Nav

The First Treatise on Beekeeping

The very first treatise on beekeeping published in English was written by Thomas Hill in 1568.

Interestingly, Hill was not a beekeeper. His knowledge came entirely from what he had read in the fables of ancient writers, such as Virgil and Aristotle. Therefore, his description of the beehive was not entirely scientific.

He celebrated the hive for being clean and pious while the worker bees showed absolute ‘obedience to their king.’ In Hill’s opinion, beehives were a model society, and men would become more virtuous by tending to such moral insects.

Image: The title page of Thomas Hill’s A profitable instruction of the perfite ordering of bees (1579)

The Queen Bee: a new discovery

In 1609 Charles Butler revolutionised beekeeping by confirming the existence of the queen bee.

This was an important advancement as it implied that God had ordained female leadership. It was no coincidence that this discovery came soon after the reign of Elizabeth I.

While Butler derived most of his knowledge from observation, this did not stop him from making some outlandish claims. He asserted that bees were highly religious. In one instance, he described that they erected a chapel of wax when the host was placed in their hive, complete with working church bells.

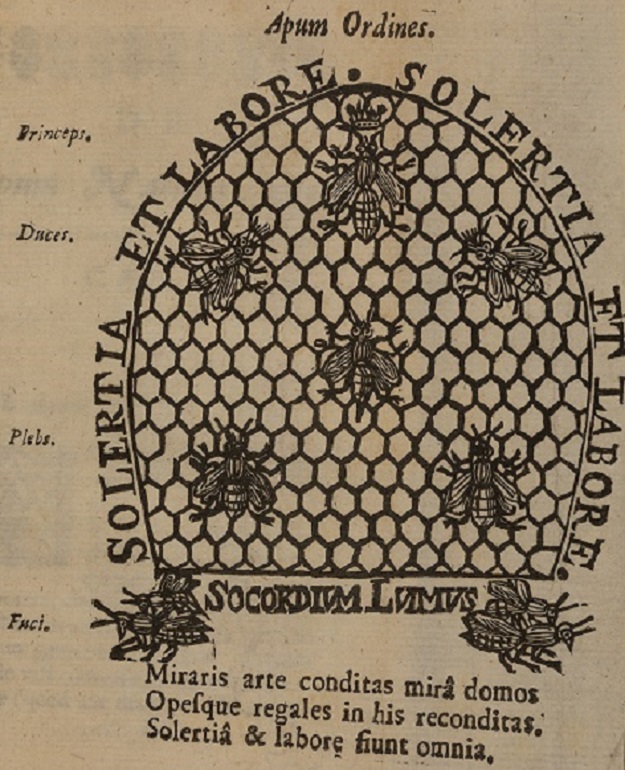

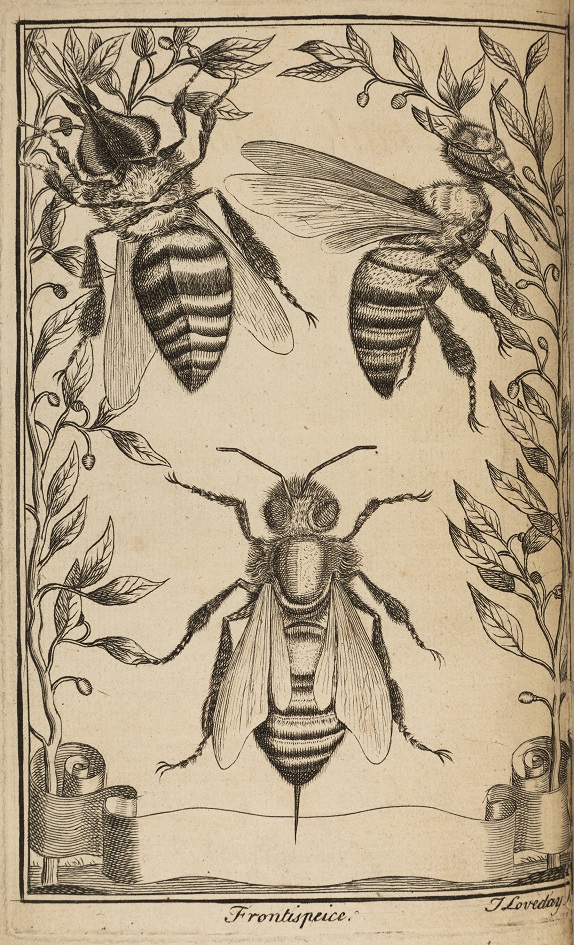

Image: Plate from Charles Butler’s Feminine Monarchie depicting the hierarchy of bees (1609)

The Ordering of the Beehive

However, after 1609 scholars did not immediately accept the queen bee into their writings.

