Uprooted

Exploring archival stories of forest conservation

Concern over deforestation has been documented in the Kew archives for over 150 years. In this display, we uncover histories of forest loss and conservation in Kew’s collections, through the stories of four trees. Each links different collections from across Kew to reveal how trees were used unsustainably around the colonial world – from harvesting timber and resin to creating pieces of clothing and art.

Our title for the exhibition represents the act of deforestation, but also the transfer of trees and forestry methods across the British Empire under the guidance of Kew in the 19th and early 20th centuries. We sought out these more unusual stories in the archives to reveal how cultural histories and botanical research in each of these places eventually informed forest conservation practices and have offered us lessons in caring for nature.

Today, global biodiversity loss, climate change, and ecological resilience occupy our thoughts and play a critical part in all of Kew’s current scientific work and community partnerships. Explore kew.org and https://www.kew.org/science/state-of-the-worlds-plants-and-fungi

to see examples of Kew’s current conservation work and read our blog post about the exhibition here: https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/uprooted-forest-change

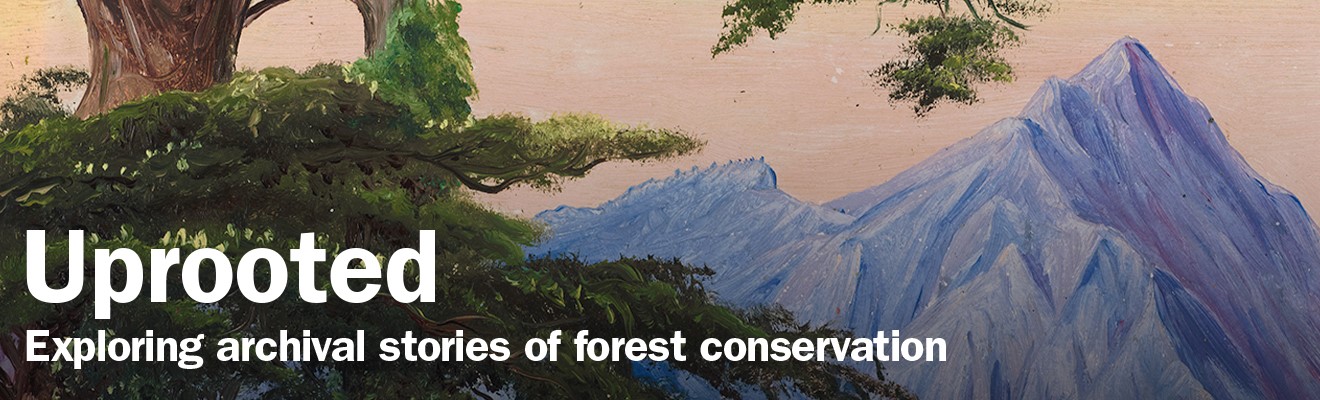

1. The Forest Flora of New Zealand

Thomas Kirk

Wellington: Govt. Printer, 1889

This stark image of timber extraction conveys the enormous loss of endemic kauri trees from the northern forests of New Zealand in the 19th century. Native kauri forests once stretched for over 1.2 million hectares and kauri was used by Māori communities for canoes (waka), construction and cultural carvings. Kauri timber became valued by Europeans for ship’s masts and spars but also a wide range of other construction uses. As well as these pictured ‘rolling roads’, impressive ‘driving dams’ were engineered by loggers to help transport kauri timber downstream using the power of water.

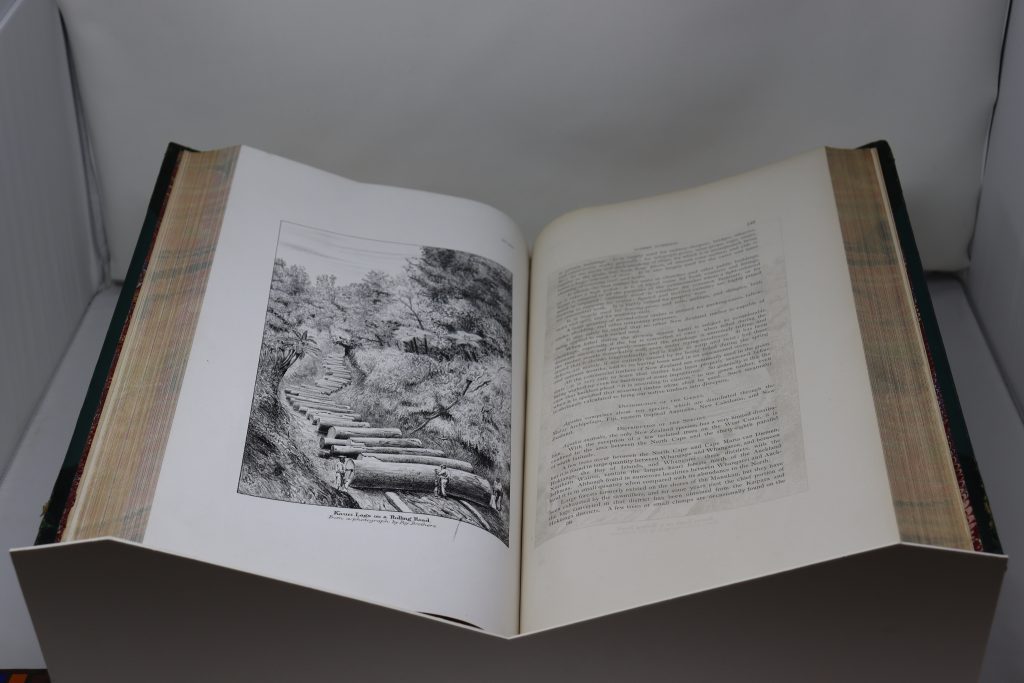

2. Sketch Map of Teak Localities in British Burmah

From ‘Progress Report of Forest Administration in British Burmah’, 1861-62

Miscellaneous Reports, India Forests, MCR/5/1/56

In colonial India, the forest resources of different regions were surveyed to allow British officials to assess natural timber resources for commercial and strategic interests. This map of teak forests was completed in 1863, the year before the new forest department for British India was set up. This department eventually managed a fifth of the subcontinent and foresters held a huge amount of power over the landscape. This map is included in a volume from Kew’s Miscellaneous Reports, an archival collection containing materials relating to Kew’s colonial activities in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

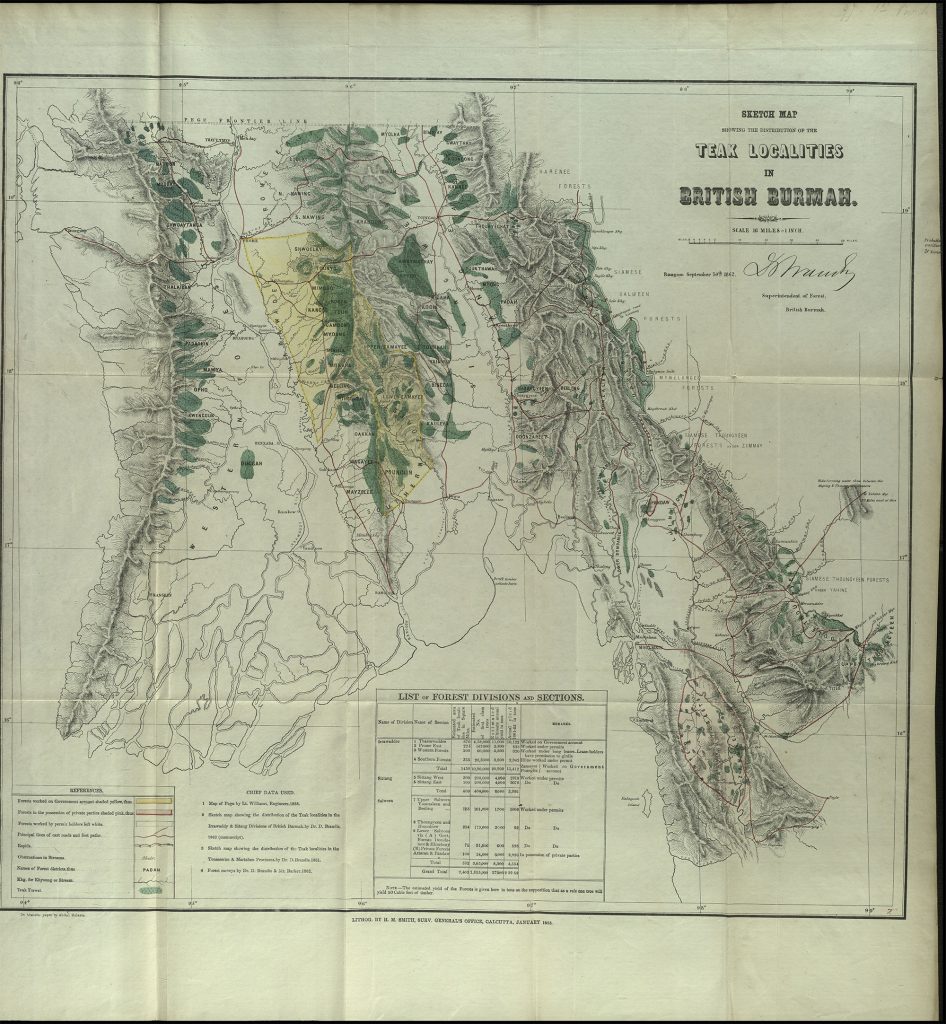

3. A Bush Fire at Sunset

Oil on board painting, early 1880s

Original on display in Kew’s Marianne North Gallery

The Victorian painter Marianne North travelled the world in the late 19th century, capturing the plants, nature and landscapes that surrounded her. In Queensland, Australia, she also painted this response to the aftermath of a bushfire and the devastation of natural forest. In her autobiography she remembered ‘The hills were on fire, and the foreground was black with a fire that was only just over…Stunted white stemmed trees were dotted about and not a flower was to be found.’ Recollections of a Happy Life, vol. 2. p.121

4.

