Biscuit Town: 200 Years of Huntley & Palmers in Reading

If you think of famous biscuit manufacturers, which companies spring to mind? McVities, perhaps? Jacob’s? These names didn’t always dominate the market of dunkable delicacies. In the 19th century and for much of the 20th, Huntley & Palmers were the biggest global name in biscuits. Not only were they based in Reading, they shaped the growth and culture of the town. We are lucky enough to hold the company’s business archive, within the University of Reading’s Special Collections. Through this display we hope to show just how wide the impact of ‘Biscuit Town’ was.

This exhibition is part of a joint programme of events and activities celebrating 200 years of biscuit heritage at The MERL and Reading Museum, as part of Museums Partnership Reading, and funded by Arts Council England.

The Citizens of Biscuit Town

In 1894, around 9% of Reading’s population worked for Huntley & Palmers. It is therefore inevitable that the company touched the lives of a vast number of people. In fact, the building which is now our very own Museum of English Rural Life was once owned by Alfred Palmer, head of the engineering department.

Within this display, we want to focus on some of the personal stories linked to Huntley & Palmers. The exhibition focuses on various individuals, from unknown biscuit packers to famous champions of workers’ rights. We believe that everyone in Reading, and many beyond, has a link to the company. Perhaps you do too?

Credit line - George Palmer and staff (1872), HP 118

The birth of Biscuit Town

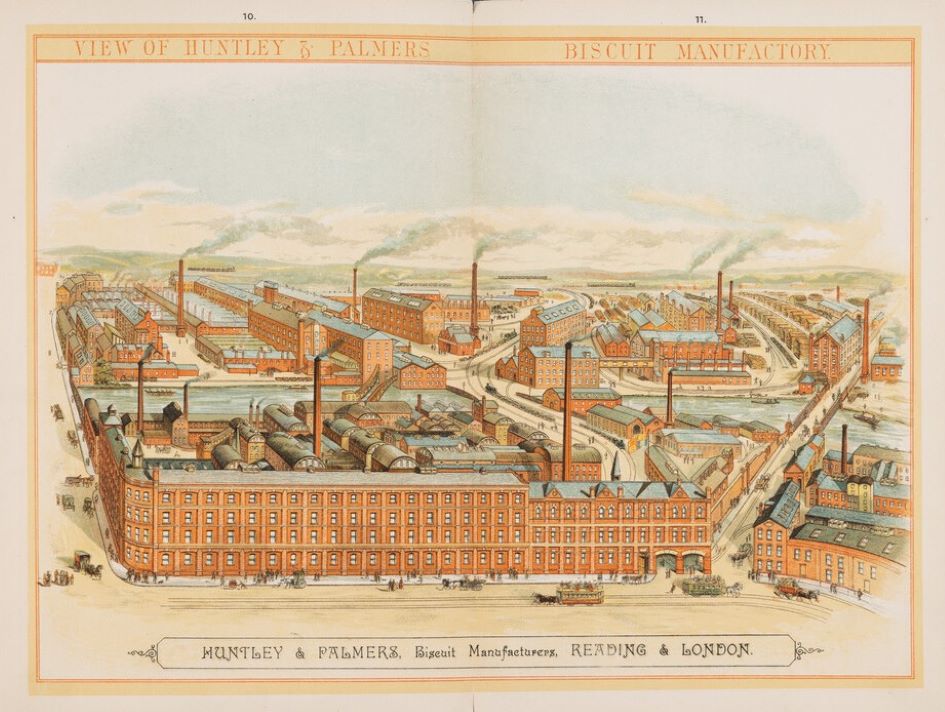

Huntley & Palmers has been intertwined with the culture, economy, and growth of Reading since the company opened a factory on King’s Road in 1846. As the factory expanded, working families flocked to the town to take up jobs in biscuit manufacture and distribution. As such, the town became synonymous with biscuit making, something the company encouraged and utilised in their advertising.

The cultural merging of town and company was demonstrated by Reading FC’s nickname of ‘Biscuit-men’, and Reading prison being known as ‘The Biscuit Factory’. Huntley & Palmers themselves frequently referred to Reading as ‘Biscuit Town’.

