‘Embellish’d With Gold’: Crafting an Online Exhibition of Premodern European Manuscripts

Blog post written and online exhibition curated by Joanna Hulin, Reading Room Assistant.

The European Manuscripts Collection held at the University of Reading’s Special Collections currently amounts to 143 items in total. When planning for the digital version of ‘Embellish’d With Gold’, I had thought that choosing just 15 items from the original 29 shown in our 2019 staircase hall exhibition would have been a fairly simple task. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

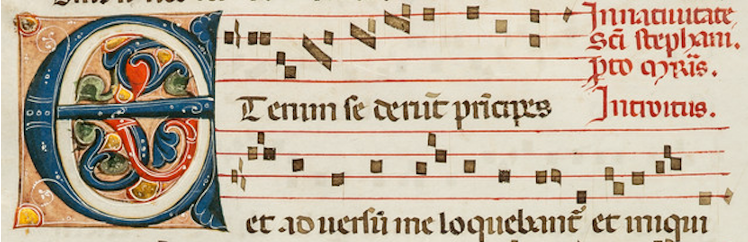

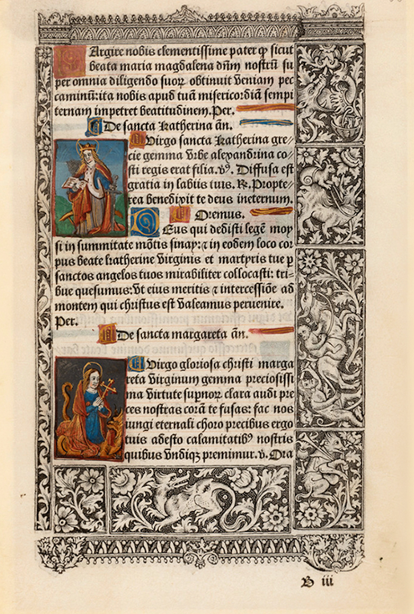

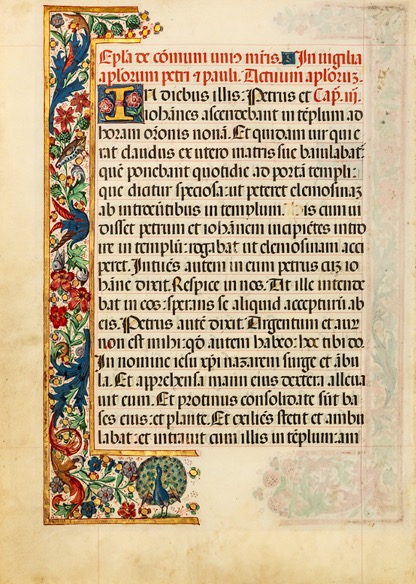

The beauty of manuscripts is that as they are crafted by hand, no two are ever exactly the same. Each one provides us with a unique insight into not only the historical context and societal attitudes of the time, but upon closer inspection it can give us information on the people who made the manuscript, as well as who it may have been made for. Given this wide variety of potential subject matter, it made selecting even a small handful of these pieces incredibly difficult.

Digital exhibitions are a relatively recent addition to the ways in which museums display and promote their collections, and during the COVID-19 lockdown they have become essential in helping to maintain a connection between cultural institutions and their visitors. They allow access to content from the safety of your own bedroom, and can give viewers a good idea of the scope and depth of an institution’s collection. And, in my case, they are particularly practical because you can create one from home if you have the right material.

They can also give rise to problems that are unlikely to be encountered when curating a physical exhibition. During my planning stages I was restricted in my choices by the fact that viewers are not able to walk around in a physical space, and are unable to see items up close or get an idea of how the objects might interact with one another. This can sometimes create limitations on how the material is perceived, particularly in terms of their ‘intended order’, and when thinking in a digital sense it usually calls for a more linear, narrative-led approach that has a clearer beginning and end. So, what aspects were the most important to consider when thinking about the narrative for this exhibition?

As the material in our collection spans across almost five centuries’ worth of history, I firstly wanted to reflect how manuscripts changed and evolved throughout this time period. With the introduction of the printing press in around 1455, and therefore the gradual shift away from handwritten texts, it felt appropriate to end the exhibition with a leaf from a book of hours printed by Antoine Vérard in 1506.