1. Teak sample, Tectonia grandis 2. Lacebark doyley, Lagetta lagetto

3. Kauri gum, Agathis australis

Economic Botany Collection, 13948; 97891; 31026

Find out how these three intriguing objects are related to deforestation throughout this exhibition. Kew’s Economic Botany Collection holds over 100,000 items related to the human uses of plants and was once housed in Kew’s four museums of economic botany.

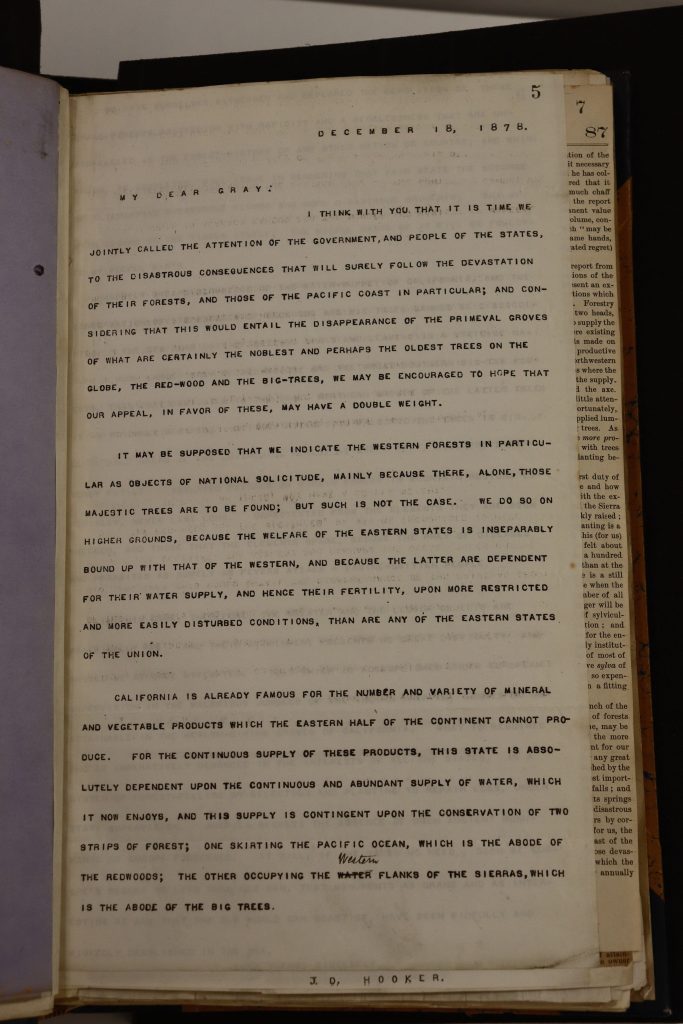

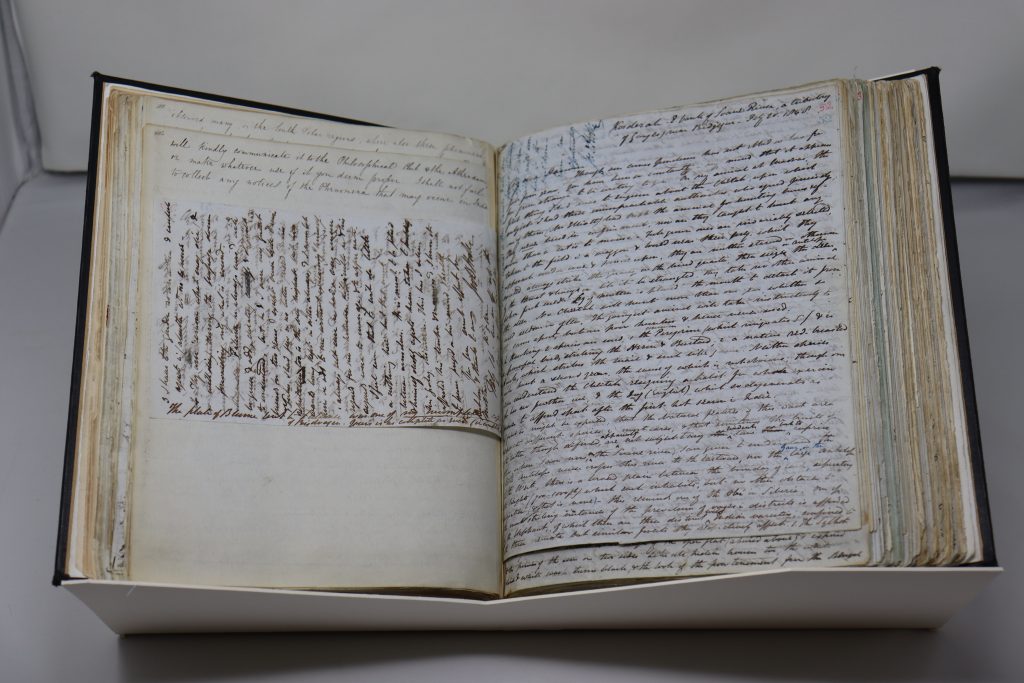

5. Letter from Joseph Hooker to Asa Gray, 18 December 1878

Miscellaneous Reports, United States: Forestry, MCR/13/4/2/5-6

This letter from Kew director Joseph Hooker to his friend, the American botanist, Asa Gray clearly displays his deep concern over deforestation. Hooker outlines many of what remain the key concerns around deforestation in the 21st century: water supply, soil fertility, timber supply, and the threat of extreme weather, but also the protection of trees as ‘ancient monuments’. He calls for methods of selective tree felling and replanting.

6. Man and Nature

George Perkins Marsh

London: Sampson Low, Son and Marston, 1864

American author G.P. Marsh (1801–1882) challenged the 19th-century understanding of the unlimited availability of natural resources and argued that human actions did impact nature. He warned of the effects of deforestation, using an example of an ancient civilisation declining as a result of environmental degradation. This book was hugely influential in its day and helped to inspire the early stages of modern conservation.