Credit line - HP 113

Henry Gibbs

Henry Gibbs is a good example of someone who took a risk and relocated to Reading in order to work for Huntley & Palmers. He was employed by the company in 1861, having recently moved from Oxfordshire. Aged only 14, he had no apparent connections to Reading and was lodging with the Day family.

Henry worked as a biscuit packer, a task typically performed by boys in the 1860s. We found Henry in the department’s wages ledger, and discovered he worked for Huntley & Palmers until at least 1866. He earned 16 shillings a week in 1863. This was around the average wage for an unskilled labourer at the time, which isn’t bad for a 16 year old!

Credit line - Biscuit packing department c.1900

Reading biscuits around the world

Huntley & Palmers became rapidly popular overseas, due to their innovative marketing strategies and the durability of their tins, which could keep biscuits fresh for months.

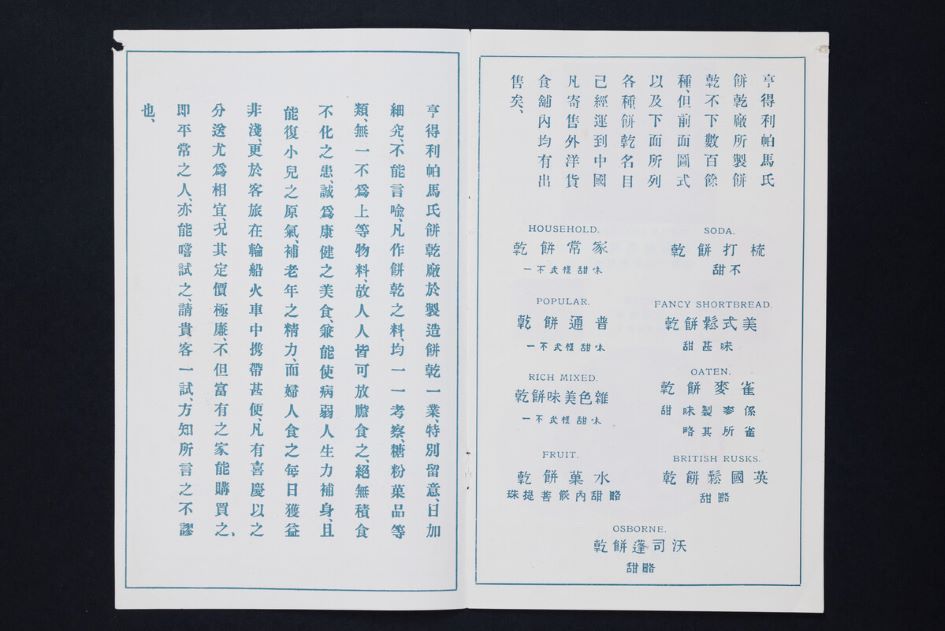

Advertising practice differed from country to country. For example, after the Qing dynasty ended in China in 1912, Western foods became fashionable and Huntley & Palmers biscuits were advertised as healthy, especially for babies and young children. Here we have an illustrated catalogue of biscuits written in Mandarin.

Credit line - HP 123

The unnamed Ugandan

Huntley & Palmers was a proprietor of commercial colonialism, exporting biscuits throughout the British Empire. Their products were usually targeted at the coloniser, not the colonised, offering a ‘taste of home’. Nonetheless, local people in colonised nations did interact with Huntley & Palmers products, particularly the tins. We know that in Uganda, locals used the tins to protect their bibles from white ants.

As is the case with many historical collections, the experience of the colonised does not feature

prominently the Huntley & Palmers archive. For example, workers who harvested coconuts in

Barbados for experimental biscuit recipes are not named. This makes their stories and experiences

even more valuable.