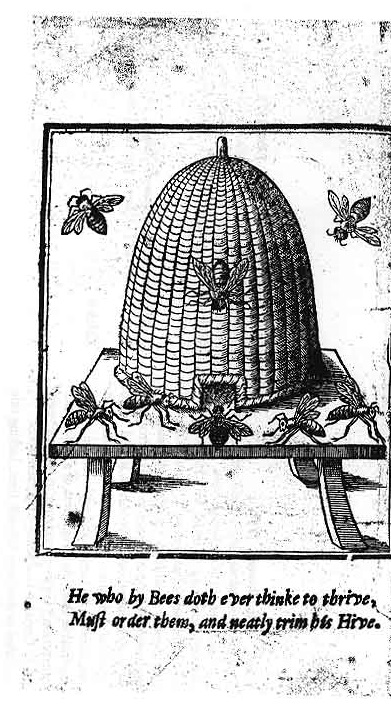

In 1634 John Levett wrote The Ordering of Bees. He argued that bees must be controlled by male master bees, and made many parallels between beehives and human society, especially in relation to punishment of the idle.

Levett made comical comparisons between drones – male bees – and lawyers, arguing that if both ‘exceeded due proportion’ they would destroy their respective commonwealths.

Image: Illustration of an ordered beehive taken from John Levett’s The Ordering of Bees, (1634)

Bees and the British Monarchy: The Hierarchy of Bees

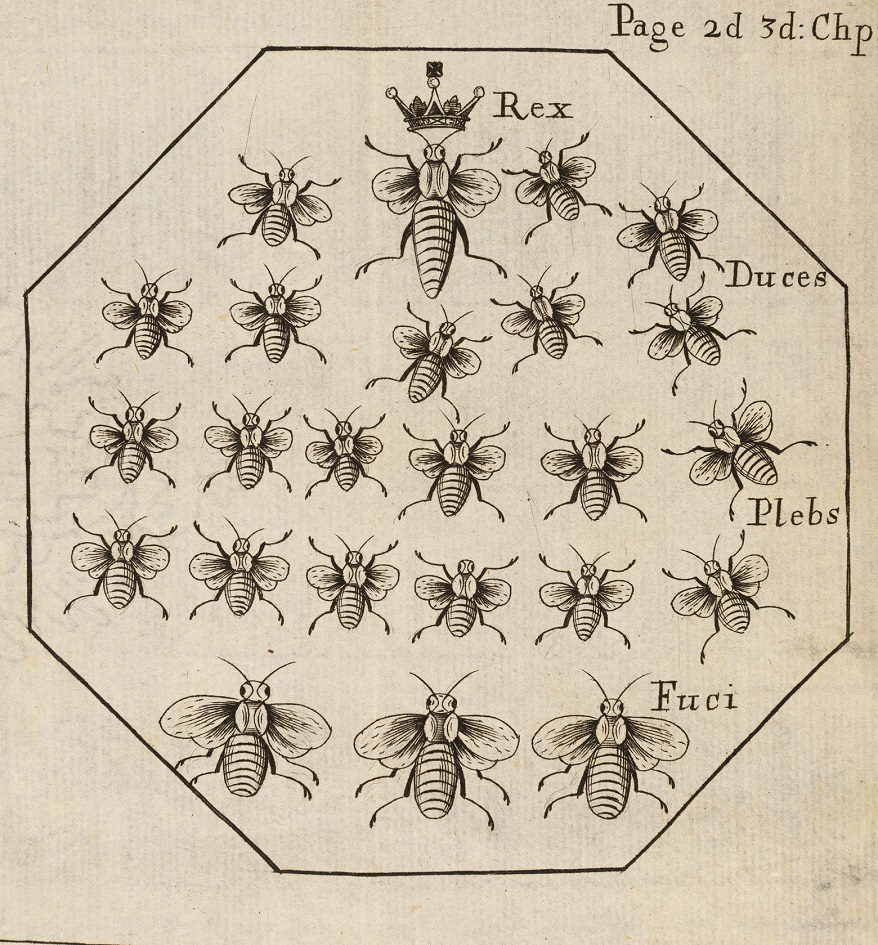

Some ignored the existence of the queen bee due to their own political agendas.

Moses Rusden, King Charles II’s official beekeeper, attempted to use the beehive to justify the divine right of kings in 1679.

He harked back to the language used by Thomas Hill, in the very first beekeeping treatise, by arguing that man and bee would both perish without royal leadership.

By placing his argument in the animal world, he emphasised that a class-based society was designed by God. By contrast, ‘rebellion and treason’ were utterly unnatural.

