Nav

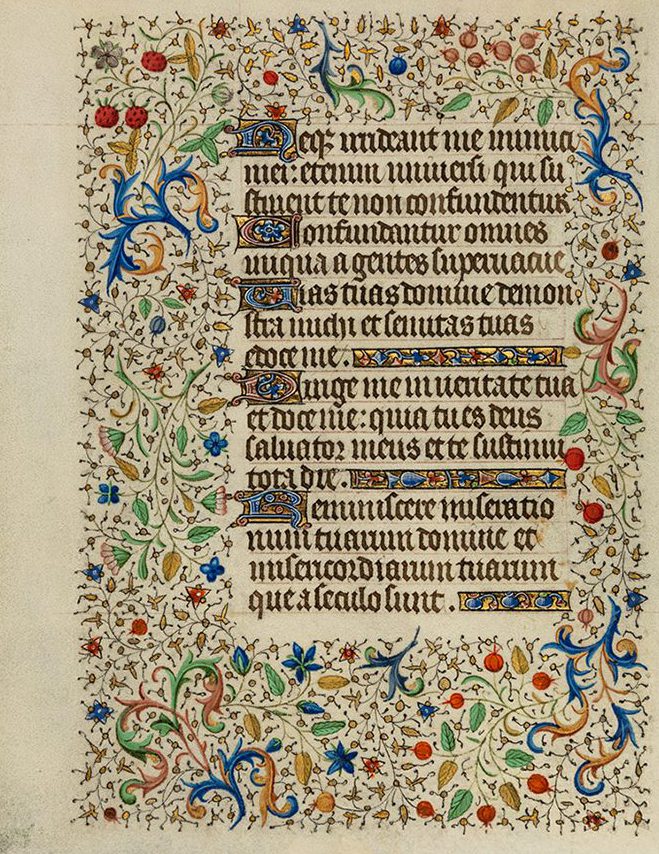

Leaf from a Book of Hours (c.1450)

[Script: Textualis Formata (Textus Quadratus)]

Written in Latin, produced in Paris, France

A book of hours is a type of prayer book devised for lay members of the Church. They were compilations of a number of different devotional texts, which the owner could read at home or carry about on special occasions. Due to their simplified structure and small size, they are often considered the ‘best-seller’ of the medieval world.

This leaf is from a French book of hours, and contains parts of Psalms 22 and 34. The beautifully decorated border depicts acanthus and oak leaves, flowers, and strawberries.

There are also three golden line-fillers found on the right-hand side of the text. Initially popularized by early Irish manuscripts, these were used to help create visual balance by filling in blank spaces that were not occupied by script.

Reference – MS 5650/54

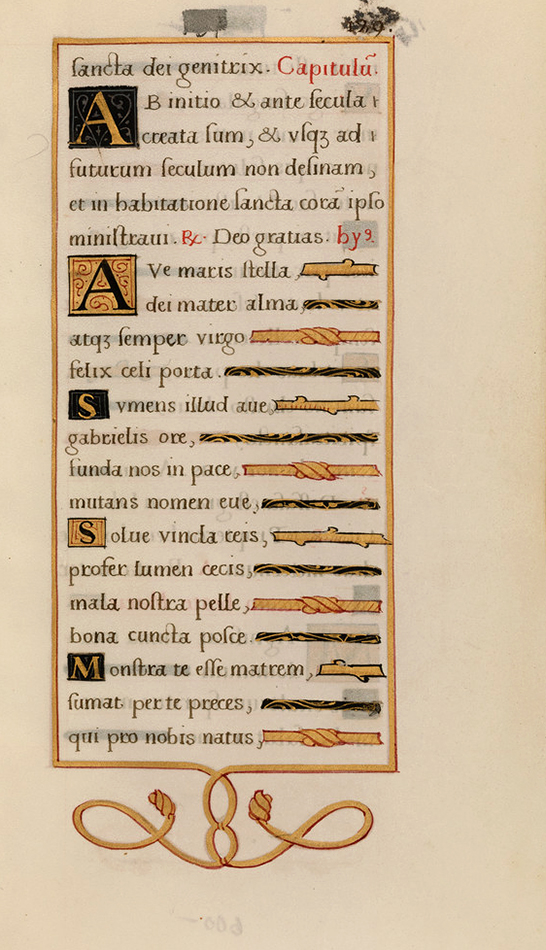

Leaf from a Book of Hours (c.1530)

[Script: Humanist]

Written in Latin, produced in France

An important feature for every book of hours was a set of prayers and psalms dedicated to Mary, the Mother of God. These were known as the The Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or the Hours of the Virgin.

This was service of worship which was divided into eight prayers, with each section recited at fixed intervals throughout the day. These were Matins (recited before daybreak), Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext (at around noon), None, Vespers, and Compline (recited after sunset).

This example shows part of the hymn ‘Hail, star of the sea’ from Vespers, as well as the start of the Magnificat, also referred to as the Song of Mary.