Credit line - MERL 2012/418

The 1912 protests

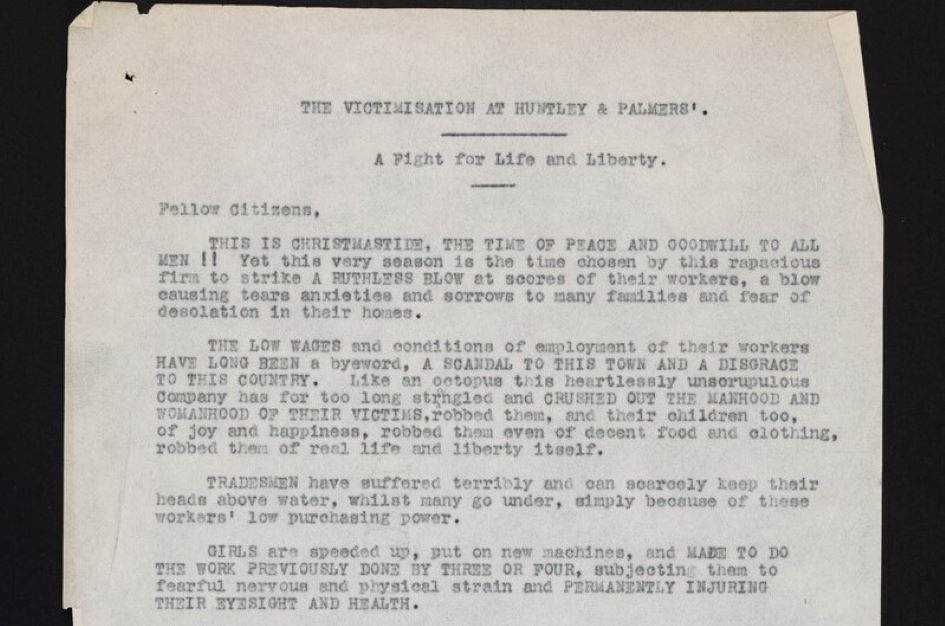

Despite donations towards the development of Reading, such as the opening of Palmer Park in 1891, Huntley & Palmers weren’t always so generous towards their employees. Stagnant wages were a major issue. Between 1889 and 1911, food prices in Reading increased 10% but wages did not rise at all.

Tensions came to a head in late 1911 and early 1912 when a number of women were unfairly dismissed. This resulted in a large demonstration of factory workers on 11th January 1912. Local papers estimated thousands of attendees. The unhappy protestors were determined to be a force for good as well as disruption; by the time of the gathering, they had raised £56 for

a Discharged Workers Fund.

Credit line - HP 89

Charlotte Despard

Suffragist and socialist Charlotte Despard was a key voice for workers’ rights during the 1912 protests. She spoke to a large crowd at Reading town hall, outraged by Huntley & Palmers refusal to negotiate with trade unions. She also rallied against poor working conditions, raising concerns about the safety of the new weighing machine.

The directors of Huntley & Palmers failed to cooperate, openly denying Despard’s accusations, as shown by publications sent to their staff. Resentment continued to simmer until further protests in 1916, which resulted in wage increases and establishment of a Workers’ Representation Committee.

Credit line - Image courtesy of LSE Women's Library

George Watson

We believe that much of Reading’s history has links to Huntley & Palmers, and the Museum of English Rural Life, where our collections are housed, is is no exception. The building was built in 1882 for Alfred Palmer, who worked for the company for 50 years. In 1911, the family allowed the University of Reading to take up use of the building as a hall of residence. Until this time it was known as East Thorpe.