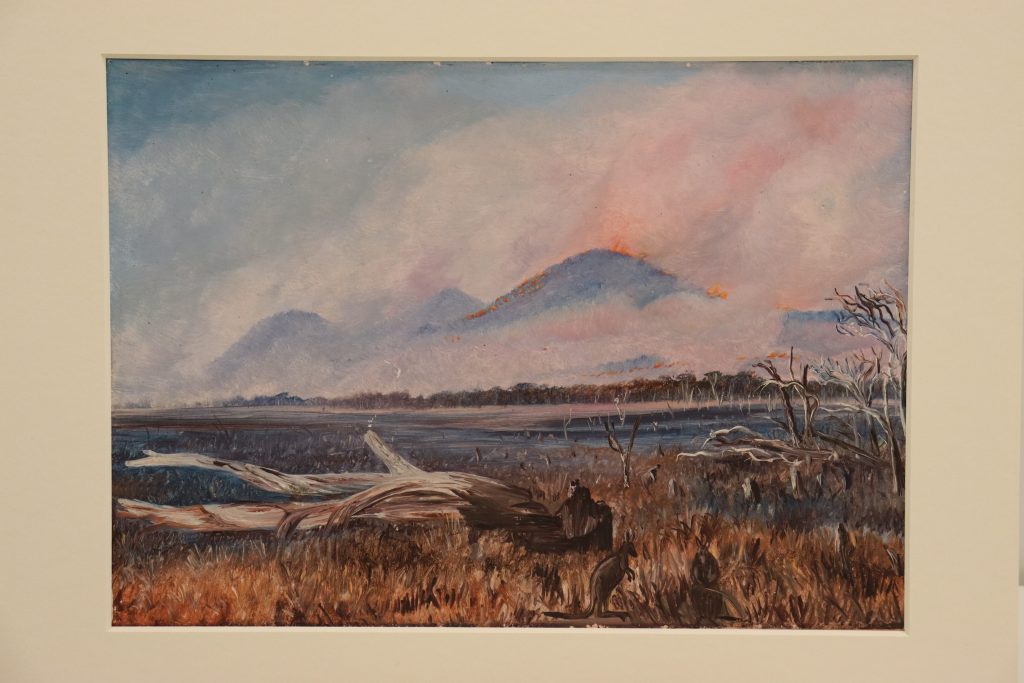

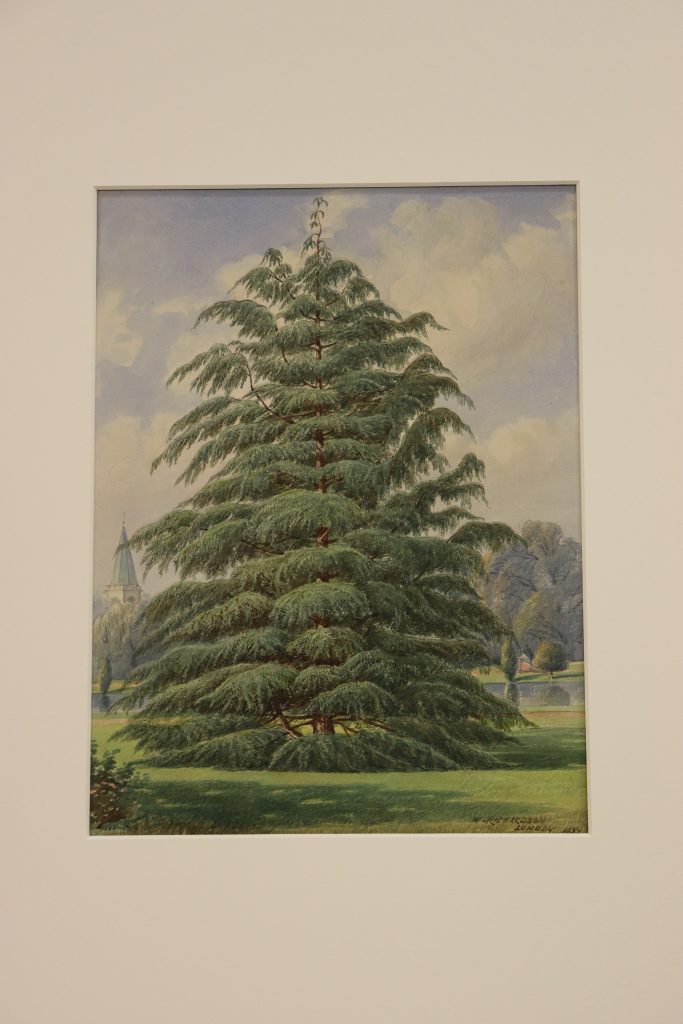

7. Cedrus deodara

Edward Ravenscroft

Original painting for The Pinetum Britannicum, vol. 3, 1884

The stately deodar cedar (Cedrus deodara) is an evergreen conifer native to the western Himalayan forests of northern India, Nepal, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Deodars (or devadāru, a Sanskrit word meaning ‘wood of the gods’) were greatly valued by local people for their strong, scented timber. Deodars were admired for their elegance and brought to Britain as ornamental trees from the 1830s and planted in landscaped gardens, such as at Kew. You can visit some 19th-century specimens here along the Broad Walk and around the Palm House.

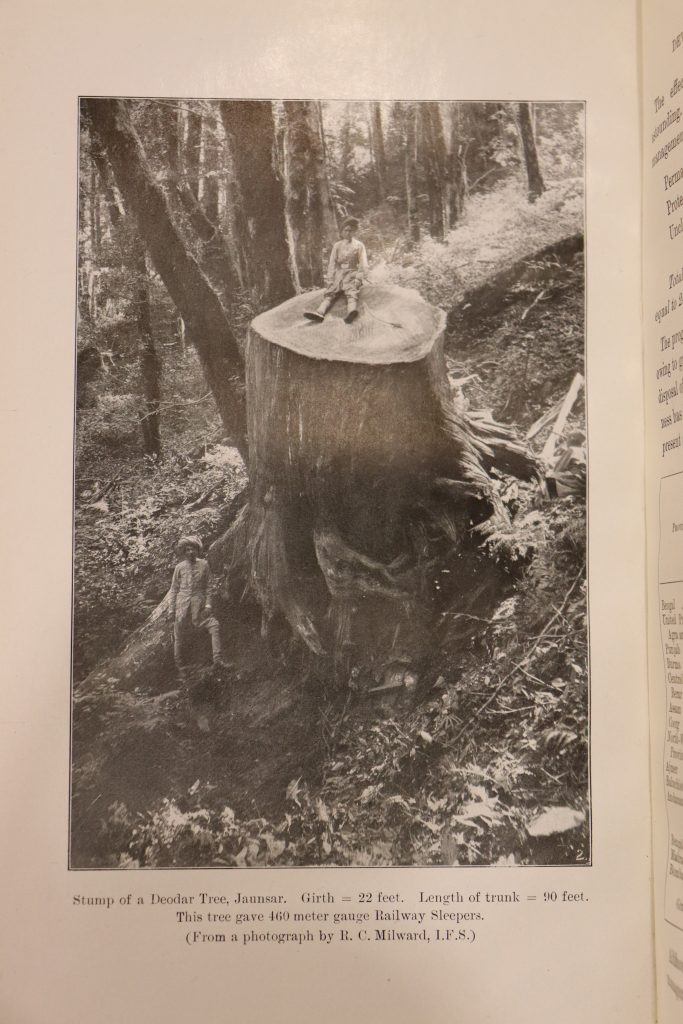

8. Schlich’s Manual of Forestry

by W. Schlich, vol. 1, 1906

9. Letter from Joseph Hooker to Charles Darwin, 2 February 1848

Kew Archives, JDH/1/10/52-54

In 1848, Joseph Hooker wrote to his friend Charles Darwin from Kosderah commenting on the deforestation he saw first-hand in India, its effect on the climate but also the wildlife, including crocodiles (see printed excerpt).

In reaction to such deforestation, the British Raj established the ‘Imperial (or Indian) Forest Department’ in 1864 to manage the long-term use of the forests. Its first priority was to assess the deodar forests and aid the production of more railway sleepers, but other trees were also managed for the production of varnishes, oils and resins, for tanning, medicines, and even the production of matches. In 1878, a new forest law brought many areas of non-privately owned forest under the compulsory control of the state.

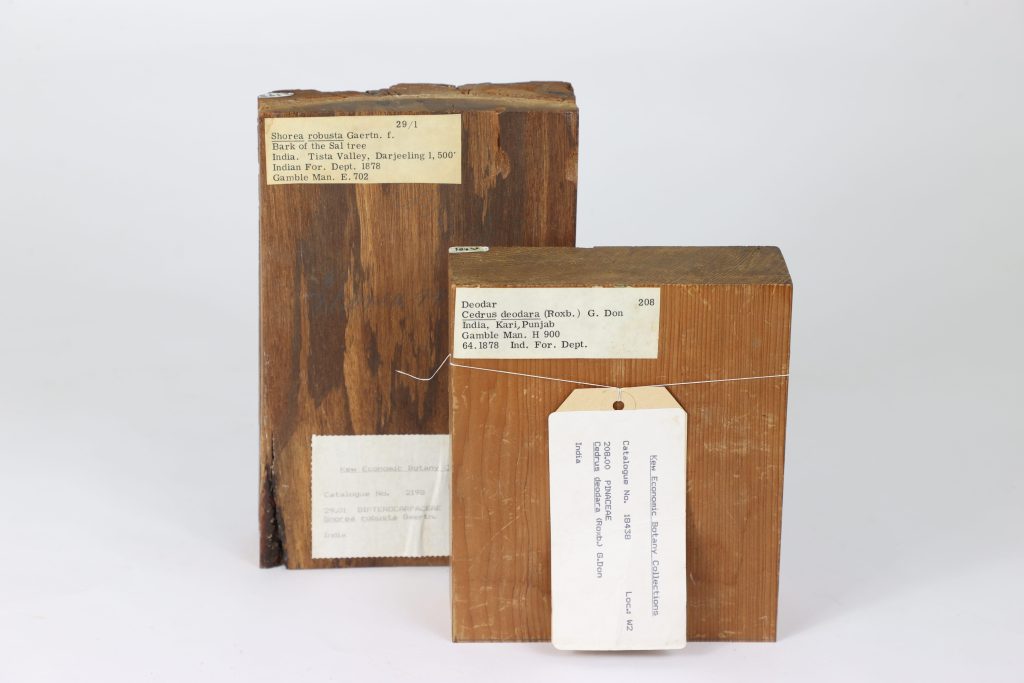

10.