Reference – MS 5650/53

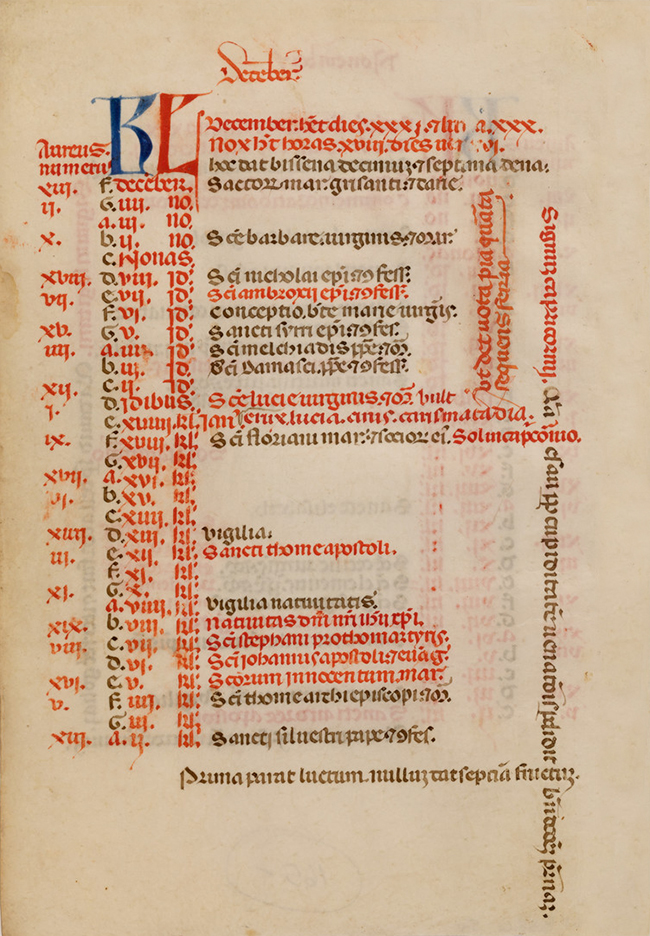

Leaf from a Psalter (c.1350)

[Script: Southern Textualis Formata (Rotunda)]

Written in Latin, produced in Italy

A psalter is a volume containing the Book of Psalms, a group of 150 songs from the Bible. They were often produced together with a liturgical calendar and litany of the Saints.

The psalter was the most widespread prayer book before the development of the breviary and the book of hours a few centuries later. Psalters were usually owned by wealthy lay people, and were commonly used for learning how to read.

Shown here is a leaf from a liturgical calendar from the month of December. Liturgical calendars were used to determine when holy days such as feast days were observed, with prominent days such as Christmas listed in red.

These ‘red letter days’ can be useful for giving insight into the manuscript’s original owner, as they would often highlight holy days that held the most personal significance.