It was equally important to give an idea of the geographical scope of the collection, and how styles of illumination may have differed due to this. For example, how would a book of hours made in Belgium in the 15th century perhaps compare to one made in England from the same time period?

I also wanted to try and answer the questions of how these particular pieces in our collection were created and used in daily life. Each manuscript has its own story to tell, and I felt it was necessary to give all of them the time and breathing space they deserved in order to let viewers form their own responses to the material.

That being said, I should probably admit that some of them I put in simply because I liked the way they looked – as evidenced by the following note I made on one of my draft slides:

Another difficulty that can come up is having the ‘right’ amount of content. An exhibition can be as much about what you don’t include as well as what you do, and in this case there were many notes I had to omit either because they weren’t necessarily relevant to the item, or simply due to time and space restrictions. As I’d hate for them to go to waste, I have listed some articles below should you find them as interesting as I did – the British Library’s article on cat pawprints is a personal favourite.

Though I’ve spent a lot of time talking about some of the hurdles that came up when curating this exhibition, it’s truly been a delight to be able to work with them more closely in order to share more about our collection with you all. I have been lucky enough to handle some of these in person during my time working with the University of Reading, and I can say that they really are just as spectacular in real life.

Finally, through working on ‘Embellish’d With Gold’, it’s clear to me that whether they are intended for a layman learning to read, or a duke showing off his wealth, there is no doubt that these manuscripts hold an immense amount of cultural and historical significance. Practical functions aside, they are an astonishing display of craftsmanship and there are still many mysteries hidden within them waiting to be solved – even if they do end up being the handiwork of a rebellious cat. I will leave you with the hope that even though this year has brought some unexpected turns for us all, our collection of illuminated manuscripts have brought just that little bit more light into your day.

More information about the European Manuscripts Collection can be found on our A-Z pages, and a small selection of references have been posted below for your reading pleasure.

References

University of Reading Special Collections, ‘European Manuscripts Collection’. MS 5650. [https://collections.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/collections/european-manuscripts-collection/] Accessed 03/06/2020.

Khan Academy, ‘What is an illuminated manuscript?’ (2014). [https://www.khanacademy.org/partner-content/getty-museum/types-of-art/getty-manuscripts/a/what-is-an-illuminated-manuscript] Accessed 03/06/2020.

British Library Blog, ‘Bringing our medieval manuscripts to life’. [https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/index.html] Accessed 03/06/2020.

The Fitzwilliam Museum, ‘Illuminated Manuscripts in the Making’. [https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated] Accessed 03/06/2020.

Yale University Libraries, ‘Travelling Scriptorium: A Teaching Kit by the University of Yale Library’. [https://travelingscriptorium.library.yale.edu/] Accessed 03/06/2020.

Articles

Sarah Zhang, ‘Why a Medieval Woman Had Lapis Lazuli Hidden in Her Teeth: An analysis of dental plaque illuminates the forgotten history of female scribes’. The Atlantic (09/01/2020). [https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/01/the-woman-with-lapis-lazuli-in-her-teeth/579760/] Accessed 03/06/2020.

Colin Schultz, ‘Why Were Medieval Knights Always Fighting Snails?’: It’s a common scene in medieval marginalia. But what does it mean?’. Smithsonian Magazine (14/10/2020).[https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-were-medieval-knights-always-fighting-snails-1728888/] Accessed 03/06/2020.

Maria Popova, ‘Oh, My Hand: Complaints Medieval Monks Scibbled in the Margins of Illuminated Manuscripts’. Brain Pickings. [https://www.brainpickings.org/2012/03/21/monk-complaints-manuscripts/] Accessed 21/03/2020.

Eleanor Jackson & Kate Thomas, ‘Cats, get off the page’. Medieval manuscripts blog. British Library. [https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2018/12/cats-get-off-the-page.html?_ga=2.48744612.308638926.1552464787-989836958.1446713674] Accessed 21/03/2020.

Elizabeth Morrison, ‘Beastly tales from the medieval bestiary’. Medieval England and France, 700-1200. British Library Blogs. [https://www.bl.uk/medieval-english-french-manuscripts/articles/beastly-tales-from-the-medieval-bestiary] Accessed 21/03/2020.