1. Sal, Shorea robusta 2. Deodar, Cedrus deodara

Economic Botany Collection, 2198; 18438

The dense, pest-resistant Indian timbers of sal (Shorea robusta) and teak (Tectonia grandis) were the preferred hardwoods for making sleepers for the rapidly expanding British imperial railway network in India. Around 1,400 miles of railway track were being laid down each year by the late 19th century. The teak forests of the Malabar coast and Western Ghats were decimated by the need for timber for both the Navy and railways. Deodar (Cedrus deodara) wood became the favoured substitute and deforestation of the once seemingly ‘inexhaustible’ northern forests increased. Further conversion of land to tea plantations, as well as mining and smelting activities in the mid 19th century by the British, also decimated the deodar forests.

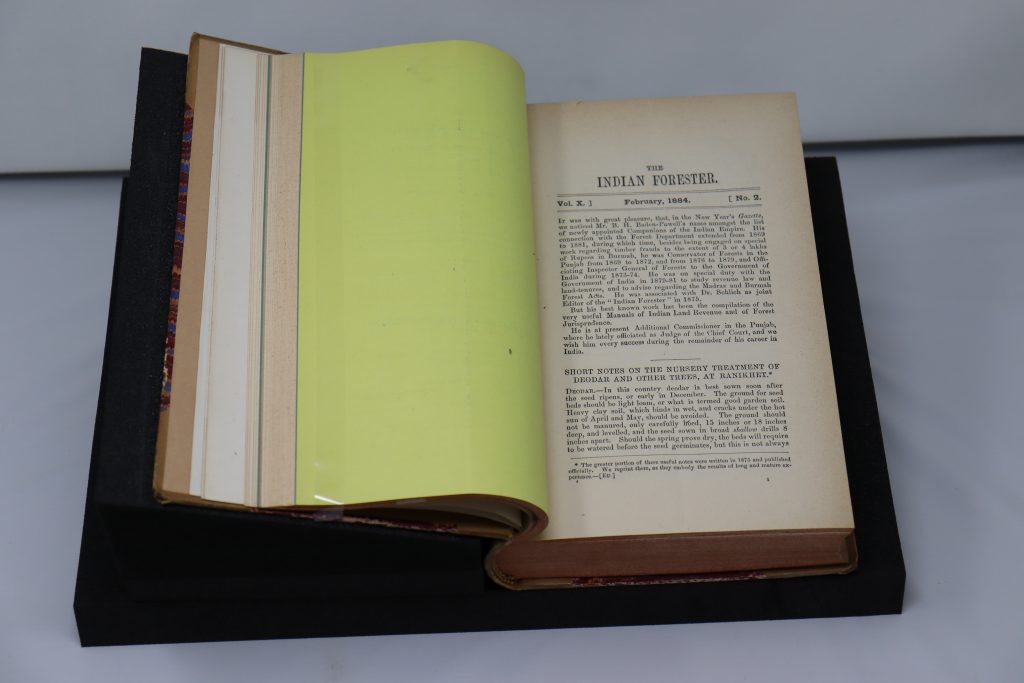

11. The Indian Forester magazine, February 1884

12. Progress of Forestry in India by Dietrich Brandis, 1884

As well as surveying forests, producing annual reports, creating floras and an herbarium, the Indian Forest Department implemented replanting schemes and helped develop the new forestry school and research institute at Dehra Dun in 1906, where Indian men trained as junior forest officers. Magazines such as The Indian Forester also printed wide-ranging articles – from advice on deodar propagation, to updates on forest laws.

Although such laws were successful in conserving certain types of trees, they prevented traditional subsistence access for timber, fuel and grazing etc. This led to large-scale vegetation and ecological change within the forests. Indian forestry was lauded by some as an exemplar of ‘scientific forestry’ which influenced forestry around the world – from Australia to the USA. However, it was also reviled as a point of huge social unrest and injustice to local people, as well as contributing to famine and disease, sparking public uprising against colonial rule. Today, Himalayan forests face continued pressure from land-use change and climate change, meaning that deodars are still under threat.

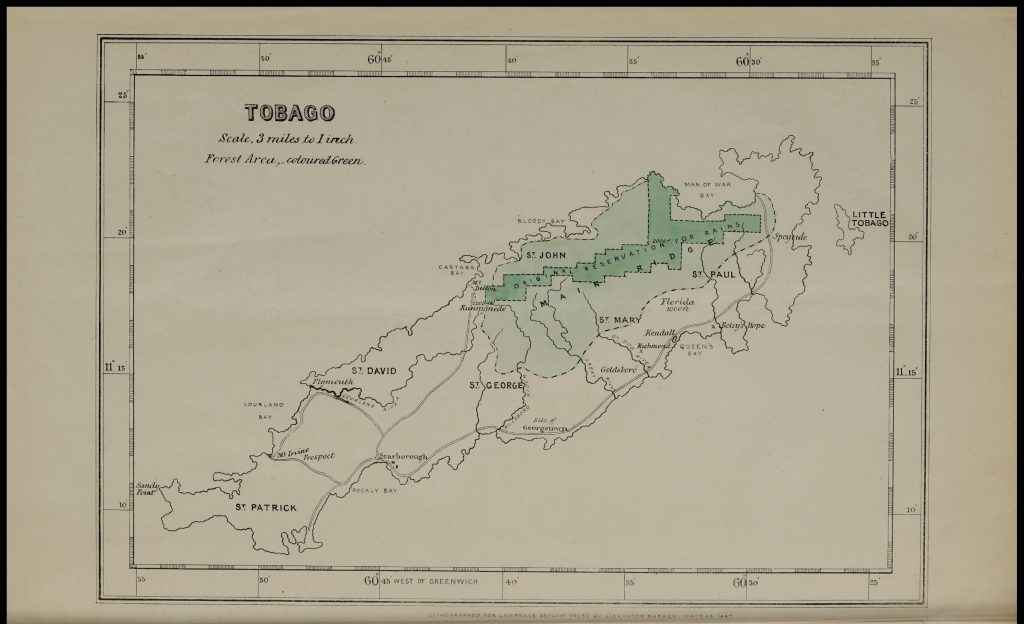

13. Map of Tobago

From Report Upon the Forests of Tobago, by E.D.M Hooper, 1887

Miscellaneous Reports, West Indies: Forests, MCR/15/1/6

In the Caribbean, forest conservation received little attention until the late 19th century, though forest reserves on the islands of Tobago and St Vincent were some of the earliest created explicitly for climate and rainfall conservation purposes. This map which shows a forest ‘reservation for rains’ is accompanied by a report on Tobago’s forests, written in 1887 by E. D. M. Hooper along with a series of similar reports from across the British Caribbean.

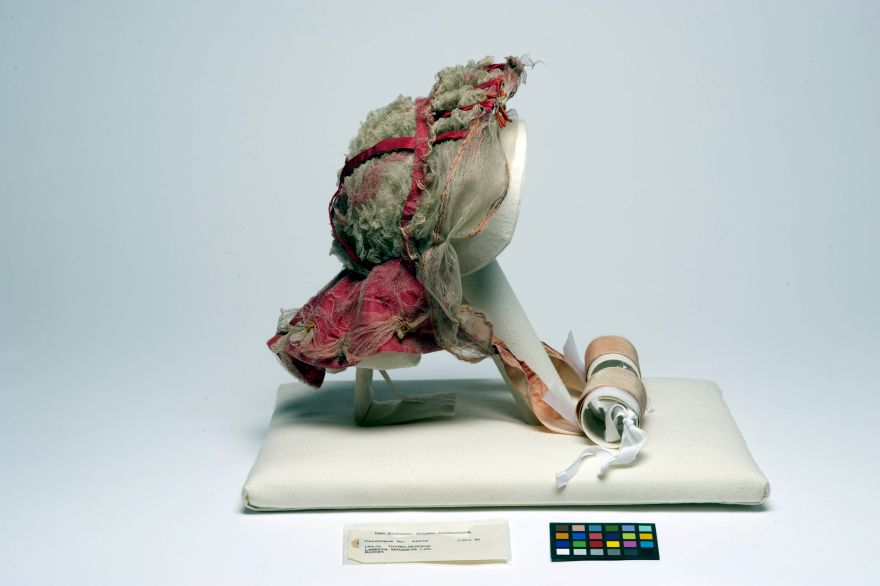

14. Lacebark bonnet

Lagetta lagetto

Economic Botany Collection, 44939

The forested limestone mountains of Jamaica are home to the

lacebark tree (often known as L. lintearia in the 19th century). The tree was once prized for its lace-like inner bark which was used to create intricate adornments such as the bonnet held here in Kew’s Economic Botany Collection, alongside more functional products like rope and whips. This bonnet was the focus of a conservation project by Emily Brennan, and has, along with the other lacebark items in the collection like the doyleys shown in the first window, inspired ongoing research into the tree’s history. Lacebark was used by enslaved women in Jamaica to create clothing, as well as by the descendants of those who escaped enslavement living in the Maroon communities of the Cockpit Country. Deforestation of this area and unsustainable harvesting practices led to the decline of the lacebark tree in the 19th century.