Reference – MS 5650/50

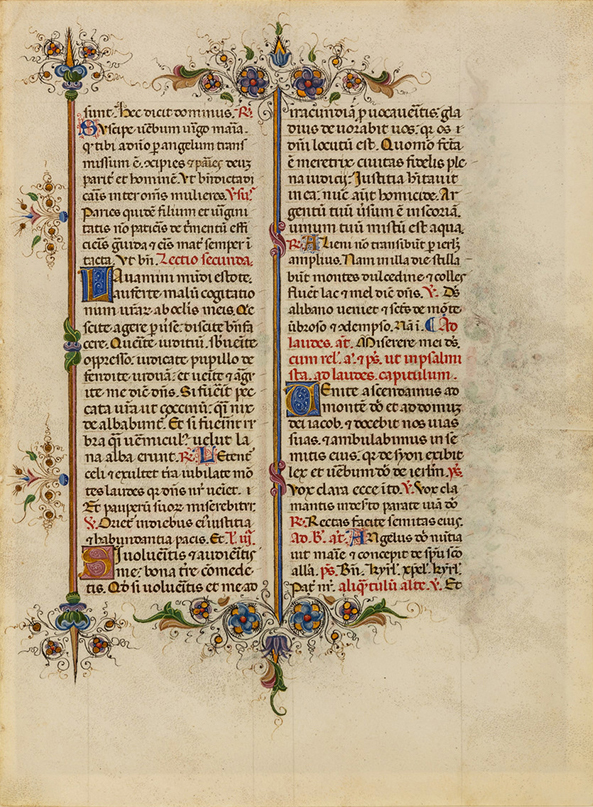

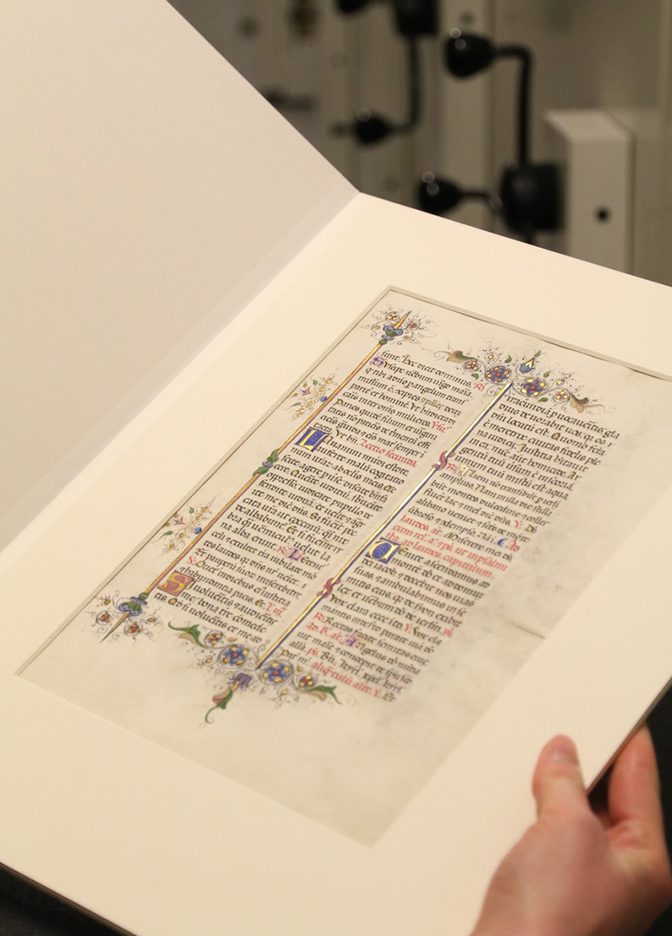

Leaf from a Breviary (c.1441-1448)

[Script: Southern Textualis Formata (Rotunda)]

Written in Latin, produced in Italy

Evolving from the psalter, the breviary began to be produced in around the 12th century, with the book of hours following roughly a century or so later. Like the book of hours, a breviary contained an eight-part daily set of prayers, known as the Divine Office.

This breviary was likely made for Leonello d’Este, a Duke of the Italian province of Ferrara in the mid 15th century, who was renowned for his sponsorship of the arts.

Though religious volumes were often created for use in monasteries, heavily illuminated versions were also used as signs of status by wealthy patrons, such as members of the nobility. They could also be commissioned by rulers as diplomatic gifts.

Reference – MS 5650/59

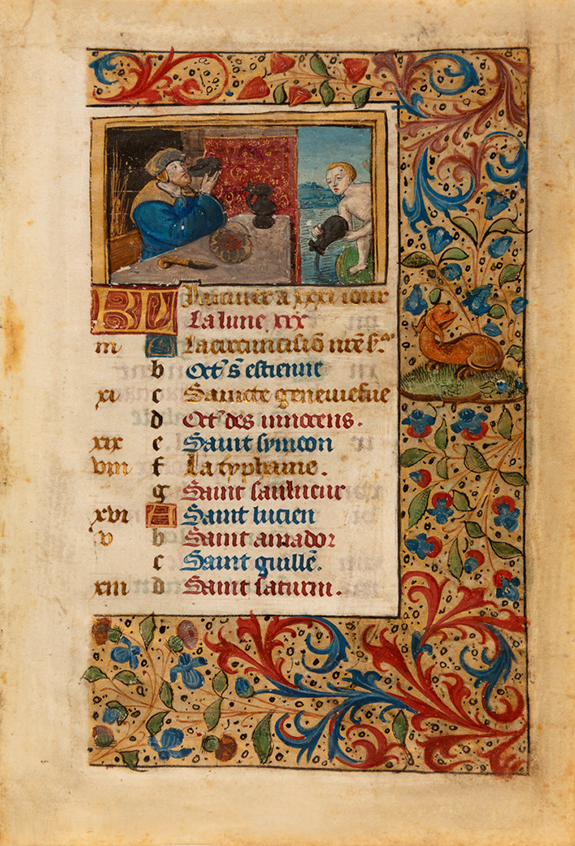

Leaf from a Book of Hours (c.1480)

[Script: Textualis Formata (Textus Quadratus)]

Written in French, produced in Northern France

This leaf taken from a French book of hours shows a rather extravagant example of a liturgical calendar, this time from the month of January. Prominent holy days are listed in gold.

The independent illumination found above the calendar, known as a miniature, is typical for a book of hours in that it shows two important features related to the medieval calendar: the labour of the month, along with its associated zodiac sign.

January’s labour is often associated with feasting. The man on the left is shown seated at a table and drinking wine, accompanied by a jug, bread and a knife. On the right a naked youth, the zodiac sign of the water carrier Aquarius, pours water from a jug into a river.