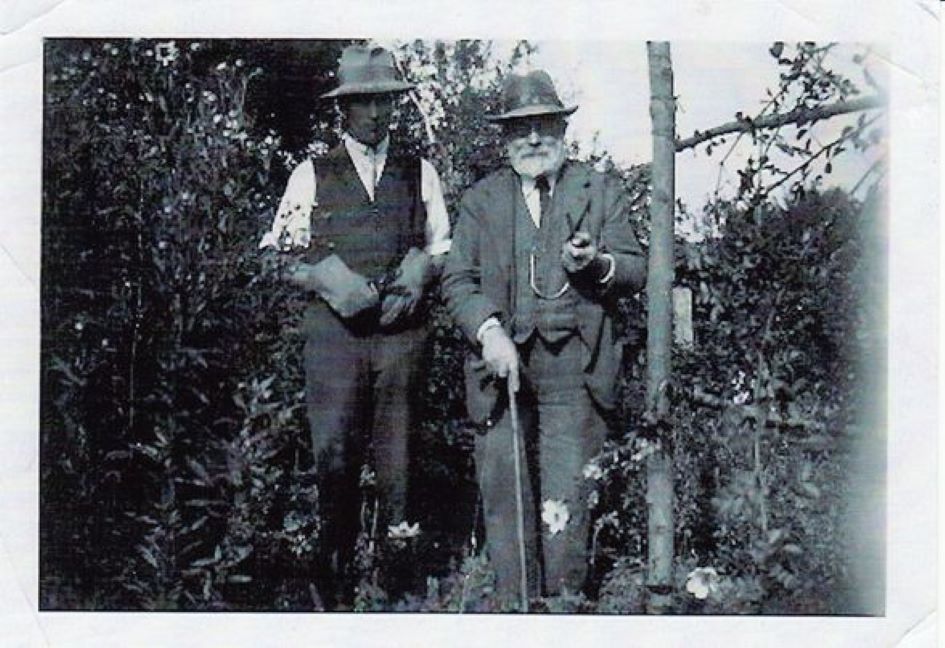

Upon East Thorpe’s completion, Palmer employed a gardener named George Watson. Born in 1850, George had previously worked at Upton Lodge in Old Alresford, Hampshire, before moving to Reading to start a family. In 1881 he was living at 61 De Beauvoir road, but by 1882 he lived and worked at East Thorpe with his wife Lucy and children Frederick and Ellen.

Credit line - Photograph courtesy of Jan Brown

Gardening for Alfred Palmer

George’s work would have included the familiar tasks of planting, watering, trimming, and weeding, as well as maintaining a greenhouse. The plants and earth in the garden today represent him, as they are the truest legacy of his work. The garden photograph you can see here was taken between 1880 and 1930.

George and his family probably would have lived in outbuildings which have since been replaced by the Museum’s galleries.

Many thanks to Jan Brown—George’s great-granddaughter—for her assistance with this research.