Image: A hierarchy of bees contained within a honeycomb, taken from Moses Rusden’s A Further Discovery of Bees (1679)

Bees and the British Monarchy: A Continued Justification

By the eighteenth century, scientific advancements meant that the queen bee’s existence could no longer be denied.

Instead, in 1716, Joseph Warder chose to highlight the importance of male drone bees.

However, he too used beehives to defend the role of the monarchy. After the success of the first edition, Warder dedicated his book The True Amazons to Anne, Queen of Great Britain.

Once again, bees were used to prove that ‘monarchy is founded in nature.’

Image: Portrait of John Warder from his 1716 book, The True Amazons, or the Monarchy of Bees.

The Domestication of the Beehive

As the concept of the queen bee was accepted, male scholars attempted to change the imagery surrounding the beehive.

In 1744, Presbytarian Reverend John Thorley wrote Melisselogia. He emphasised that a queen bee meant that the beehive was no longer a royal kingdom, but a domestic home.

Thorley believed that the queen bee served as a demonstration to women that it was their duty to ensure that they and their homes were chaste and clean.

Male drones, Thorley argued, were royal consorts and thus exempt from labour.

Image: Frontispiece of Melisselogia, or the Female Monarchy (1744)

Developments in Beekeeping: The Domestic Queen Bee

Imagery likening the beehive to a domestic home soon spread, even to scientific guides.

In 1780 John Keys wrote in his handbook The Practical Bee-Master that the queen bee is ‘the common mother’, rather than a regal figure, who should only be praised for her reproductive abilities, rather than her leadership.

However, even Keys used imagery of thrones and palaces when describing his domestic queen. Evidently the beehive retained some of its ancient splendour in the minds of scholars.

Image: Plate from The Practical Bee-Master depicting new advancements in beekeeping, (1780)

Developments in Beekeeping: Controlling the Queen Bee

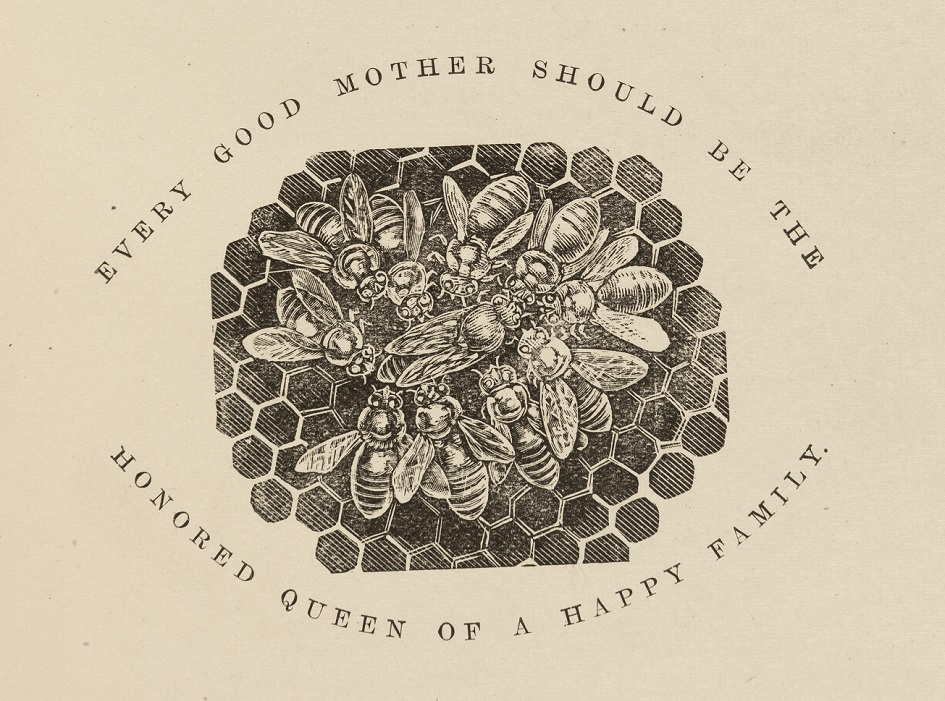

The symbol of the domestic hive continued well into the modern period.

This image featured on the title page of many editions of L. L. Langstroth’s A Practical Treatise on the Hive and Honeybee, first published in 1853.

Langstroth is commonly regarded to be the father of American bee-keeping and invented a ‘queen excluder’ to control the movements of the queen bee in the hive.

While the queen bee was still recognised as being vital to the survival of the hive, it was now beekeepers who controlled all aspects of hive life.