Reference – MS 5650/40

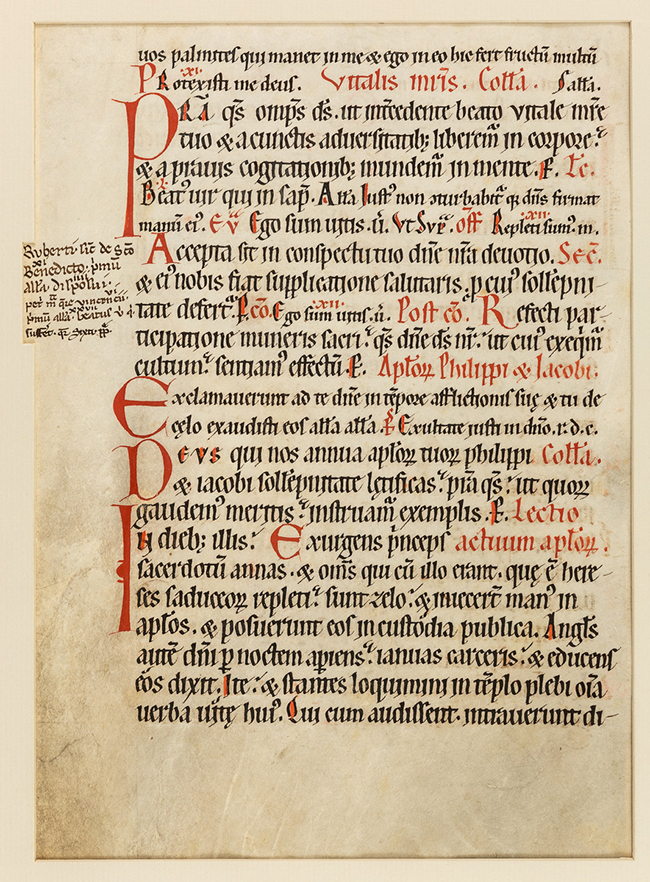

Leaf from a Missal (c.1150-1180)

[Script: Praegothica]

Written in Latin, produced in Southern Germany/Austria

Some manuscripts were not permitted to be quite as flamboyant. This example, taken from a Cistercian missal, includes verses from John Chapter 15, as well as the responses for the feast of Saint Philip and Saint James.

Missals were an integral part of day-to-day life in medieval churches as they contained all the instructions and texts necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the year.

Monasteries often had a special room, known as a scriptorium, where manuscripts were made by scribes. However, Cistercian monks implemented strict rules when creating their own texts. They were not allowed to be embellished with paint or gold, as it was considered a distraction from devotion.

Reference – MS 5650/47

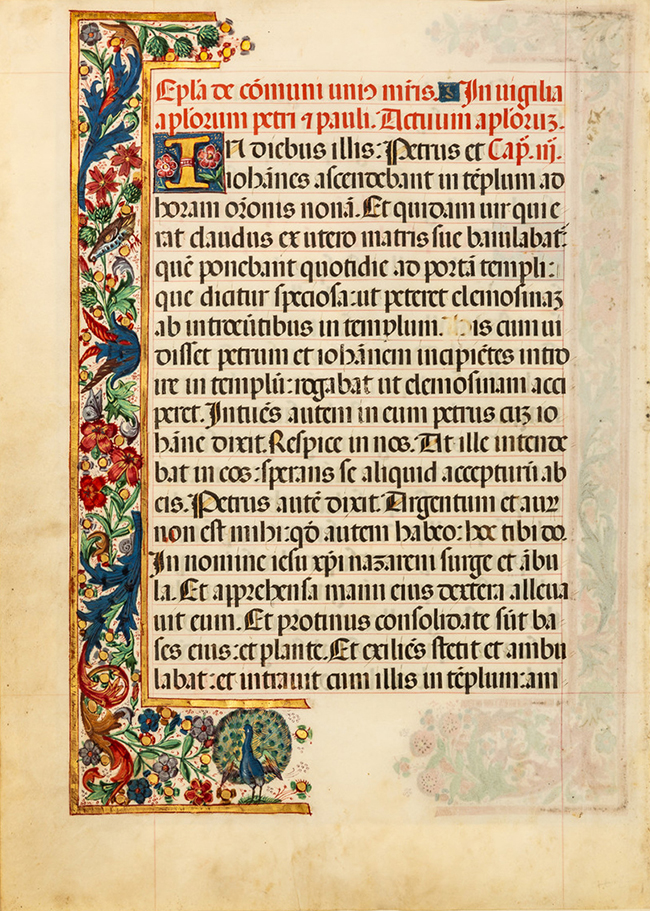

Leaf from a Lectionary (c.1500)

[Script: Iberian Textualis Formata (rotunda)]

Written in Latin, produced in Spain

A lectionary is a book that contains a selection of scripture readings from the Bible, made to be read during public worship on specific days. This leaf shows part of Isaiah Chapter 49, part of Revelation Chapter 7, and part of the Acts of the Apostles Chapter 3.