Credit line - MERL P DX322 PH1/DL/769

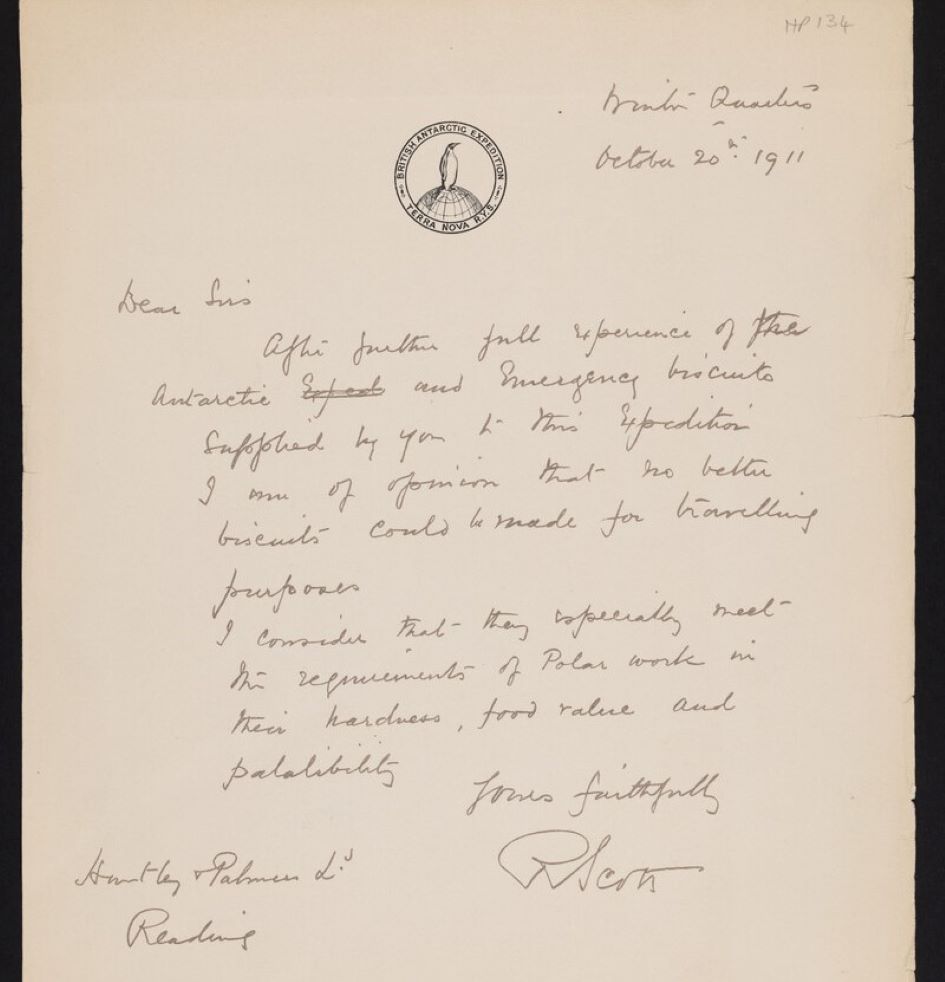

Captain Scott

The durability of Huntley & Palmers tins, and the longevity of their products, made the company popular with those travelling lands unknown to the British. An extreme example was Captain Scott, who took biscuits and cakes on his Antarctic expedition in 1910. The team’s goal was simple; to be the first to reach the South Pole. Scott wrote back to Huntley & Palmers a year later, praising the virtues of their products.

Credit line - HP 134

Biscuits in the ice

Tragically, Scott never returned from the Antarctic, having been beaten to the South Pole by the Norwegian Roald Amundsen. The biscuits remained, unused in the food depots the expedition established.

In 1956, Huntley & Palmers products were found and photographed in Scott’s camps, preserved by the frigid temperatures. More recently, the tins have been conserved in his hut on Cape Adare, and stand as a permanent reminder of Scott’s final journey. The artefacts within this hut include a 111-year-old fruit cake; upon finding it, conservators reported it smelled almost edible.

Credit line - HP 134

Ida Lindsay

Featured in the company’s internal journal, First Name News, Ida Lindsay worked for Huntley & Palmers for at least 40 years, starting her secretarial role in 1916 and continuing until 1956. Staff reaching these milestones often received commemorative gifts, such as watches and armchairs.