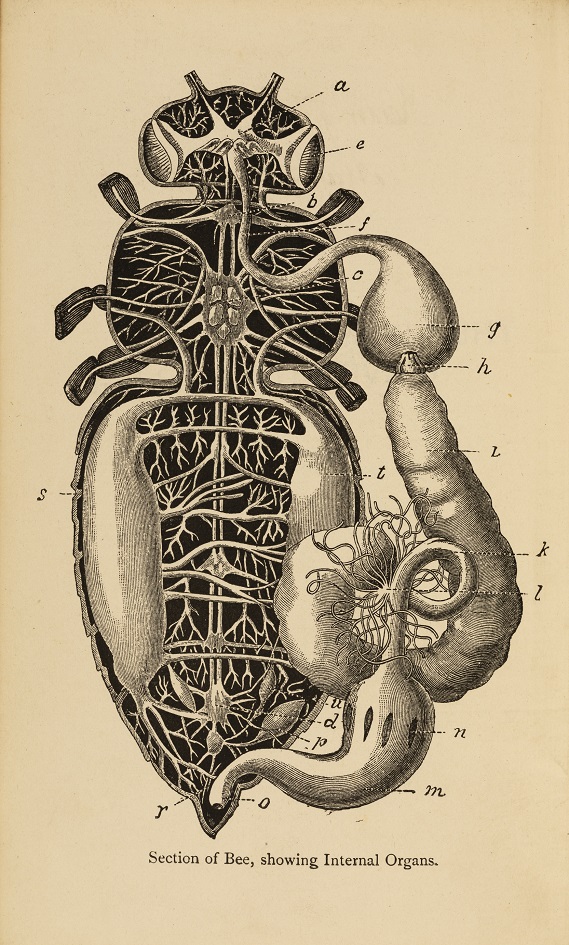

Bees in Science: The Anatomy of the Bee

It was in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that writings about beehives split into two genres.

Works by academics such as Thomas William Cowan painstakingly detailed the scientific aspects of hive life, while satirical publications likened beehives to British society in order to criticise the modern world.

Thomas William Cowan was President of the British Beekeepers Association, and accumulated one of the largest collections of books on bees. His work was vital to the shaping of modern beekeeping practices.

This diagram, from Cowan’s book The Honey Bee, first published in 1890, depicts the anatomy and organs of the honey bee.

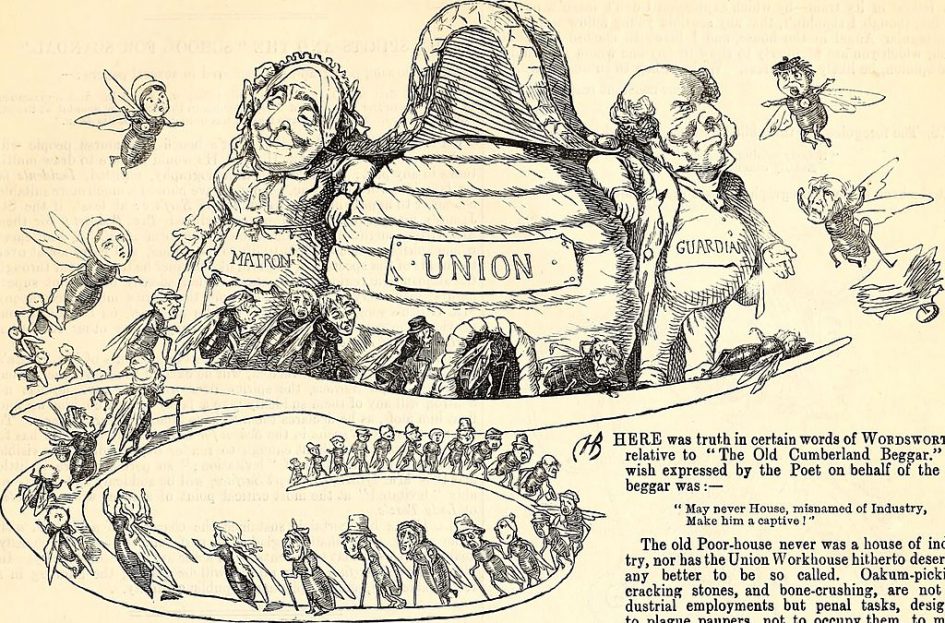

Beehives in Satire: The Natural Beehive

One of the most well-known users of satire was Punch, the weekly magazine.

They often comically likened working men to working bees and criticised their exploitation by the upper classes.

Honey and money were frequently compared as taxes on bees and man respectively.

This illustration was published in 1866 and described the beehive in similar terms to earlier writers such as Thomas Hill. This natural beehive represented an ideal workhouse in society. The poor would be cared for and efficiently employed in meaningful work.