The intricately decorated border shows a host of flora and fauna – flowers, acanthus leaves, a peacock, a bird, a butterfly and even a small snail appear along the side.

Animals were a frequent feature in religious manuscripts to the point where they even had their own dedicated book, known as a Bestiary. Many of them had their own symbolic meanings – the peacock, for example, symbolised immortality and eternal life.

Reference – MS 5650/65

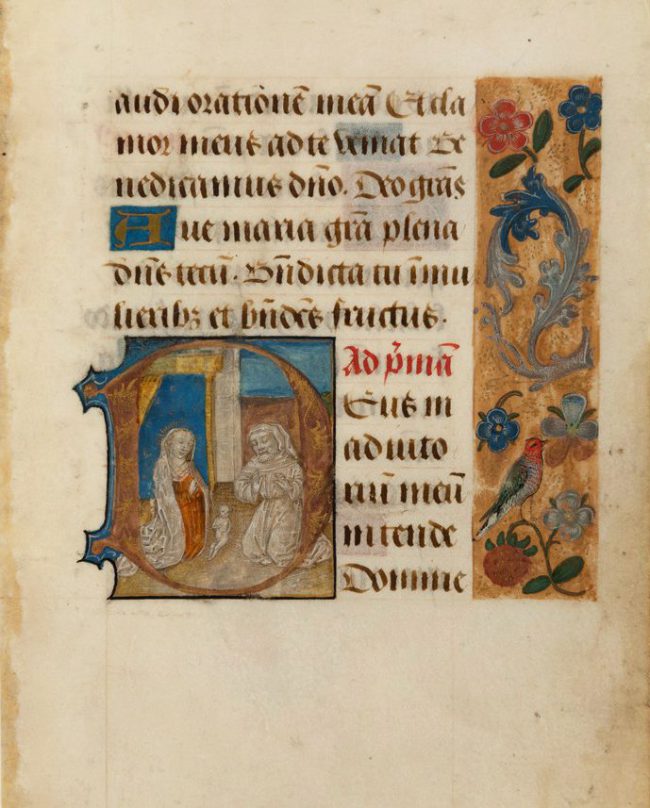

Leaf from a Book of Hours (c.1470-1480)

[Script: Bâtarde]

Written in Latin, produced in Hainaut, Belgium

An initial is a letter found at the beginning of a word, sentence, or paragraph that is larger than the rest of the text. Heavily-decorated initials were a common feature in manuscripts, as they were often used as a means of highlighting important sections of script. Some included depictions of important figures and events relevant to the text using a special type of illumination known as a historiated initial.

This leaf from a Belgian book of hours shows a meticulously illustrated letter ‘D’, and is an excellent example of a historiated initial as it depicts Mary and Joseph with the baby Jesus.

This illumination would have been particularly pertinent to this section of text, as it comes from the Hours of the Virgin at Prime.

Reference – MS 5650/136

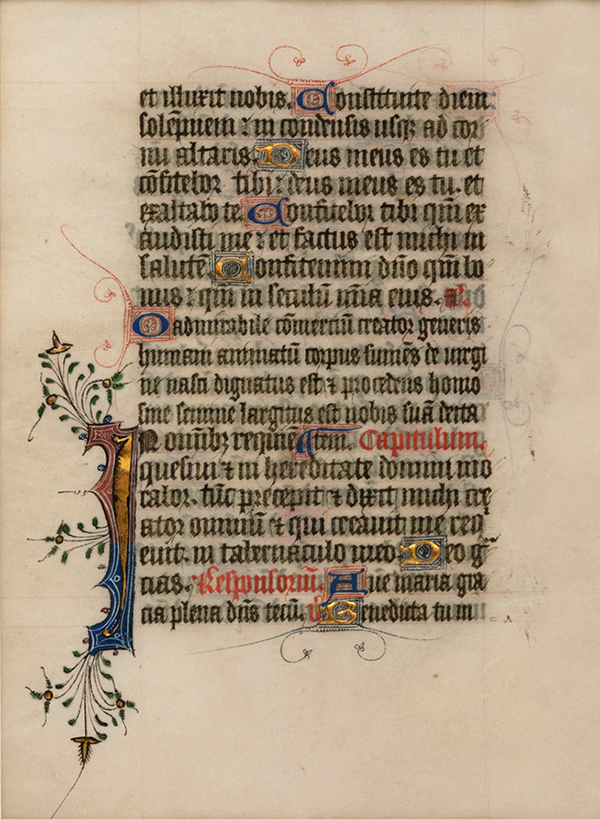

Leaf from a Book of Hours (c.1470-1480)

[Script: Textualis Formata (Textus Quadratus)]

Written in Latin, produced in England

Initials could also be embellished without the use of detailed scenes and figures, as seen from this English book of hours from around the same period.