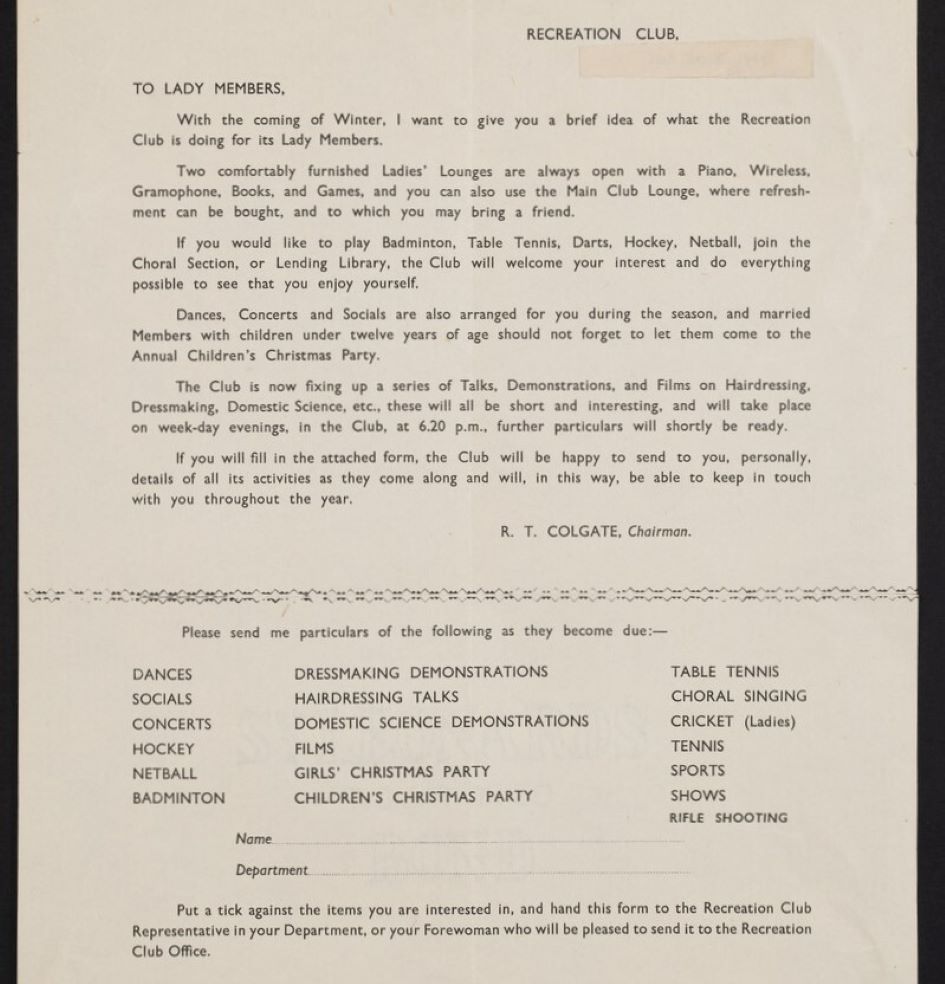

Ida was a keen participator in the company’s Recreation Club, being a talented tennis player. The Club was formed in 1899 and remained popular until biscuit production ceased in the 1970s. The sports on offer included football, cricket, bowls, tennis, and athletics. Ida may well have received this circular sent to female Club members. After the First World War, the Club branched out into horticulture and amateur dramatics. It was an essential part of life at Huntley & Palmers.

Credit line - HP 767

From factory to farm

Huntley & Palmers played an essential role during the Second World War. They provided rations for soldiers as well as new products ideal for rationing, such as ‘emergency bread’, which could last for up to ten years.

However, some women working in non-manufacturing roles were taken away from the company to work in the Women’s Land Army. This organisation enrolled women farmers to increase food production at a time when Britain had to be mostly self-sufficient. Ida was one of these women. She would have been trained to use farming equipment in a role vastly different to her secretarial work.

Credit line - P DX289 PH2/17/4871

The Wilde family

In June 1940, Reginald Wilde was working in Paris for the Huntley & Palmers Courneuve factory. This was the only factory the company ever opened on foreign soil. At this time, they had been requisitioned to produce rations for the French army. Reginald’s wife Dorothy

and their three children had been moved to the safety of La Baule, a town on the West Coast of France. Dorothy worked as an interpreter for injured British soldiers in a local hospital.

After the defeat of the French forces, Reginald was assigned the task of evacuating British staff and their families from France. However, he did not receive any resources or support from the directors of Huntley & Palmers back in England. He gathered the British staff and their families, and departed Paris in a convoy of cars, just days ahead of the German advance.