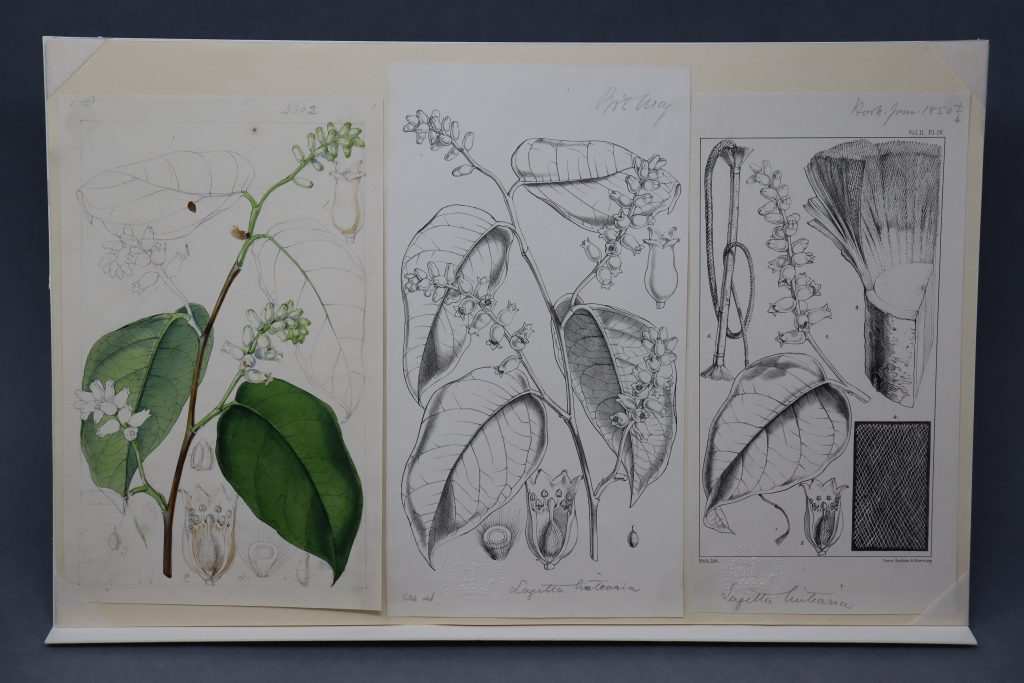

15. Lacebark tree (Lagetta lagetto), 1850

Walter Hood Fitch (1817-1892)

These illustrations show lacebark tree specimens in Kew’s Museum of Economic Botany and were reproduced in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. The panel on the right was reproduced in Hooker’s Journal of Botany and Kew Garden Miscellany, vol. 2. It includes a branch of the tree, highlighting how lacebark was extracted and stretched to form a lace, unlike other barkcloths which are beaten to reach the desired form.

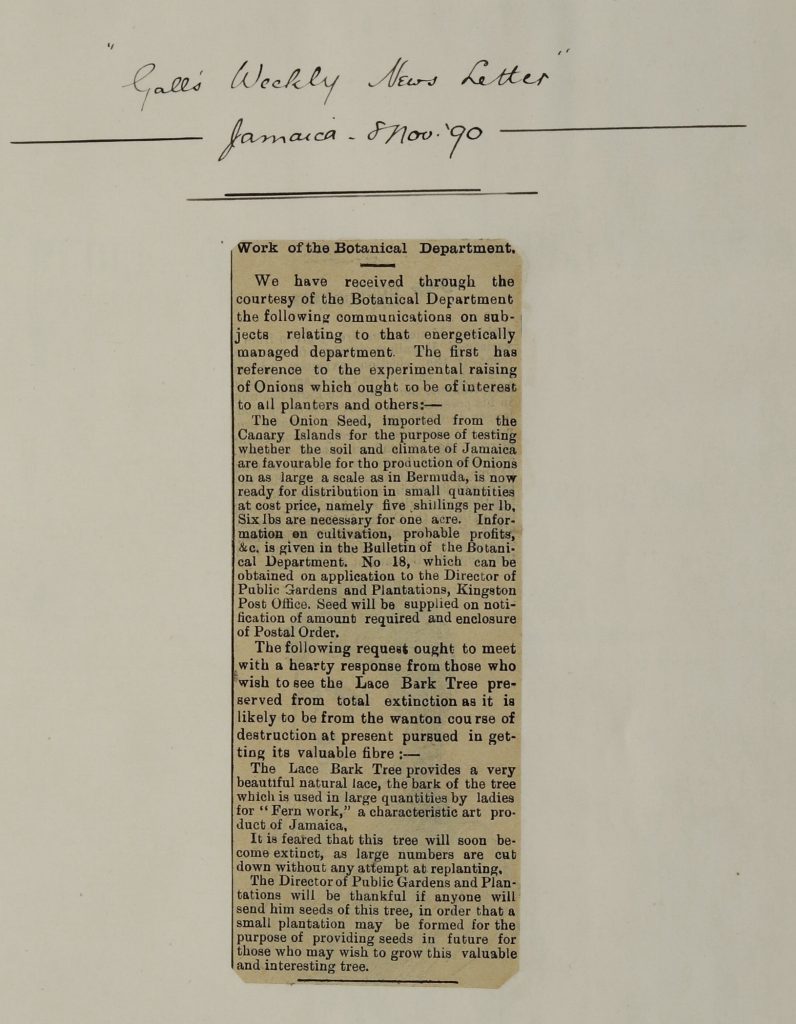

16. News cutting from Gall’s Weekly Newsletter, 8 Nov 1890

Miscellaneous Reports, Jamaica: Botanic Garden, MCR/15/3/5

William Fawcett (1851-1926), Director of the Jamaican Botanical Department, submitted this public plea for seeds of the lacebark tree in 1890, fearing that the tree would soon become extinct due to the scale of cutting and lack of replanting. Lacebark declined in popularity in the 20th century, and though attempts at revival the industry were made in the 1980s and more recently, these face the challenge of bringing the tree into sustainable cultivation.

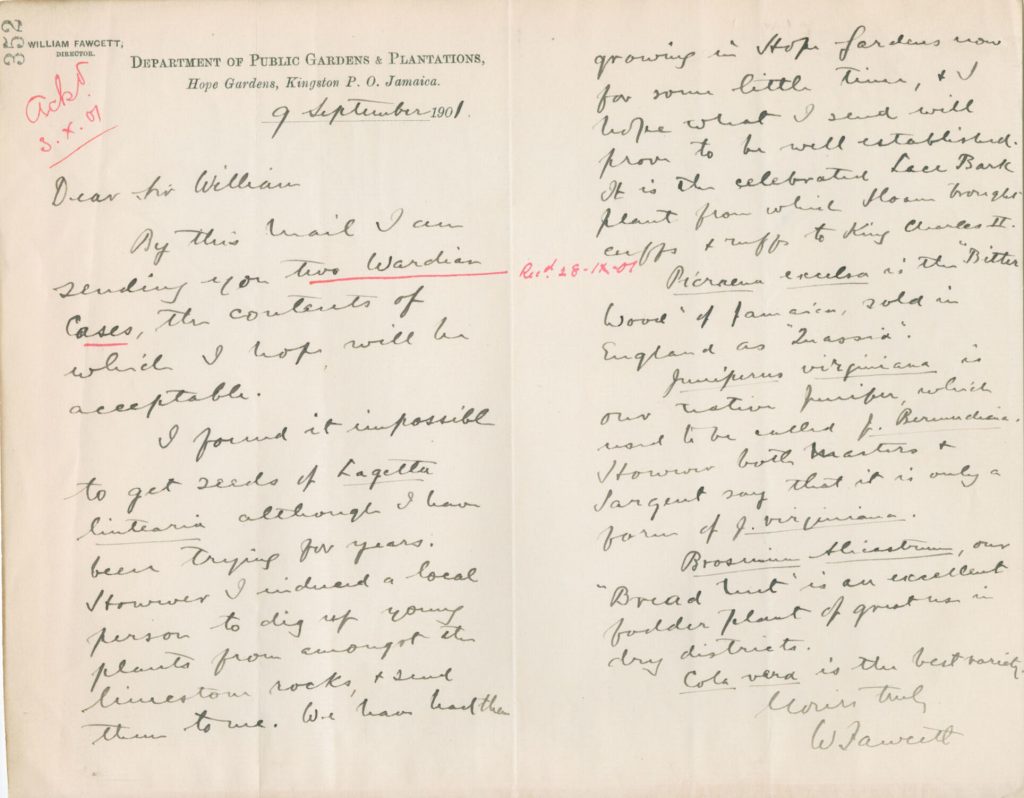

17. Letter from William Fawcett to William Thiselton-Dyer, 9 Sept 1901

Directors’ Correspondence, 208/352

Fawcett later wrote to Kew’s director William Thiselton-Dyer from Hope Gardens, Kingston, Jamaica in 1901 about the scarcity of the tree and impossibility of finding seeds to send to Kew. However, he adds that he has been able to plant lacebark at Hope Botanical Gardens in Kingston, Jamaica. Fawcett emphasises the tree’s royal renown, as the plant from which naturalist Hans Sloane ‘brought cuffs and ruffs to King Charles II.’