Like many illuminated manuscripts, gold has been added to the large ‘I’ to give it even more emphasis; a technique known as gilding. This could be applied as an ink, but was more often applied using gold leaf and a binding medium such as glue or gum. A colorant such as bole was sometimes added to help boost the gold’s luminance.

This leaf is likely from the Hours of the Virgin, and shows Verses 16 to 29 of Psalm 117.

Reference – MS 5650/133

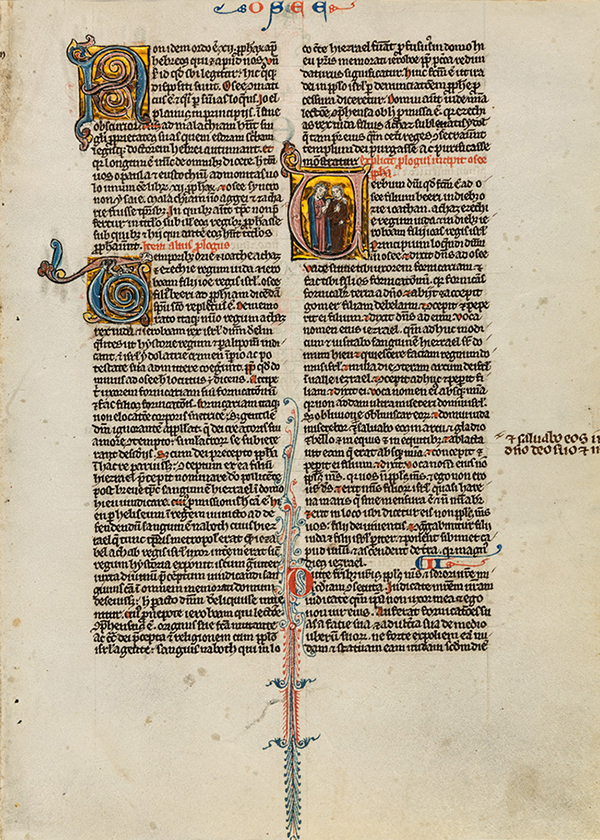

Leaf from a Bible (c.1250)

[Script: Textualis Libraria (Textus Semiquadratus)]

Written in Latin, produced in Paris, France

A bible is a collection of sacred texts and scriptures. The Christian Bible, consisting of the Old and New Testaments, is a fundamental aspect of Christian teaching.

This example shows a section from a Parisian Bible, telling a story of the prophet Hosea. This is evidenced by the inscription of his name (written here as ‘Osee’) at the top, as well as the historiated initial ‘V’ in the right-hand column, depicting Hosea embracing his new wife, Gomer.

There is also a dragon situated in the letter ‘T’ in the lower part of the left-hand column. Though they were not always relevant to the text, dragons were a frequent source of inspiration when decorating medieval manuscripts.

Reference – MS 5650/37

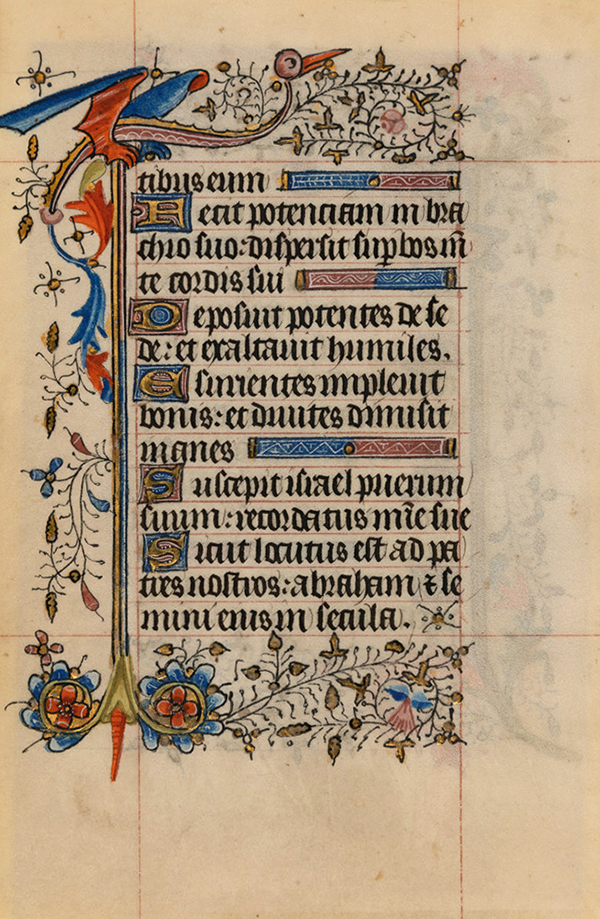

Leaf from a Book of Hours (c.1420)

[Script: Textualis Formata (Textus Quadratus)]

Written in Latin, produced in Normandy, France

A brightly coloured dragon is found perching above this text from Luke Chapter 1, verses 46 to 55, this time with a bird’s head.