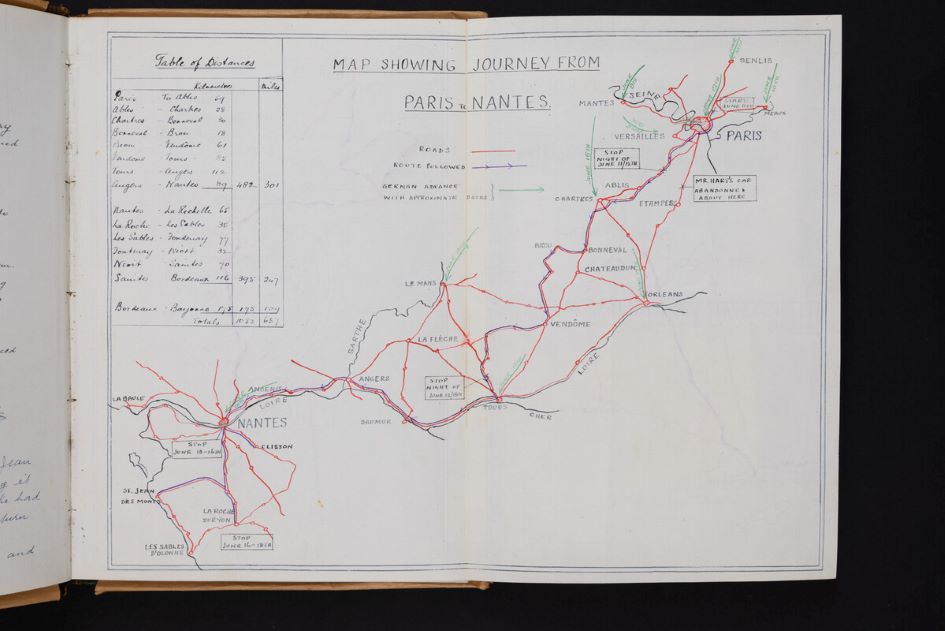

Credit line - Reginald's map of their journey, MS 5783

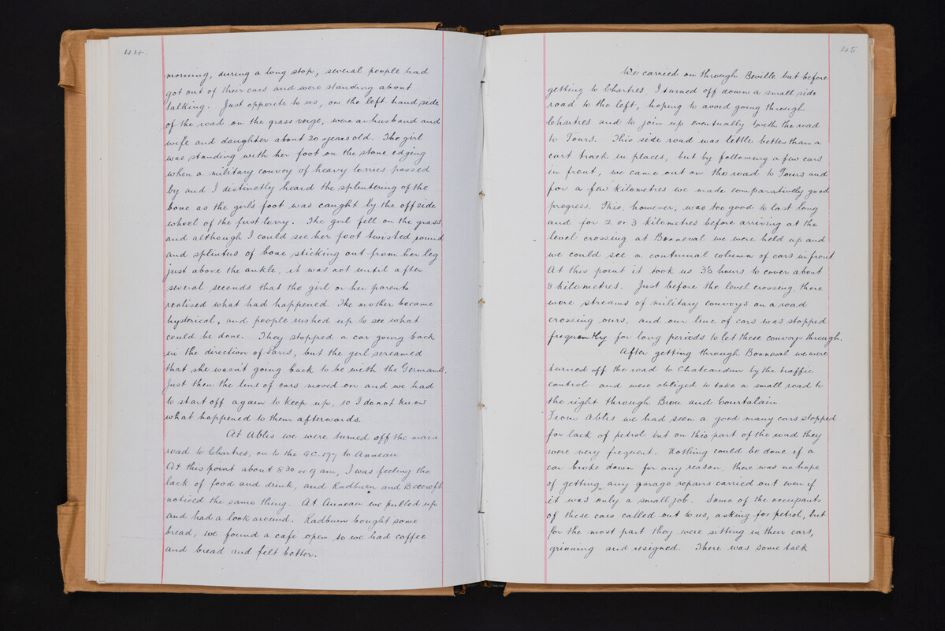

A narrow escape

The Huntley & Palmers convoy set off in the direction of La Boule, purchasing temporary accommodation along the way. They slept only a little, rising at 3:30am each day to continue their desperate journey. They were only ever a few days ahead of the Germans; on the night of

the 12th June they stopped near Tours, and the German forces swept through the same area on the 18th.

Dorothy, not knowing this, arranged passage to England on the Red Cross Ship RMS Lancastrian. Reginald and the convoy arrived just in time to prevent her getting on

board. This saved the lives of her and her children, as the ship was tragically sunk by the German navy.

The Wilde family, along with other Huntley & Palmers employees, gained passage on the Newhaven and arrived safely back in England on Sunday, 23rd June.

Credit line - Part of Reginald's account, MS 5783

Reading more, and using the archive

If you would like to read more about this exhibition, take a look at this blog which delves deeper into some of the stories we have touched on. Please note that the physical exhibition is no longer on display.

However, we would love for you to start your own journey with the Huntley & Palmers archive. If you would like to use anything from the archive, use this link to browse its content. We have also published advice on how best to use the archive to research family history. If you decide you would like to visit, email specialcollections@reading.ac.uk to get you started. We look forward to seeing you!

Credit line - Illustration of King's Road factory, HP 35