Biafra, the Nigerian Civil War and context in the archives (2/3)

This is the second of three posts in a series written by Temiloluwa Odugbesan, who completed a UROP placement at the University of Reading Special Collections in the summer of 2021.

Welcome to the second of my blog posts written during my UROP internship.

I have been tracing correspondence specifically relating to the Nigerian Civil War within Heinemann’s publications in the African Writers Series. During my time in the Special Collections reading room, I discovered how significant it is for my readers and myself to understand the context when approaching the material in the archives. The historical context sets the foundation for truly understanding the correspondence between Heinemann’s Nigerian and English offices, and enables us to be aware of possible biases in the material. It also helps us to interpret some of the more subtle references to events.

The Nigerian Civil War (also known as the Nigerian-Biafran War or the Biafran War) lasted three years and is thought to have led to 500,000 casualties and 2 million deaths from starvation. As well as its importance for understanding the material in the archives, the tensions that exploded during the civil war are still present, if somewhat dormant, in modern-day Nigeria. There remains a threat to national unity because there is still a desire for a resurrection of secessionist Biafra on the part of some Igbos, whilst others disagree.

Firstly, it is crucial to know that Nigeria, a country located in West Africa, is extremely diverse, home to over 300 different ethnic groups (see map below).

Map courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. [1]

In summary, the largest ethnic groups are the Hausa – Fulani who are situated in the North, Igbo in the Southeast, and Yoruba, in the West. After independence, the country was organised politically to maintain a very fragile balance of power between these main ethnic groups. As a result of varying beliefs, socio-political tensions, and lack of a sense of nationhood due to gaining independence only as recently as 1960 from the British Empire, many say this foreshadowed the outbreak of the civil war. As reiterated by Obafemi Awolowo “The word Nigeria was merely a distinctive appellation to distinguish those who lived within the boundaries of Nigeria from those who did not.”[2]

Furthermore, ‘An Igbo proverb’, retold by Chinua Achebe (the first author to publish his work, Things Fall Apart, in the African Writers Series) ‘tells us that a man who does not know where the rain began to beat him cannot say where he dried his body.’[3] So, let us explore the catalyst which brought about the Biafran War.

It is widely held that the chaos in the Western Region of Nigeria that resulted from the way the 1965 elections were conducted was a significant factor leading to the first military coup in 1966, and ultimately to the declaration of the civil war.

In 1959, Samuel Ladoka Akintola, the deputy leader of the Western Region’s Action Group (AG) political party, had become Premier of the Western Region. Serious disagreements between Akintola and Obafemi Awolowo (founder of the AG) led to requests by Awolowo’s supporters for Akintola’s replacement as premier in 1962. However, Akintola refused to resign, and his ability to remain in power was achieved by detaining Awolowo and imprisoning him. This signified that Akintola could rig the 1965 election in his favour. [4]

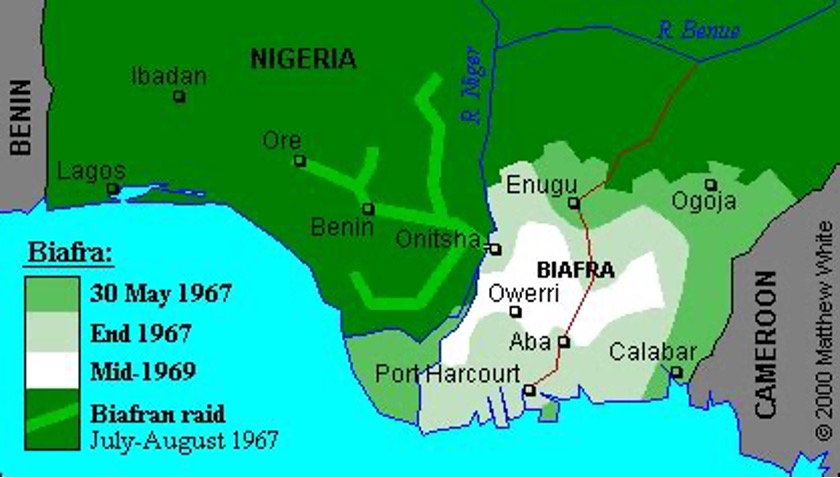

Seizing this opportunity, Akintola developed alliances with the political parties in the North, which then shifted the balance of power in the Republic such that the Igbos in the East were at a disadvantage whilst Akintola and the new party that he formed were able to achieve increased dominance in the North and West. Meanwhile, Igbos in the Northern region were subjected to ethnic cleansing and fled to the East. In a cry for help, the Igbo leader, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, submitted a request to government to create their own state, but this was rejected. As a result of the inaction against the ethnic cleansing of the Igbos, Ojukwu then declared secession, thereby bringing into existence the Republic of Biafra (see map below).

Copyright: Matthew White 2000 [4]

Why were Igbos targeted or others may say massacred?

The celebratory mood of the Igbos following the coup against the Hausa politician, Tafawa Balewa (Deputy Leader of Northern People’s Congress party) made it appear as though the Igbo people had all planned to target the Hausa in the North. This was especially the case as the assassination of Tafawa Balewa was successful; he died of an asthma attack whilst in custody under the military coup. Additionally, a second Hausa statesman, Ahmadu Bello, was also assassinated.

In other words, because the coup was led by an Igbo senior military officer and as a result an Igbo man became head of state, many were convinced this was the prelude to an attack on the Hausa population more broadly and many Hausa people felt deep distrust of Igbos because of what appeared to be the targeting of Northern leaders for assassination during the coup.

How were the British involved?

According to the historian G.N. Uzoigwe, Harold Wilson, the British prime minister during the 1960s and 70s, “blamed the crisis on Ojukwu, including the starvation in Biafra … He rejected outright the accusation that some Britons in Northern Nigeria encouraged the 1966 massacres, continued to supply necessary arms to Nigeria and supported total embargo of such supplies to Biafra. These policies were considered necessary to expedite the fall of Biafra and to save lives.” [5]

This was because, post-independence, it was in the economic interest of the British for Nigeria to stay as one country because of previously signed contracts concerning bi-lateral trade between Britain and Nigeria, in particular due to the discovery of oil in the Biafran region.

I hope this will give us greater understanding of how the Nigerian-Biafran war has influenced many literary works of the African Writers Series. The Series includes many texts about the civil war, such as Cyprian Ekwensi’s post-civil war novel, Survive the Peace (1976); I.N.C. Aniebo’s The Anonymity of Sacrifice (1974) and Christopher Okigbo’s poetry collection relating to the war, Path of Thunder (1971), to name but a few. Special Collections holds papers relating to all of these publications. Most of the books about the civil war published in the African Writers Series were from an Igbo perspective as Heinemann had found very few authors in the North to publish. However, the series does include Elechi Amadi’s memoir of fighting on the side of the Federal troops, Sunset in Biafra (1973) and one book written by one of the Federal side’s top commanders: General Olusegun Obasanjo’s My Command (1981).

References:

[1] Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin Nigeria / Central Intelligence Agency. The Agency, 1979. https://search.lib.utexas.edu/permalink/01UTAU_INST/9e1640/alma991049982299706011

[3] Chinua Achebe, There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra (New York: Penguin, 2012), p. 1; also quoted in G.N. Uzoigwe, ‘Background to the Nigerian Civil War’, in Falola and Ezekwem (eds.), Writing the Nigeria-Biafra War.

[4] Copyright Matthew White http://users.rcn.com/mwhite28/biafra.htm