A medieval illuminator’s palette was surprisingly large. Pigments were obtained from a wide range of sources – reds such as crimson and carmine were extracted from insects, and the widely sought-after ultramarine blue was made using lapis lazuli from Afghanistan.

As these usually took the form of powders, binding agents were used to help apply the pigments to the page. They could be made from egg yolk, sugar, or even ear wax.

Ruling lines were also added for visual guidance. This leaf has lines drawn in red ink across the page in order to help the scribe and the illuminator place their work accurately.

Reference – MS 5650/26

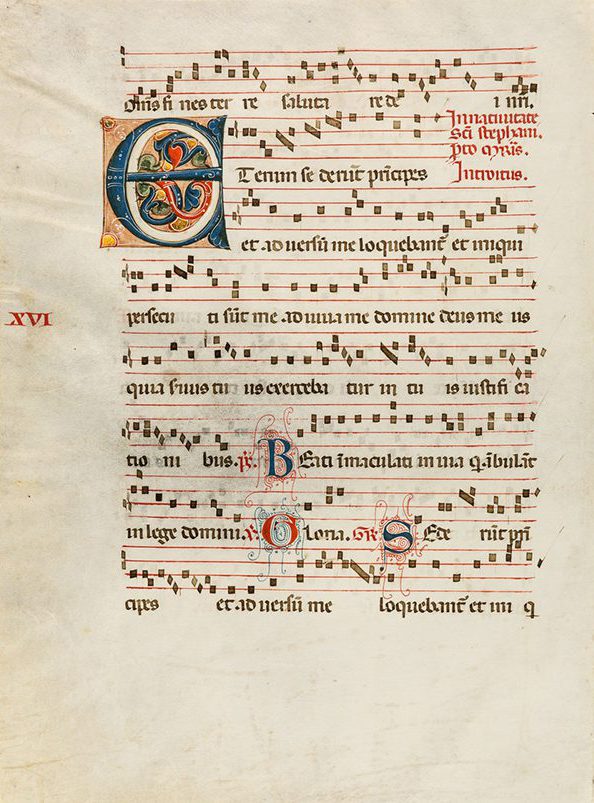

Leaf from a Gradual (c.1300)

[Script: Southern Textualis Formata (rotunda)]

Written in Latin, produced in Italy

A gradual is a choir book that compiles chants for singing in the Mass, with this leaf showing part of a hymn to be sung on the nativity of Saint Stephen.

The manuscript has a four-line stave ruled in red, rather than the standard five-line stave we see today, as this was a type of musical notation often associated with Gregorian chant.

This leaf is unusual in that it is of an intermediate size – not large enough for a large group of singers, but nor is it small enough to be used for personal devotions.

Reference – MS 5650/66

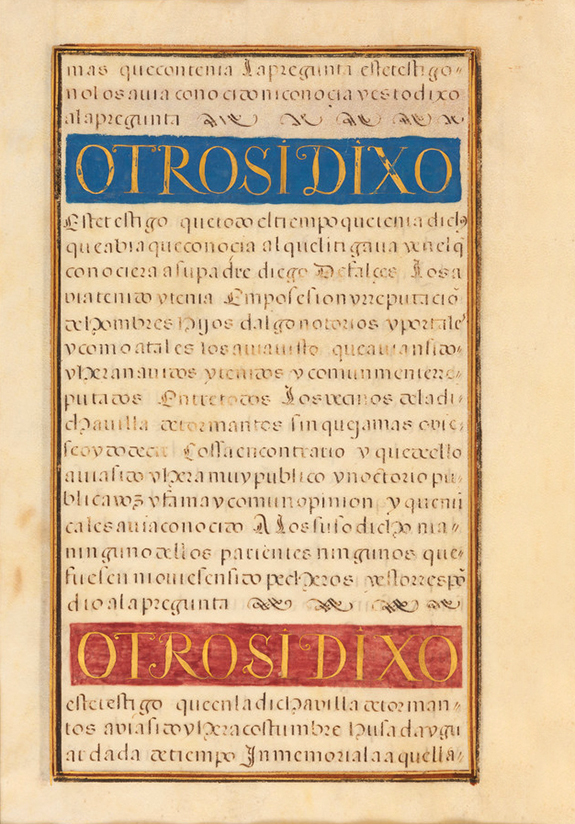

Leaf from a Carta Executoria de Hidalguia (c.1600)

[Script: Iberian Textualis Formata (rotunda)]

Written in Spanish, produced in Italy

The leaf presented here is likely from a Spanish Carta Executoria de Hidalguia – an important genealogical document during the medieval period, as it established family lineage and therefore could potentially provide evidence of nobility.

A Carta was often authenticated by civic or ecclesiastical authorities, and the benefits of owning one included exemption from taxation in return for military service.

The text here refers to persons living in Northern Spain, and residing in or near the towns of Logroño and Tormantos.