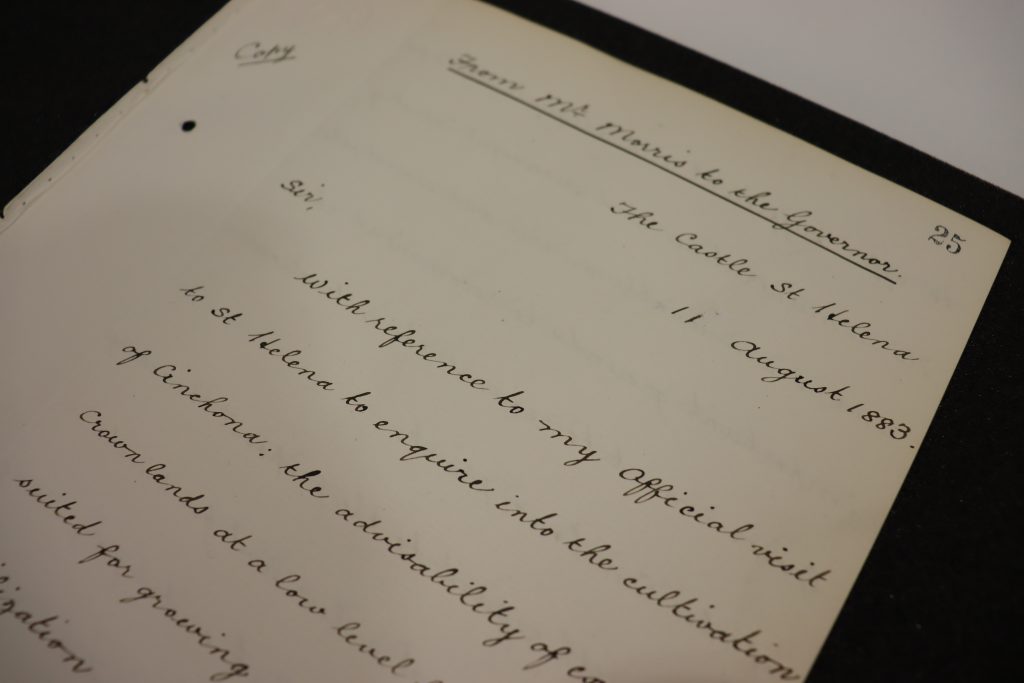

18. Report on a visit to St Helena

Daniel Morris

Miscellaneous Reports, St Helena: Miscellaneous, MCR/10/1/2/25-26

On a visit to St Helena in 1883 to examine the feasibility of cinchona cultivation on the island on behalf of the Colonial Office, Daniel Morris, (1844-1933) director of the Jamaican botanical department, instead took the opportunity to promote the protection of the forests and encourage reboisement, (reforestation), underlined in the pages here. He included a list of suggested trees and recommended that the boundary ridge on Diana’s Peak ‘should be permanently maintained in forest; and where at present denuded, that it be carefully and systematically replanted.’

However, ten years later in March 1893, the Kew Bulletin mentions that the St Helena redwood is also ‘now almost extinct on the island’, noting that Morris, now assistant director of Kew, took seeds of the tree and it was grown in the Hill Garden in Jamaica.

From the 17th century onwards, St Helena’s native trees were felled for timber and fuel, and introduced species including flax and goats caused devastation to the local flora. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew has been involved in botanical activities on the island since the 18th century and its director Joseph Hooker called the island’s flora ‘a fragment from the wreck of an ancient world’. Kew’s archival materials show that there has long been awareness of the need to protect its native forests. Where once the main concerns were safeguarding rainfall and local resources, today forest management is an essential part of the larger collaborative fight against biodiversity loss and climate change.

Today, Kew’s UK Overseas Territories team works in partnership with international and local conservation organisations to help restore the flora of St Helena and bring its endemic species back from the brink. The St Helena Cloud Forest project is an important example of using nature-based solutions to meet the challenges of the 21st century. In its aim to conserve water supplies, the project displays the continuities in forest conservation from the 19th century to today.

See: https://www.sthelenatourism.com/st-helenas-cloud-forest-project/

https://www.sainthelena.gov.sh/2022/news/st-helena-cloud-forest-project-update/

19. Sketches of St Helena Dwarf Ebony

William Burchell (1781-1863)

Watercolour on paper sketch

The St Helena ebony, Trochetiopsis melanoxylon, was endemic to the island but became extinct around 1800, likely seen last by Sir Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander in 1771. The tree is closely related to T. ebenus, the dwarf ebony, which remains critically endangered, as well as the St Helena redwood (T. erythroxylon) which is extinct in the wild. Their strong similarities led to confusion around the naming of these three species in early accounts. Naturalist William John Burchell travelled to St Helena in 1805 and produced a series of sketches of its flora and fauna while working as the island naturalist and superintendent of the botanic garden. Burchell did distinguish between the St Helena ebony, which he considered to be extinct by this time, and the dwarf ebony, of which he produced these detailed sketches in May 1810.

20. St Helena Ebony, ‘Melhania Melanoxylon’ and notes

John Nugent Fitch (1840-1927)

From St. Helena: A physical, historical, and topographical description of the island, by John Charles Melliss. London: L. Reeve & Co., 1875

The ebony once formed a large proportion of the island’s vegetation,

but the introduction of goats and foreign plants to the island decimated both the ebony and the forests more widely. The three species are frequently confused and misidentified in early accounts. John Charles Melliss, a British naturalist born on St Helena, does not differentiate between the two ebony species in his history of the island, but states that he believes the St Helena ebony ‘to be now extinct.’ Petitions were made to the East India Company directors to remove the goats according to Mellis, but they were considered more valuable than the trees.

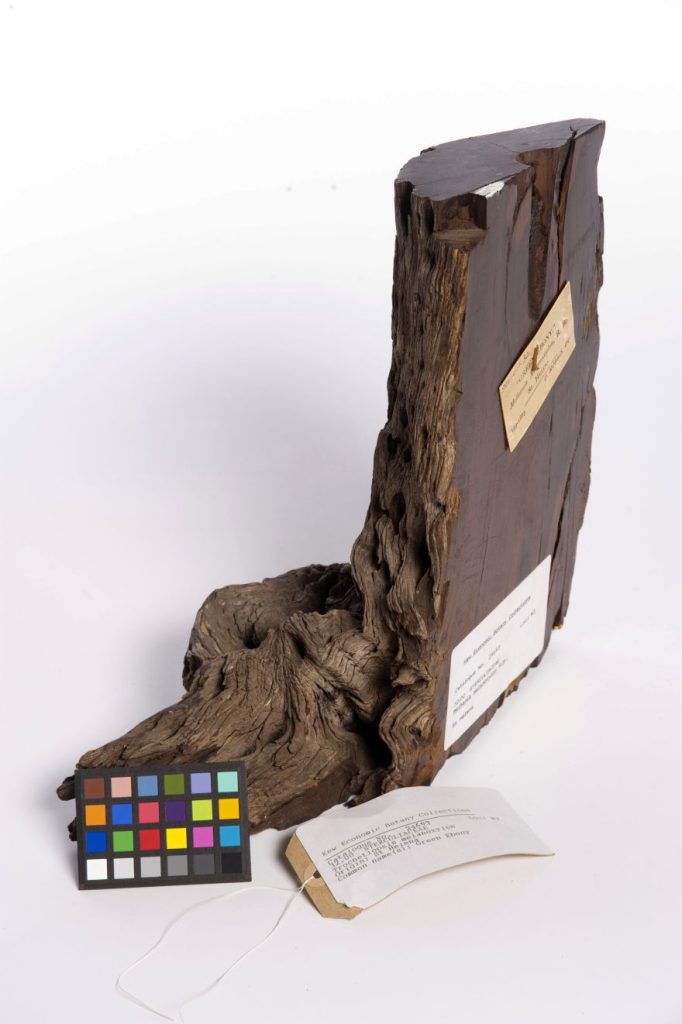

21. Wood sample of St Helena Ebony, 1883

Trochetiopsis melanoxylon

Economic Botany Collection, 24693

On his return from the island Morris supplied a sample of St Helena ebony (T. melanoxylon) to Kew, labelled as Melhania melanoxylon, shown here with an original label describing it as ‘Green Ebony’, seemingly to distinguish it from the St Helena redwood. Now held in the Economic Botany Collection, this strikingly large wood sample is an engaging memorial of this lost tree species. It is a symbol of the importance of forest conservation in preventing tree extinction.