Again, at least in satire, the natural beehive came to represent utopic ideals in society.

Image: Cartoon of a beehive representing a ‘model union workhouse’ from Punch, Saturday, June 23, 1866, Volume 50.

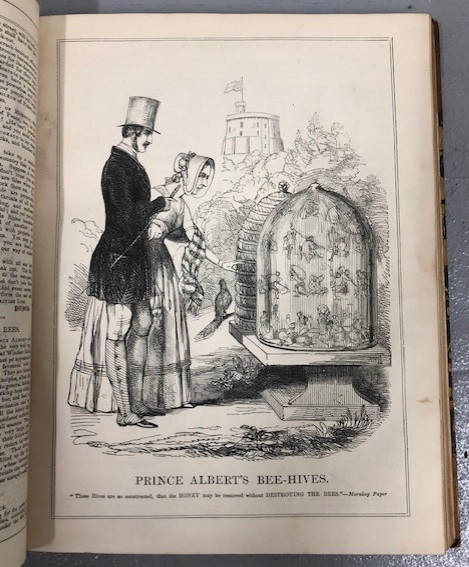

Beehives in Satire: The Man-made Beehive

Punch did not always depict beehives in such a favourable light.

In this cartoon from 1844, Prince Albert and Queen Victoria observe a glass beehive filled with labouring men and women trapped on different levels.

This man-made beehive was used to represent the exploitation of the lower classes in Victorian society and their inability to rise above their stations. Such rigid hierarchies were echoed in bee-hives.

Here, unnatural, man-made beehives became a symbol of the exploitation of the poor, unlike the natural beehive which represented an ideal and fair society.

Image: ‘Prince Albert’s Bee-hives’, a cartoon from Punch magazine, Saturday, Aug. 24, 1844, Volume 7, Issue Number 163.

Beehives in India: Justifications for Colonialism

Beehives were not only used to represent British society, but also the societies controlled by the British Empire.

In 1884, J. C. Douglas wrote about beekeeping in India. He argued that existing beekeeping methods were primitive and ‘barbarous’.

Europeans would have to lead the development of beekeeping, This justification for colonisation was based on the fact that natural bee-hives in India were seen as primitive and wild.

Evidently, the natural beehive did not always represent an ideal society. Beyond Britain, they were depicted as uncontrolled and used to justify colonial expansion.

Image: The front cover of J. C. Douglas’ A Hand-book of Bee-keeping for India. (Calcutta, 1884).

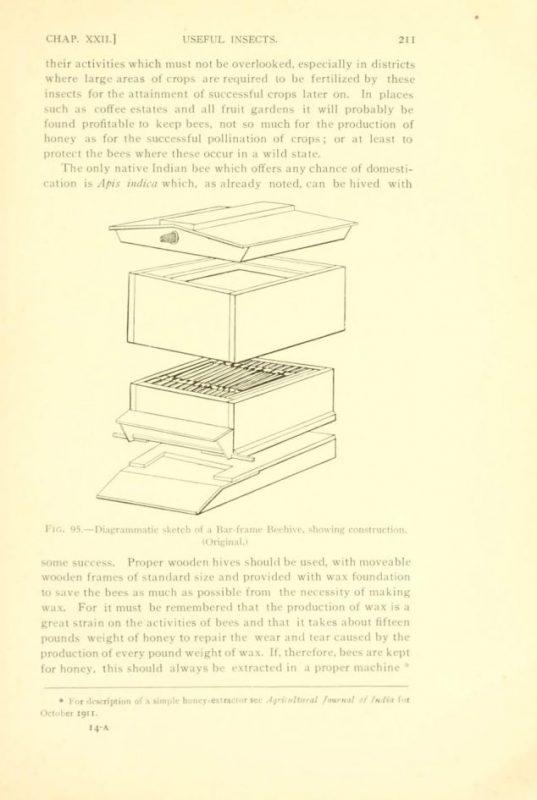

Beehives in India: Bees and Empire

Some colonial officials even used bees to justify their pseudo-scientific racism.

Thomas Bainbrigge Fletcher was an Imperial Entomologist for the British Empire and argued that Indian bees must be domesticated for the success of the beekeeping industry, in man-made hives like the one illustrated.

He argued that ‘the skin of low caste’ Indians did not seem to experience the sting of bees like the British did.

By making this comparison, he implied that Indian people were biologically different to the British and therefore inferior. The lack of man-made, developed hives in India supposedly supported his argument.

Image: A diagram illustrating a hive designed to domesticate bees in India, from Thomas Bainbrigge Fletcher’s Some South Indian Insects and Other Animals, (1914).