Reference – MS 5650/126

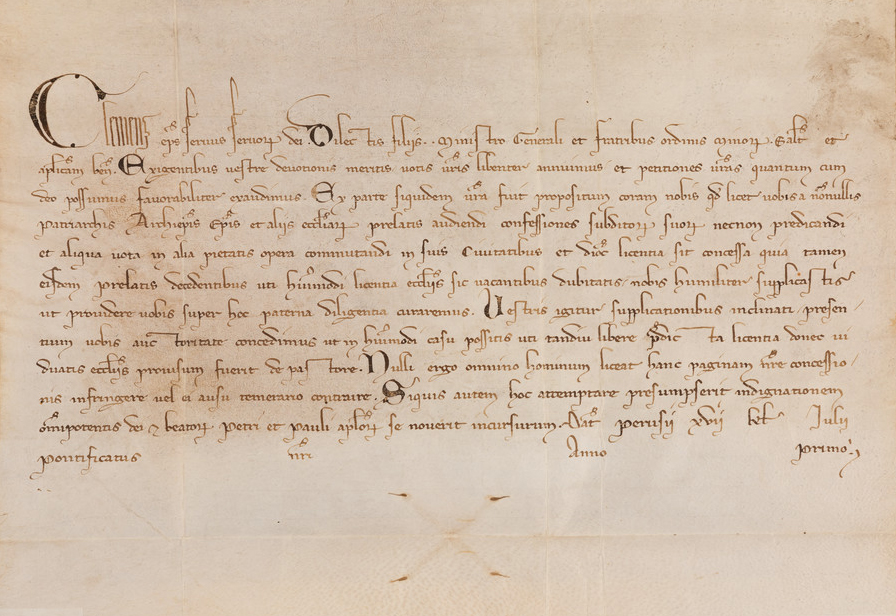

Leaf from a Papal Bull of Pope Clement IV (15 June, 1265)

Written in Latin, produced in Perugia, Italy

A papal bull is a type of public decree issued by a pope of the Roman Catholic Church. It is named after the lead seal, taken from the Latin word bulla (meaning ‘bubble’ or ‘blob’), that was traditionally attached in order to properly authenticate it.

This document lacks its bulla, which most likely would have been attached by silk threads. The four slits and the plica fold in the vellum can still be seen, marked by the ‘X’ at the bottom.

This bull was sent from Pope Clement IV to the monks of the Franciscan order, granting them the privilege to preach and to hear confessions when the archbishop seat was vacant.

Reference – MS 5650/132

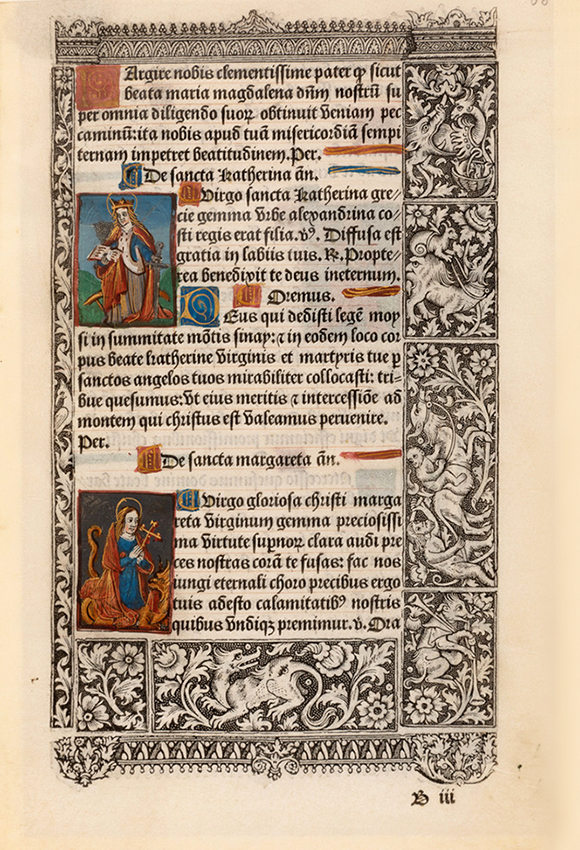

Leaf from a Book of Hours (1506)

[Script: Cursive Formata (Bastarda)]

Written in Latin, produced in Paris, France

After the introduction of the printing press in around 1455, texts became much easier to mass produce.

This leaf was not handwritten, but printed by Antoine Vérard, a Frenchman who began printing in 1485. Vérard was the first to print a Book of Hours, and his work set a standard of elegance for French book production, later attracting patrons such as Charles VIII of France and Henry VII of England.

The text shows short prayers, known as suffrages, to Saint Katherine and Saint Margaret. These are accompanied by their miniatures on the left-hand side.

Reference – MS 5650/64

Discover More

This exhibition demonstrates just a small fraction of the 143 manuscripts currently held by the University of Reading. Click here to visit our A-Z pages and learn more about our collection.