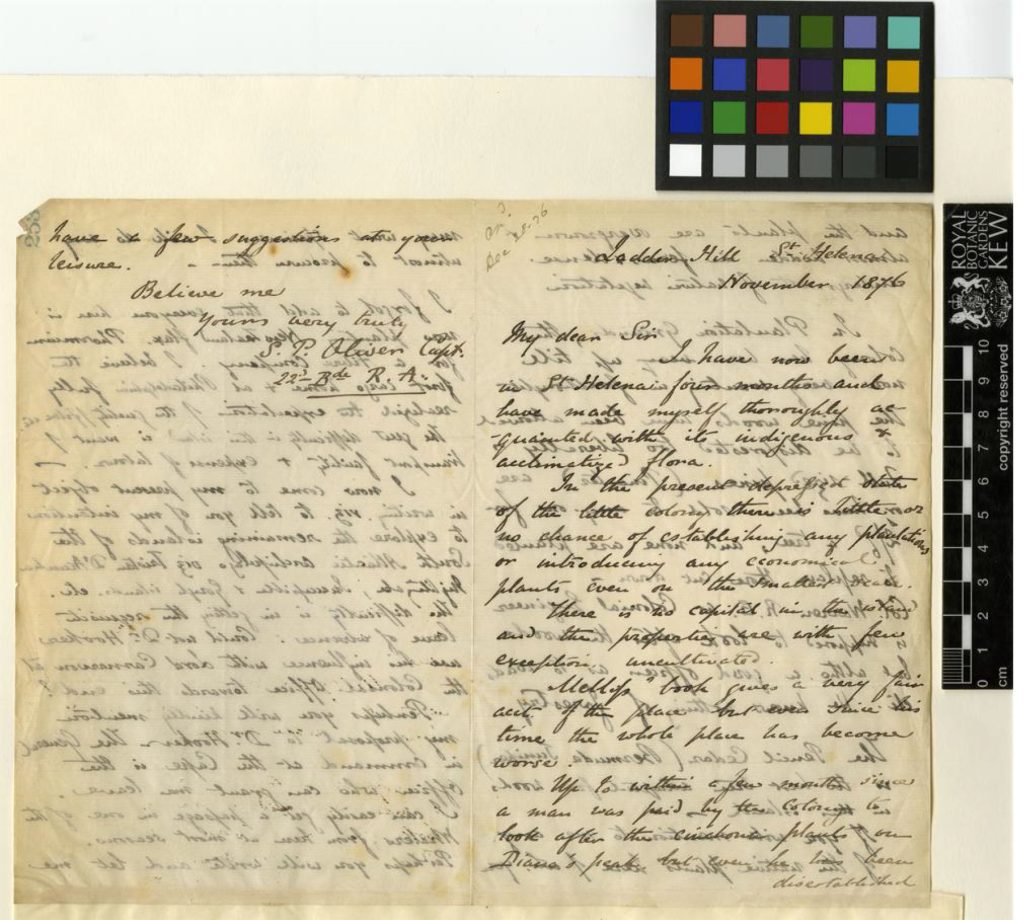

22. Letter from naturalist Captain S.P. Oliver to William Thiselton-Dyer, Nov. 1876

Directors Correspondence, DC/181/253.

Oliver tells Thiselton-Dyer there is little chance of establishing ‘plantations’ or introducing ‘economical plants’ but also talks about the deforestation of the island’s pine forests.

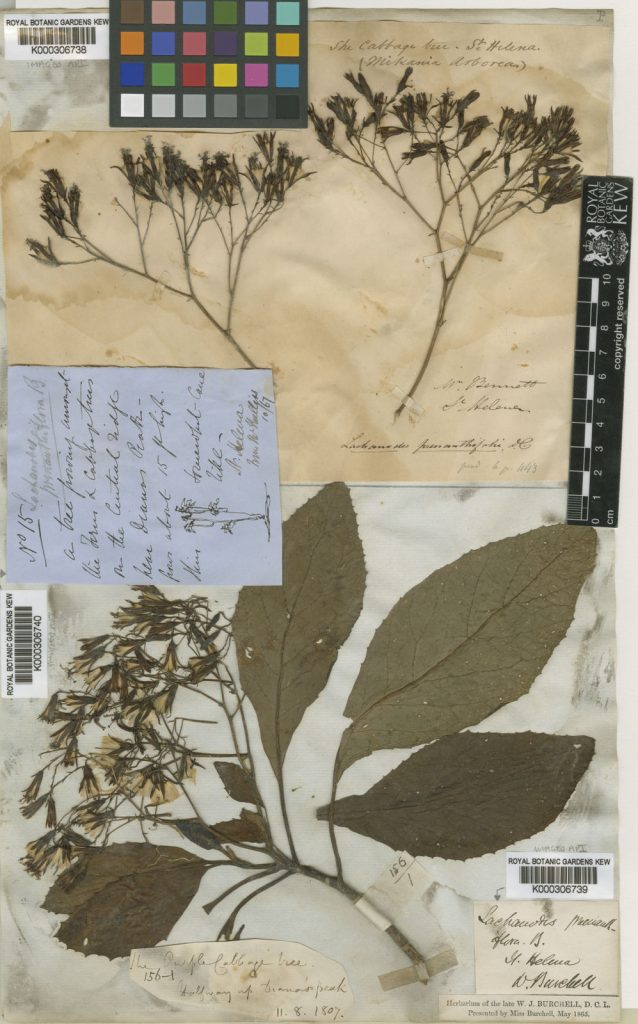

23. Kew herbarium specimen, she cabbage tree

(Lachanodes arborea), W.J. Burchell (1810). This specimen of an endemic species is a valuable record of the flora from the early 19th century.

24. Sketch of St Helena Gumwood, Commidendrum robustum, William Burchell (1781-1863). This endemic plant is critically endangered but was once one of the most abundant trees on the island. Burchell’s sketches in Kew’s Illustrations Collection are a vital record of the history of the island’s flora.

27. Report on a visit to St Helena

Miscellaneous Reports, St Helena: Miscellaneous, MCR/10/1, f. 22, 51-3

During an 1883 visit to St Helena, Daniel Morris, then director of the Jamaican Botanical Department (and later assistant director at Kew), recommended that the Central Ridge known as Diana’s Peak should become a ‘Belt of Forest land … which would materially increase the Rainfall.’ The map included in the report shows this ‘central zone’ of Diana’s Peak, where Morris notes ‘the climate is particularly cool, the sky being continually obscured by mist and cloud.’ Directly connecting forest conservation to levels of rainfall, Morris’s account connects 19th century botanical activities in St Helena to the current Cloud Forest Project, which aims to support water security and climate resilience by regenerating this area, now part of the Peaks National Park.

This is an example of how archival materials form an important part of the context for current Kew Science projects, displaying the long-term changes and continuities in Kew’s conservation activities.

