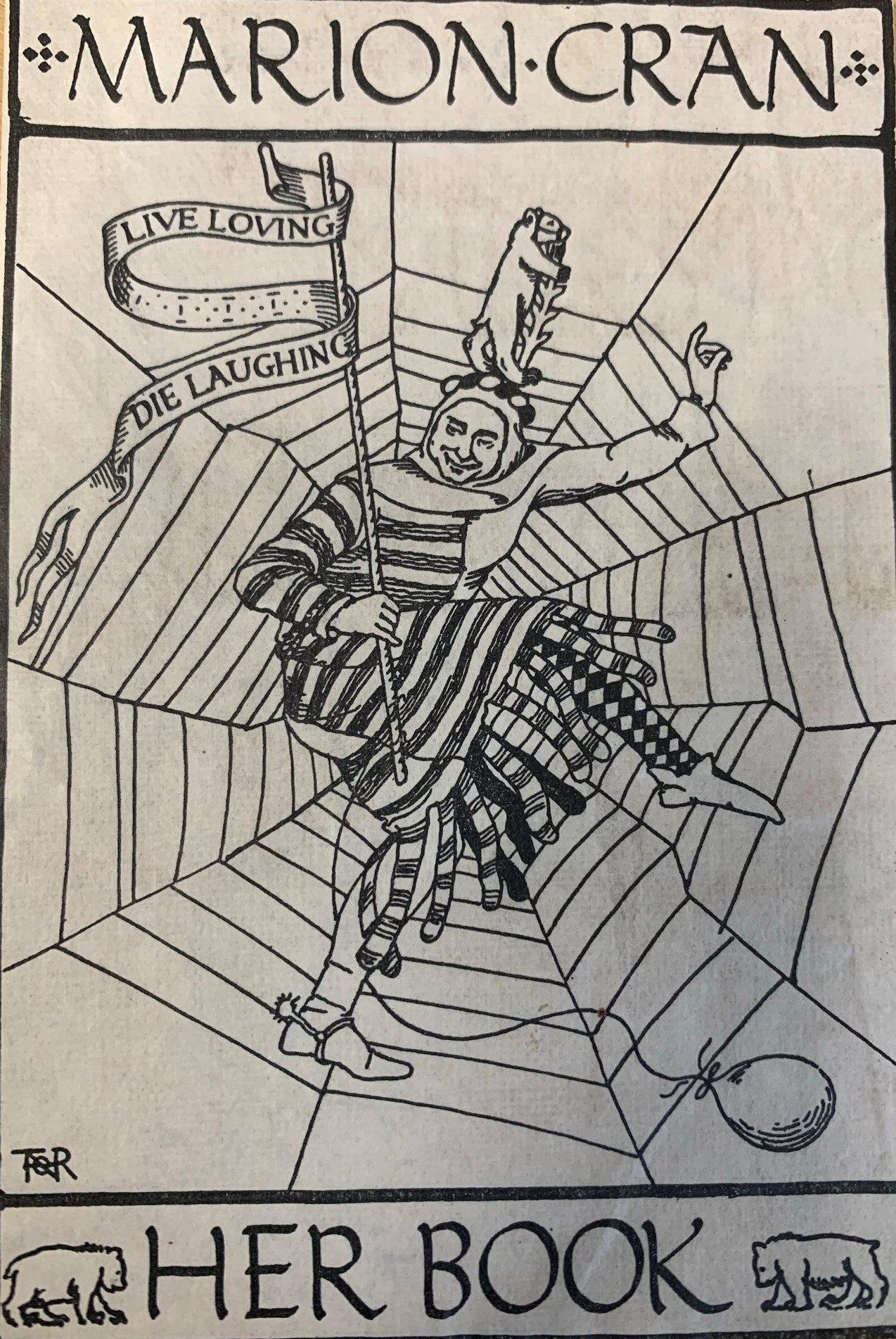

Another pioneering woman in the field (literally!) was Marion Cran (1875 – 1942) garden writer and Britain’s first female gardening broadcaster. After appearing on Women’s Hour in the early Twenties, she presented a fortnightly programme, Gardening Chat, from 1923 onwards. Due to the work of campaigners such as Frances Wolseley, horticulture was becoming increasingly possible as a career for women, and Marion tapped into this interest, becoming one of the BBC’s first celebrities.

Another pioneering woman in the field (literally!) was Marion Cran (1875 – 1942) garden writer and Britain’s first female gardening broadcaster. After appearing on Women’s Hour in the early Twenties, she presented a fortnightly programme, Gardening Chat, from 1923 onwards. Due to the work of campaigners such as Frances Wolseley, horticulture was becoming increasingly possible as a career for women, and Marion tapped into this interest, becoming one of the BBC’s first celebrities.

Although she was a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society, what really appealed to Marion’s audience was her informal approach and descriptive, engaging style, typified by the title of her first book: The Garden of Ignorance: The Experiences of a Woman in a Garden. Her second book, The Garden of Experience cemented her reputation and she became a household name, contributing articles to magazines and newspapers, and making guest appearances at fetes and garden shows across the country. She continued to write books after her broadcasting career ended, switching to novels in later life, and she was also a well-respected breeder of Siamese cats. Her rather eccentric bookplate, pictured here, gives a flavour of a woman who, in the words of Leonard Grimble, was ‘a genial companion whose mood is infectious’.

·

Further reading

Marion Cran’s The Garden of Ignorance: The Experiences of a Woman in a Garden was reissued in 2017 by Cambridge University Press

Marianne North: The Kew Collection, Kew Publishing, 2018. Over 800 colour botanical paintings

Fictional accounts of Victorian women botanists:

The Signature of All Things, Elizabeth Gilbert, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013

Unsheltered, Barbara Kingsolver, Faber & Faber, 2018