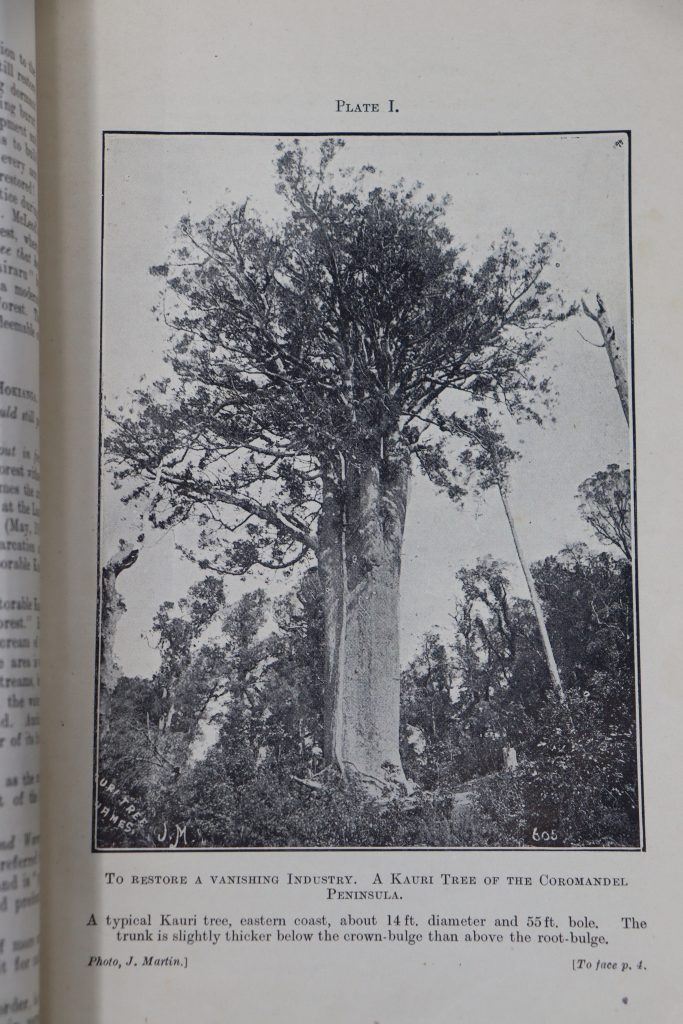

29. ‘Dammara australis’, Pinetum woburnense

James Forbes and John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford.

London: James Moyes. 1839

The kauri tree (Agathis australis, previously known as Dammara) only grows on the North Island of New Zealand. It is one of the most magnificent and important trees of that country, with some of the largest specimens (such as Tāne Mahuta) standing around 45m tall. Kauris are slow-growing and are said to live for over a thousand years. Their enormous, completely straight, ghostly-grey trunks create an imposing presence in the native forests.

The Māori consider kauri as sacred as they play an important part in their creation myth. They used them for building canoes (waka), housing, and creating cultural carvings. Kauri forests were already slowly diminishing through Māori uses and fire, but once they became known to Europeans in the 18th and 19th centuries the trees began to be extensively logged for their straight-grained, durable timber, harvested for their resin (known as ‘gum’), or removed to make way for the rapidly increasing settler population.

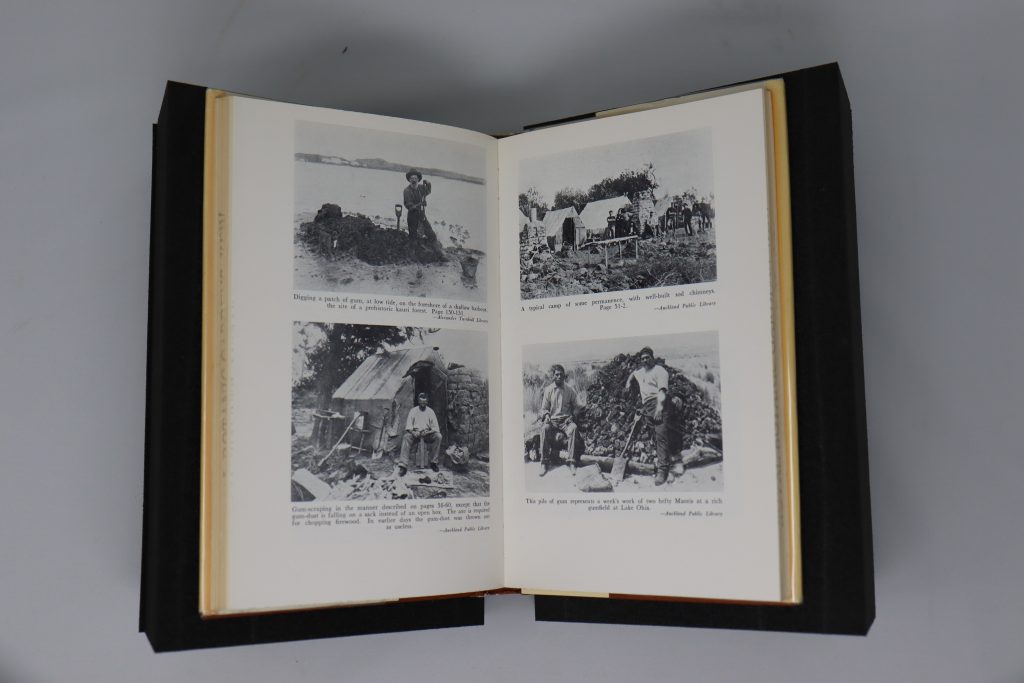

30. The Gumdiggers : the story of kauri gum

Alfred Hamish Reed

Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed. 1972

31. Kauri gum

Agathis australis

Economic Botany Collection, 31026

Kauri ‘gum’ is actually a resin that exudes from the tree and can be scraped fresh from the bark or collected by cutting a gash into the tree. The gum was also found to have semi-fossilised in the soil around the trees and could be dug out as ‘copals’. When demand for the gum vastly increased, deforested areas would be mined by ‘gum-diggers’ seeking this resinous substance. This occupation was said to be the salvation of many in times of hardship. In 1886, 1,230 people made their living by gum-digging. The gum (also known as dammara) was originally used for repairing the waterproofing of wooden ships, but in the 19th century became a valuable commercial ingredient used in the manufacture

of varnishes.

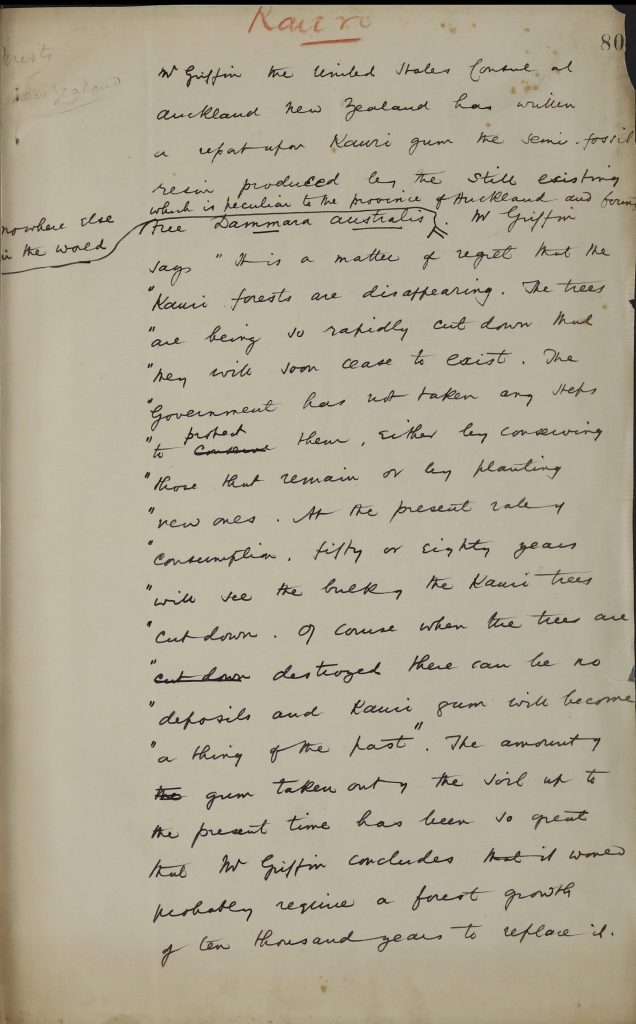

32. ‘Kauri’

G.W. Griffin

Miscellaneous Reports, New Zealand and Tasmania: Miscellaneous, MCR/8/1/1/80

So great was the demand for kauri timber and gum that reports began to circulate in the late 19th century that the forests would be totally destroyed in just a few decades if deforestation wasn’t controlled. Despite a New Zealand Forests Act in 1874 (influenced by both European and Indian forestry practices), and the creation of a state forest service, people began to be afraid of a ‘timber famine’ and were concerned about soil erosion and flooding, as noted here in quotes from a report by GW Griffin. However, this environmental anxiety did not immediately halt the deforestation of these ancient giants to make way for agriculture, housing and railways.

33. New Zealand Forestry: Kauri Forests. 1919

D.E. Hutchins

This report by ‘imperial forester’ Sir David Hutchins recognises the historical importance of the kauri tree as well as its present and future economic value. It also warns that the prospects of sustainable timber and gum industries were often being squandered through poor management of the forests. However, shifting public attitudes began to play a large part in greater forest and nature protection. Today, many recognise the ecological and cultural importance of the kauri. This parallels the growing Rights of Nature Movement that supports the legal rights of forests and ecosystems. In New Zealand this stems from the spiritual beliefs and cultural practices of the Māori, who believe elements of the natural world have their own life force (mauri).